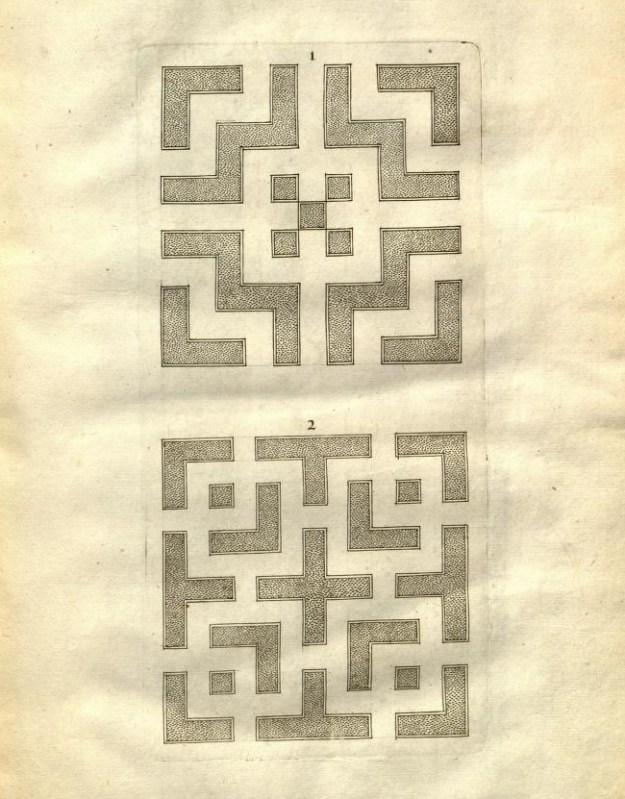

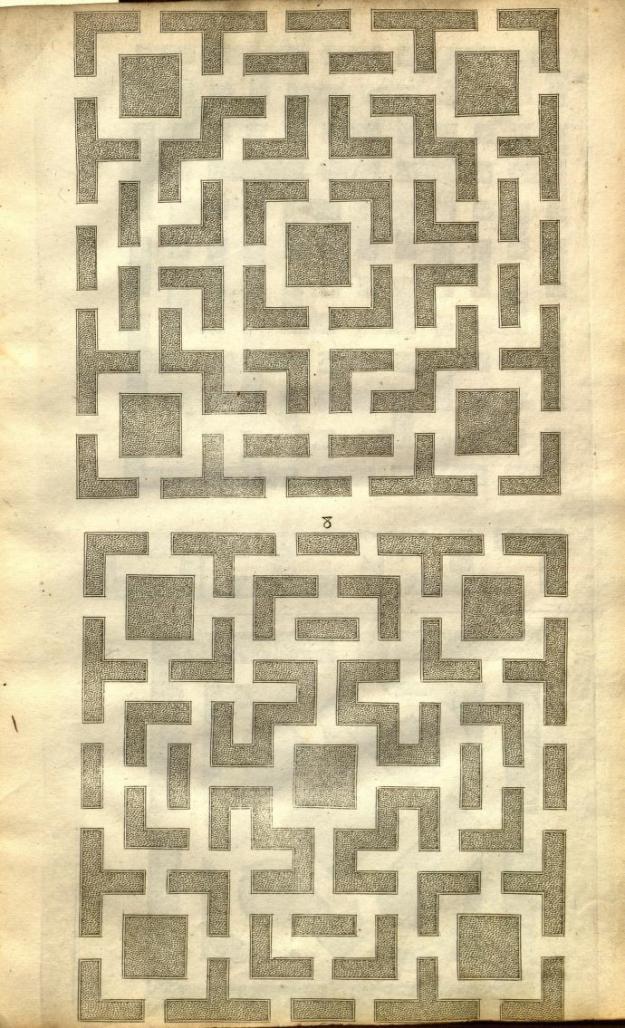

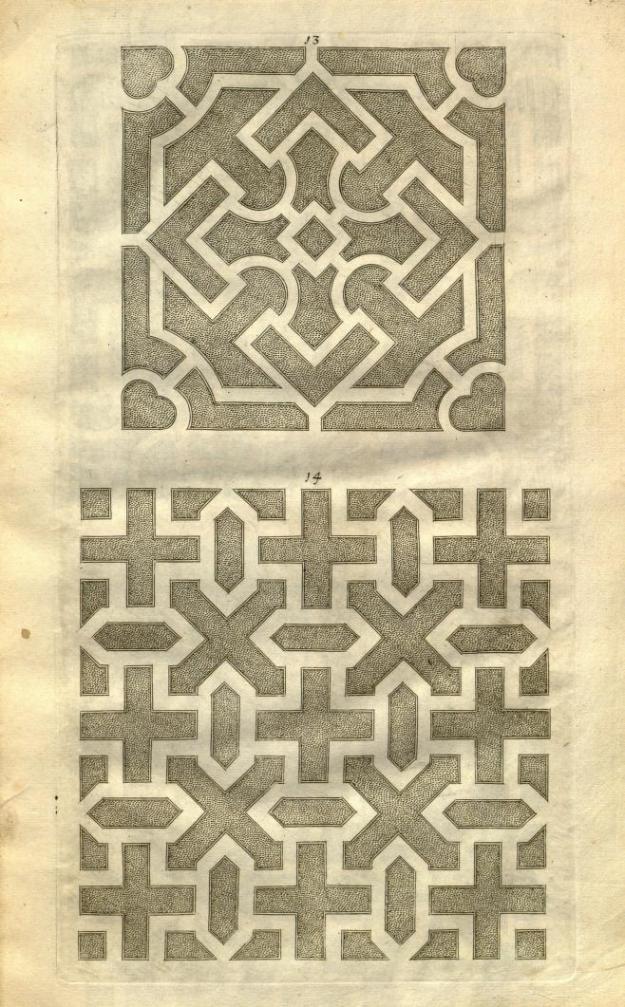

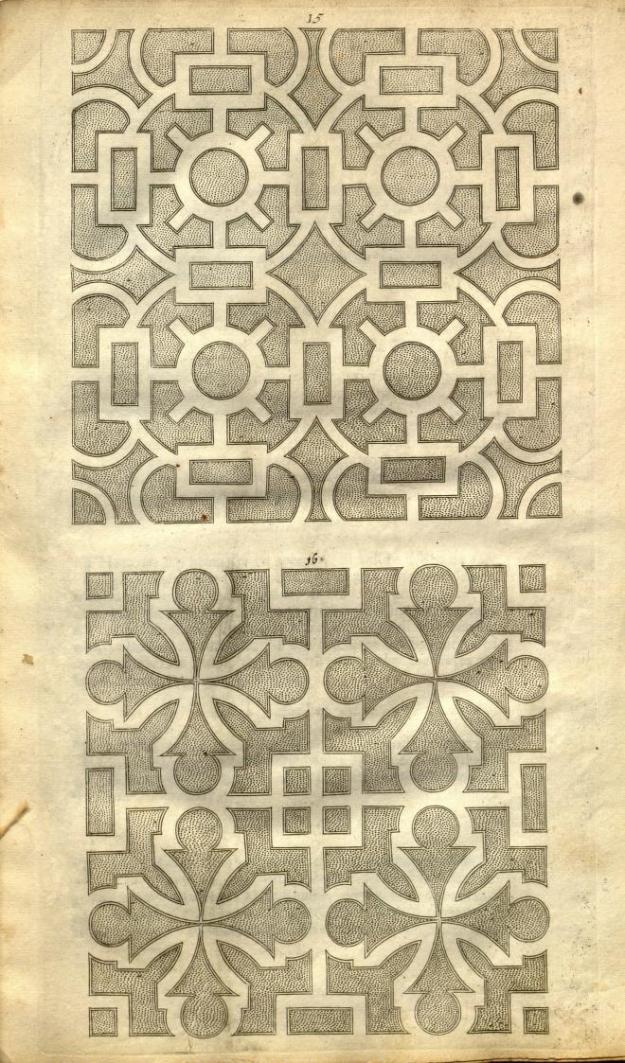

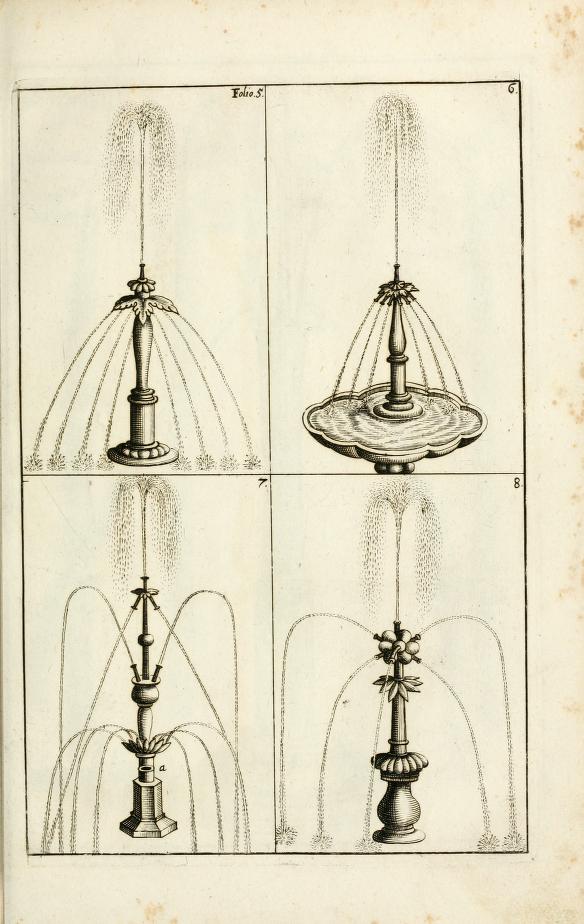

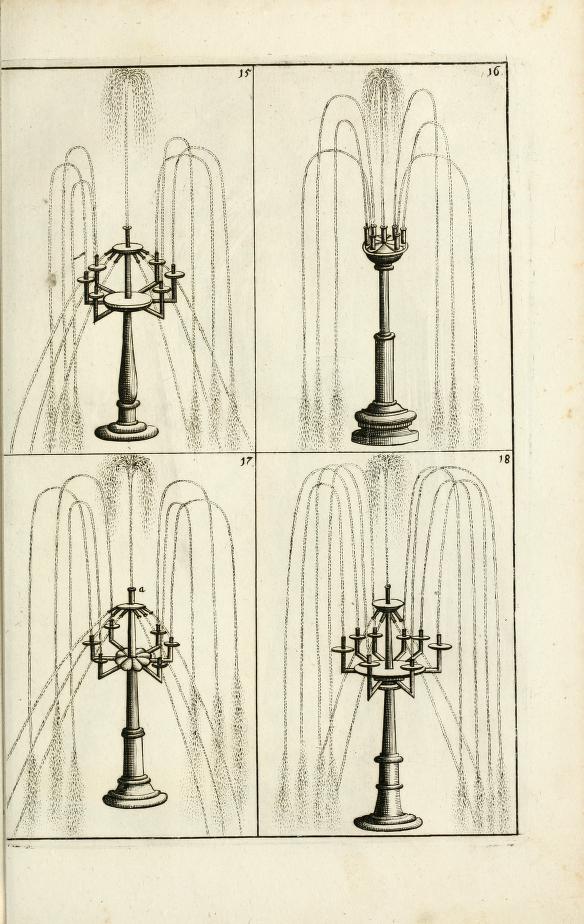

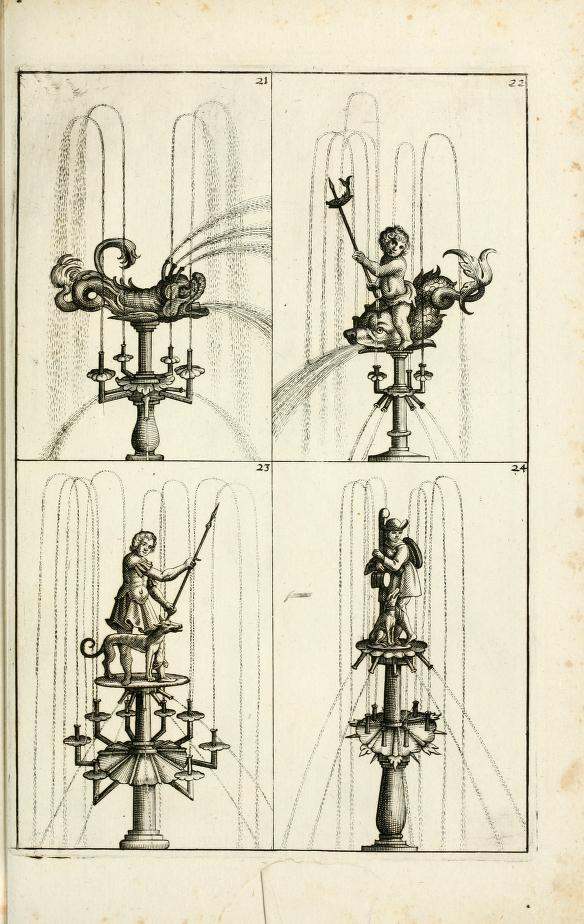

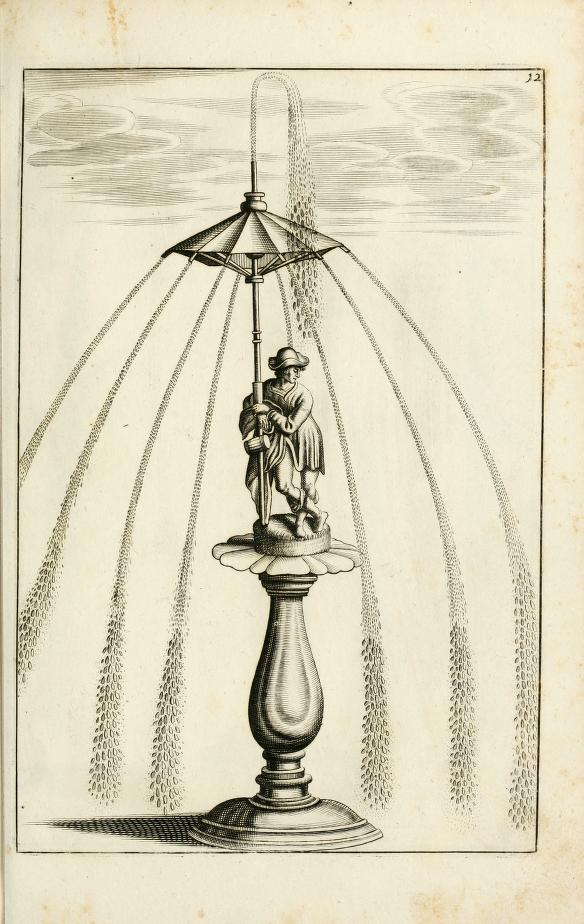

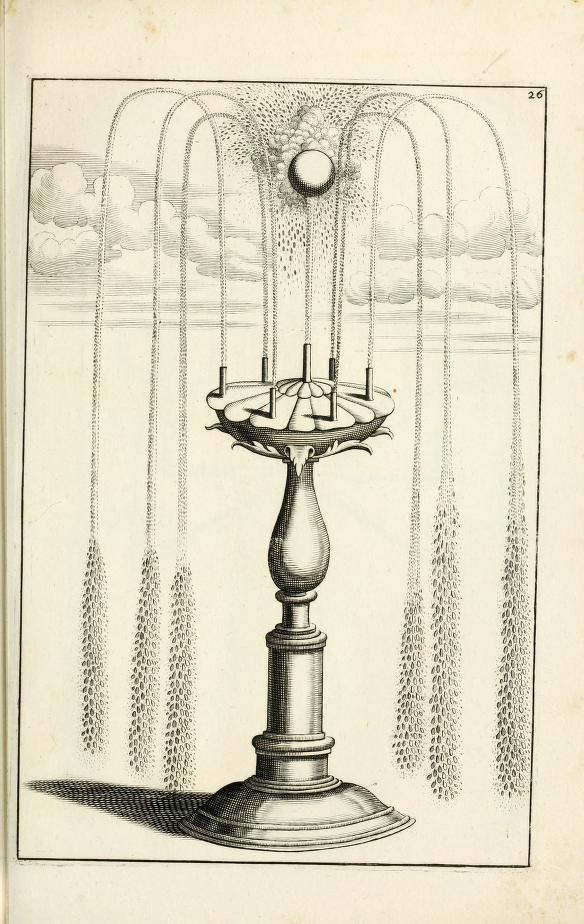

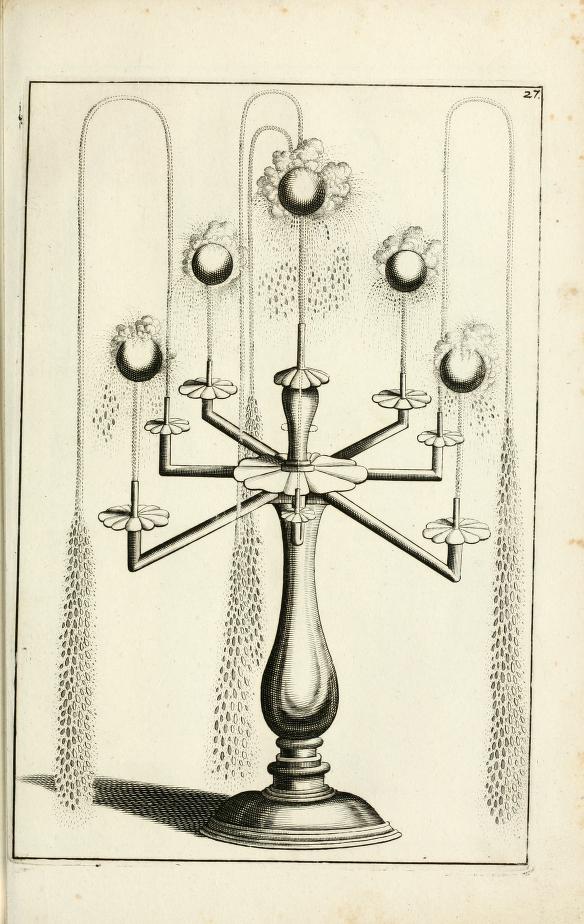

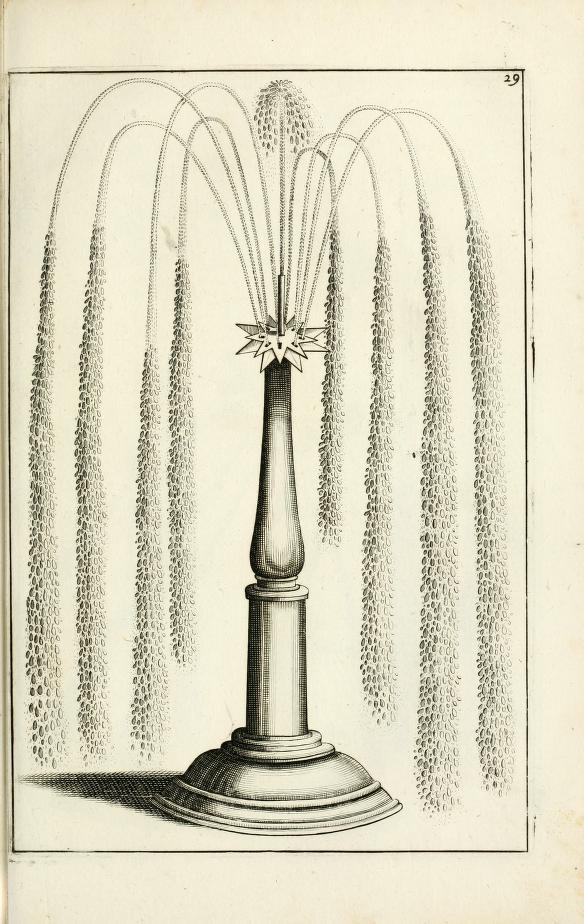

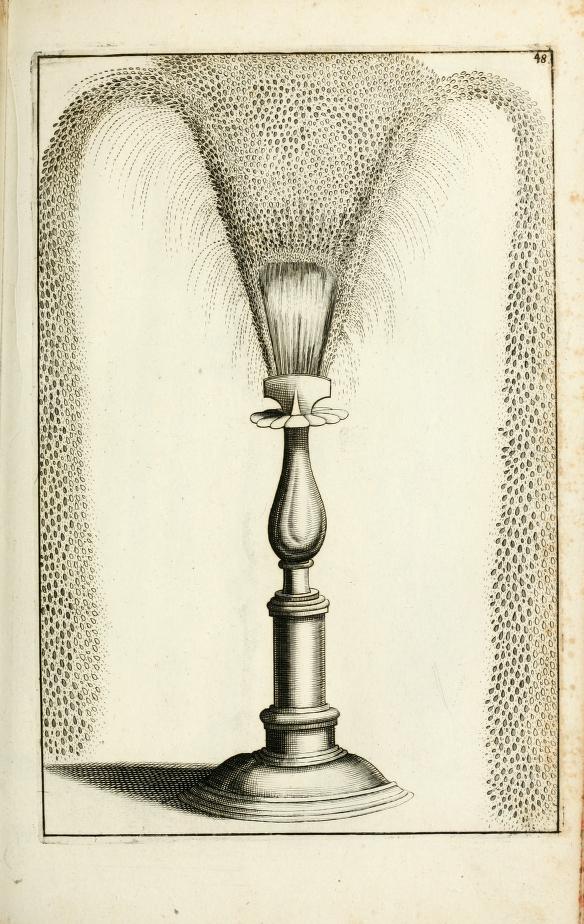

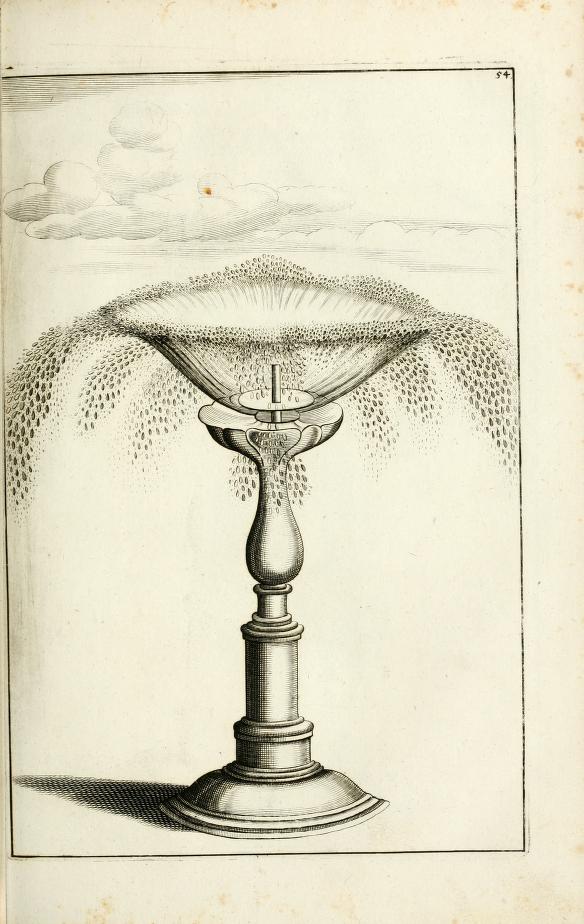

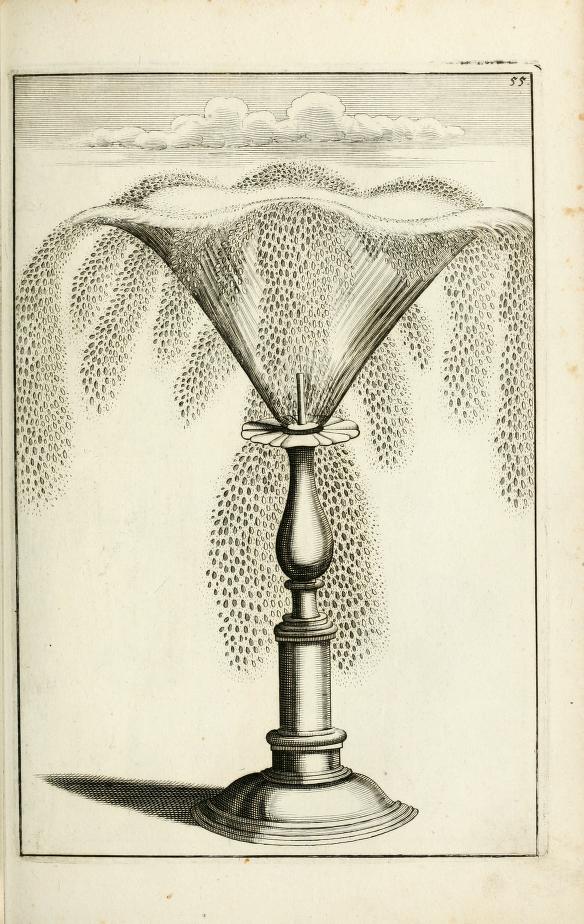

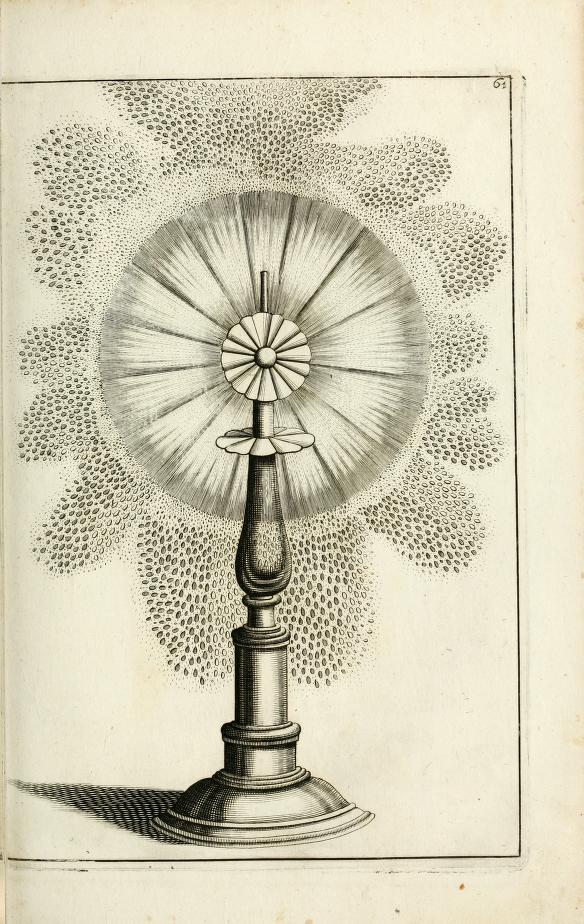

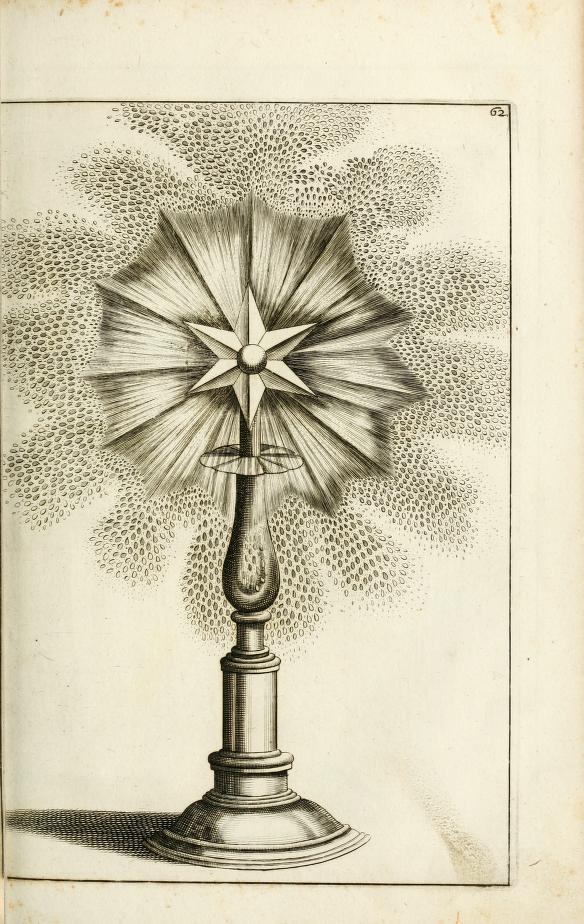

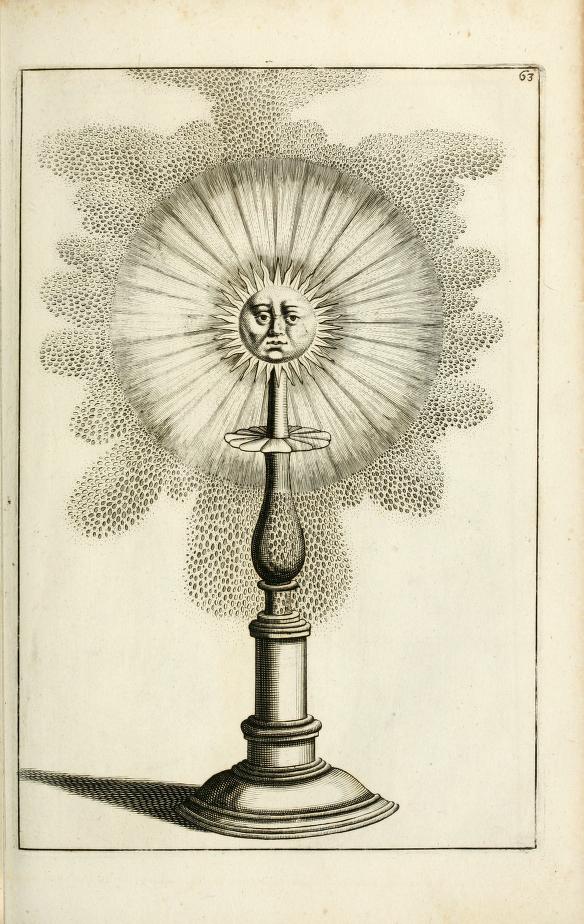

Livre de differants desseings de parterres by Daniel Rabel was published in Paris, in 1630 and these plates show a series of designs for his elaborate parterres.

Daniel Rabel (1578 – 1637) was an artist whose work included portraiture, botanical illustration and set designs and costumes for ballet. He also published several books and established a botanical garden in Blois in the Loire valley.

Rabel’s sophisticated designs are representations of intricate embroidery with plants used as coloured threads to create the overall appearance of a piece of richly decorated fabric.

The scrolling design of these parterres could be made out of low growing herbs; Rabel suggests rosemary, lavender, camomile and thyme. Sand would have been used for the compartimens or spaces in between the planting. Planning and constructing one of these parterres would have been a major task, making them an option for the wealthy. The embroidery effect could best be appreciated from an elevated position, from the windows of the house (or palace).

The French broderie parterres were developed at the beginning of the 17th century by Claude Mollet. The style was brought to England by Henrietta Maria after her marriage to Charles 1 in 1625, when she employed Mollet to modernise the royal gardens.

Could Rabel’s designs be used as inspiration for a garden today? Certainly they would be invaluable if you were recreating a parterre in a historic garden specific to 17th century France. But the formality and artificiality of the embroidery concept together with tight control of plants necessary to create such intricate patterns seems out of step with current taste which favours a naturalistic look and lower maintenance planting.

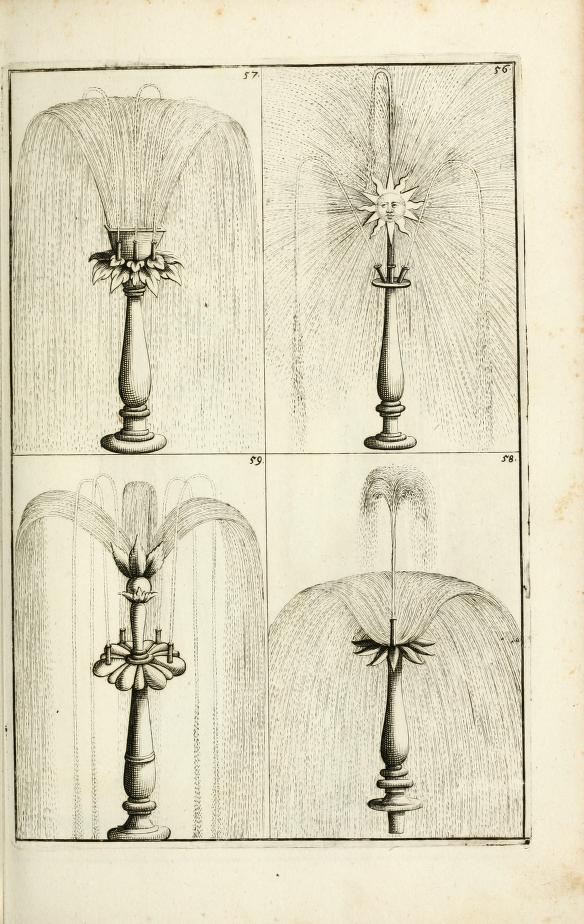

The charming, if romanticised, gardeners pictured at the front of the book have secured a good view of the parterre garden. She seems to have been gathering fruit while he poses with a spade and other gardening equipment including a large scissors, small sickle, watering can, rake and a line. He seems to be wearing loose cut culottes, a bit like plus fours.

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/33324#/summary