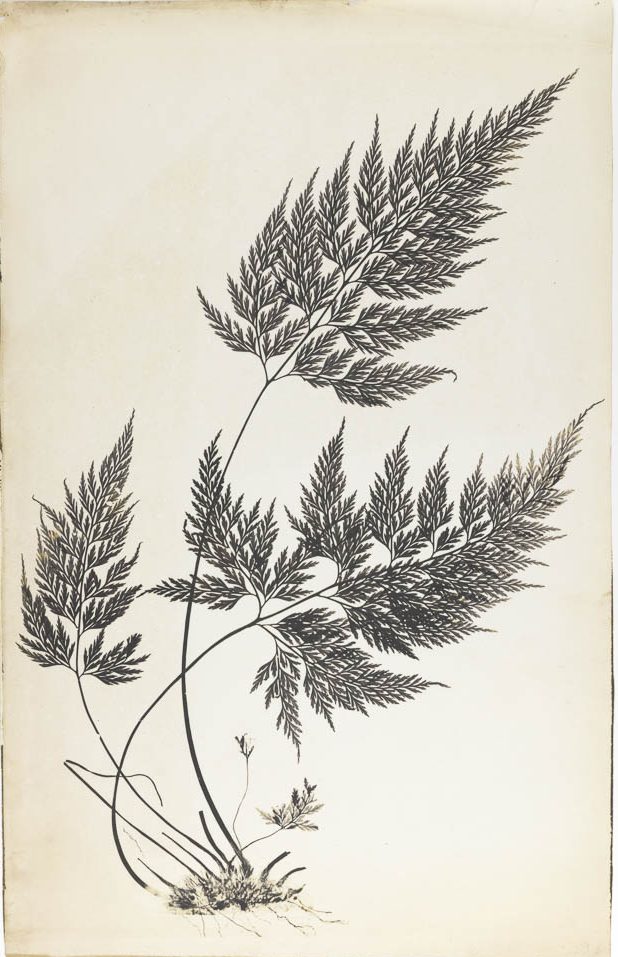

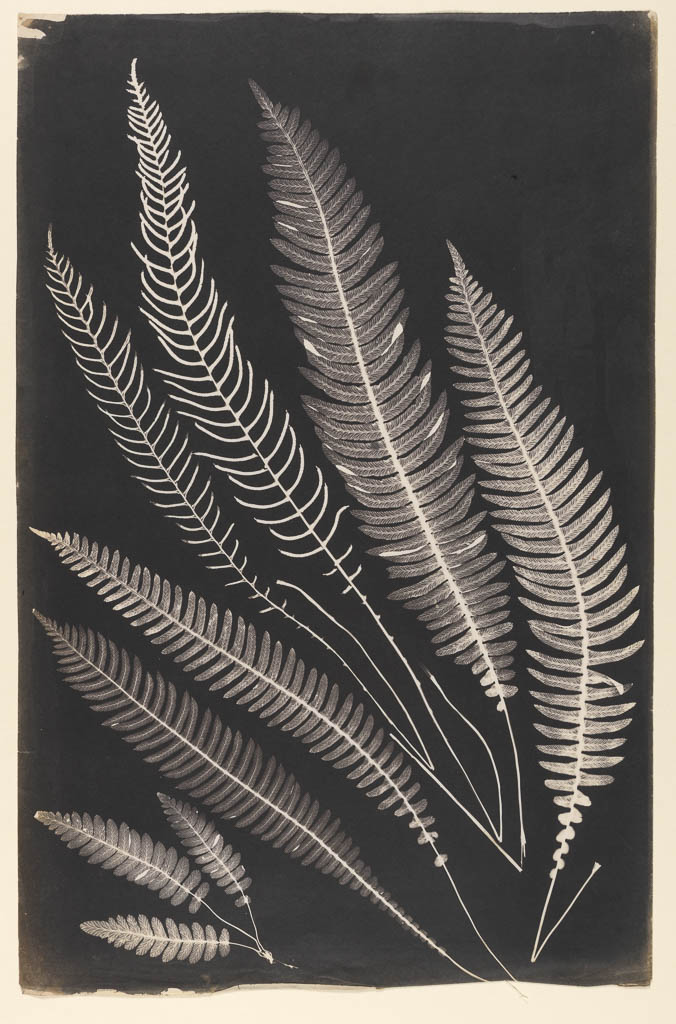

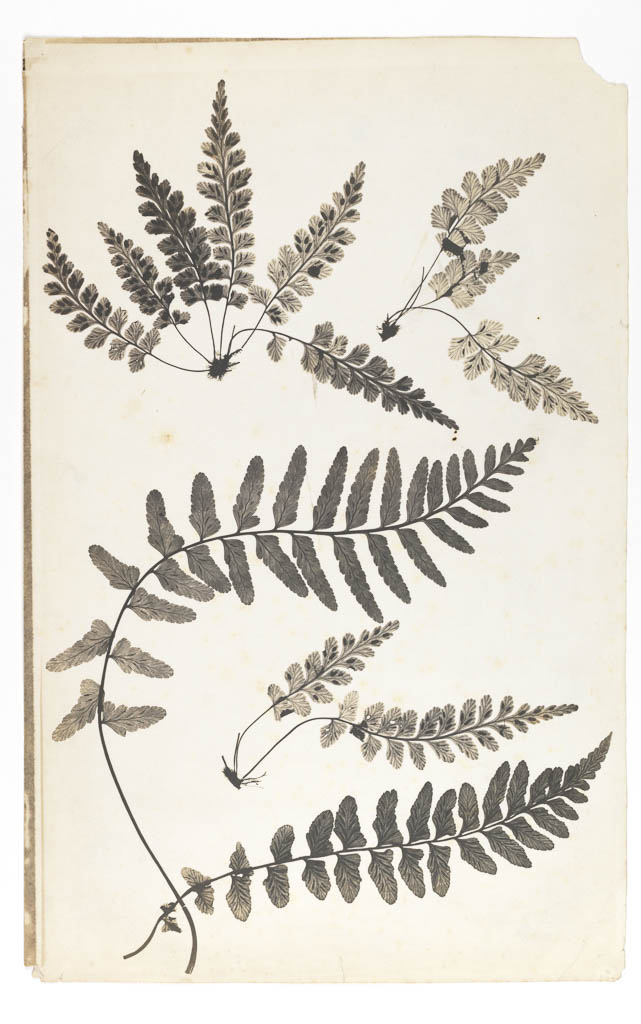

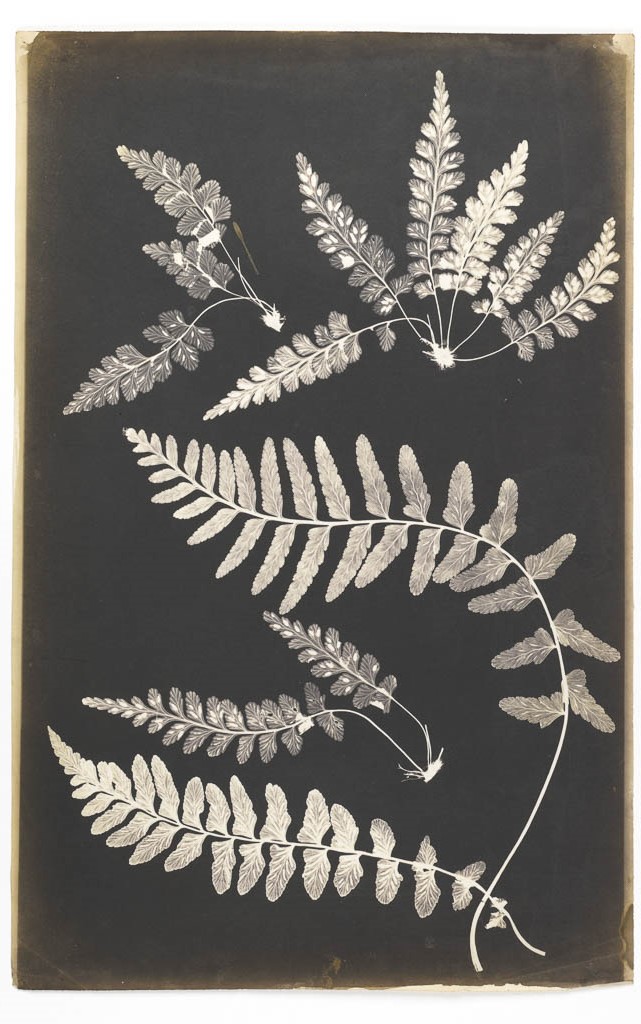

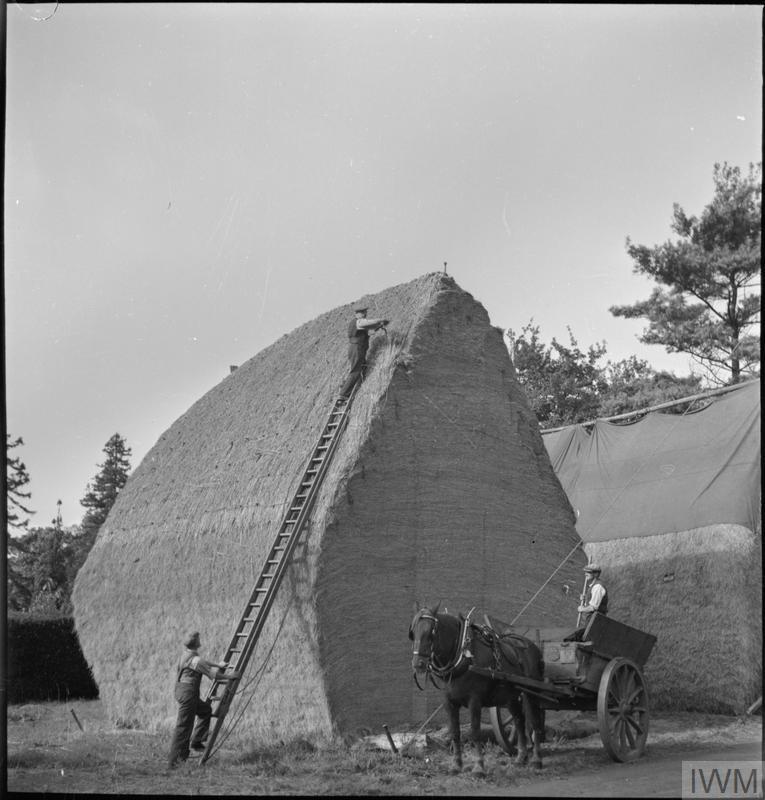

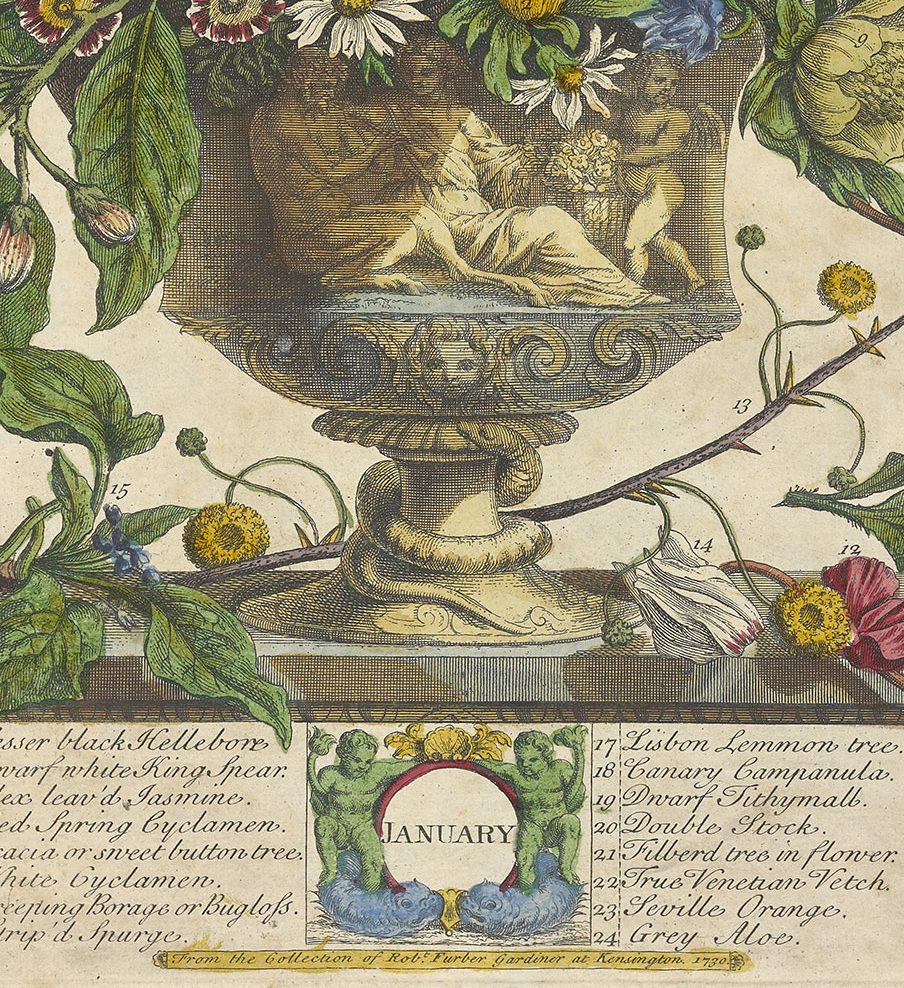

January from Twelve Months of Flowers produced by Robert Furber 1730. The Morgan Library & Museum

Perhaps it’s during the short days and dark nights of January that we experience most a longing for fresh flowers. Especially welcome are the first of the snowdrops and winter aconites; flowers so small they might be lost in the profusion of summer. But now, emerging from the cold soil in this dormant season, they bring delight as they anticipate the coming of spring.

In a month where flowers are generally scarce, gardener Robert Furber’s astonishing bouquet representing January has apparently conquered the seasons with a super-abundance of blooms. Alongside snowdrops and winter aconites, long sprays of fragrant citrus blossom are accompanied by stems of hyacinth, cyclamen, and anemone, the arrangement centered by two spectacular aloe flowers in red and gold.

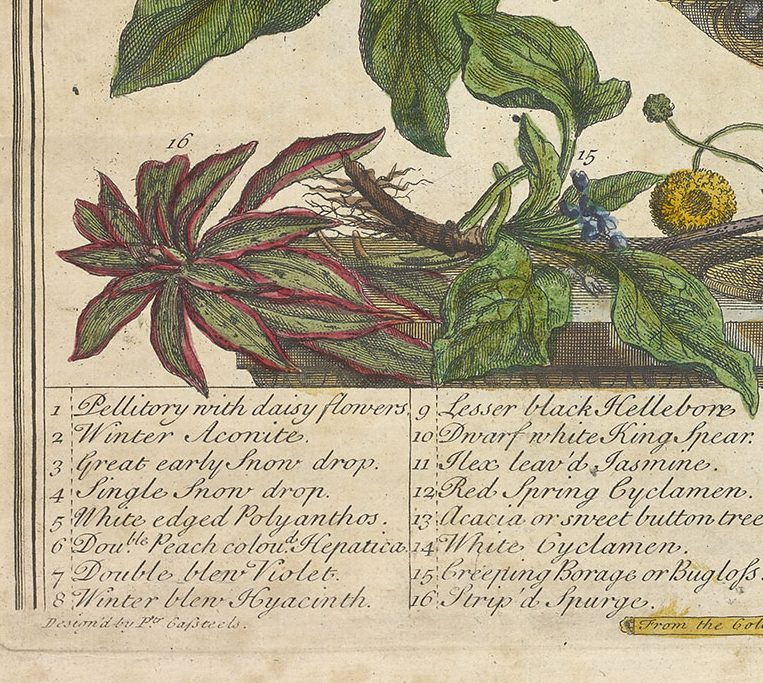

Twelve Months of the Flowers published in 1730 by Robert Furber (1674 – 1756) is a series of engravings for every month of the year, designed in the style of Dutch flower paintings and featuring upwards of thirty blooms in each arrangement. To produce the series, Furber’s collaboration with artist Pieter Casteels (1684 – 1749) and engraver Henry Fletcher (active between 1710 – 1750) involved each party investing £500 into the venture. Public subscriptions and further sales after publication soon pushed them into profit. The plates were originally sold for £1 5s in uncoloured form, or £2 12s 6d for a coloured version.

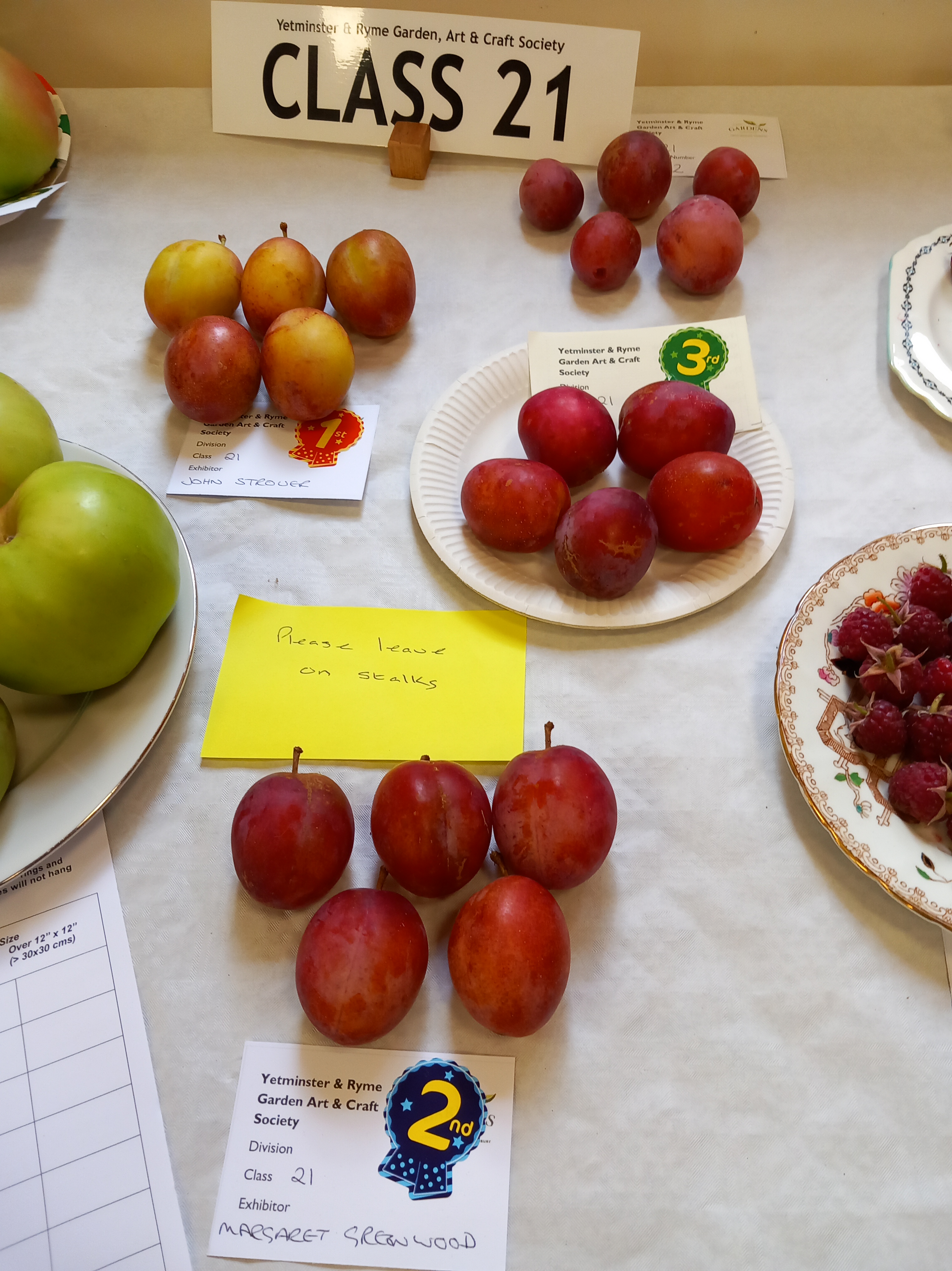

All the plants featured in the engravings were sourced from Furber’s nursery in Kensington from which he and his colleague John Williamson supplied clients with an extensive stock of tender plants raised in greenhouses, sought after bulbs and a comprehensive range of fruit trees.

Furber was a master of marketing and understood the power of the image to drive sales. By producing this set of twelve high quality engravings, desirable objects in themselves, he positioned himself both as an expert horticulturalist, and as a person of taste, from whom similarly discerning customers could buy the choicest blooms for their houses and gardens with the greatest confidence. If Furber was around today, he would doubtless be across all the social media channels with thousands of followers on Instagram.

Furber’s Twelve Months of the Flowers also speaks of a desire to regulate nature to a human timetable, especially by use of the heated greenhouse to force plants and to extend the seasons. This approach has become a way of life for us now, with so many of our flowers, soft fruit and salad crops produced in this way.

Helpfully, each flower in Furber’s engravings has been given a number corresponding to a list at the base of each engraving, identifying individual plants and providing an important visual record of the range plants available in the UK in the early 18th century. Here follow some observations about the flowers that brightened January days in the 1730s. Links below:

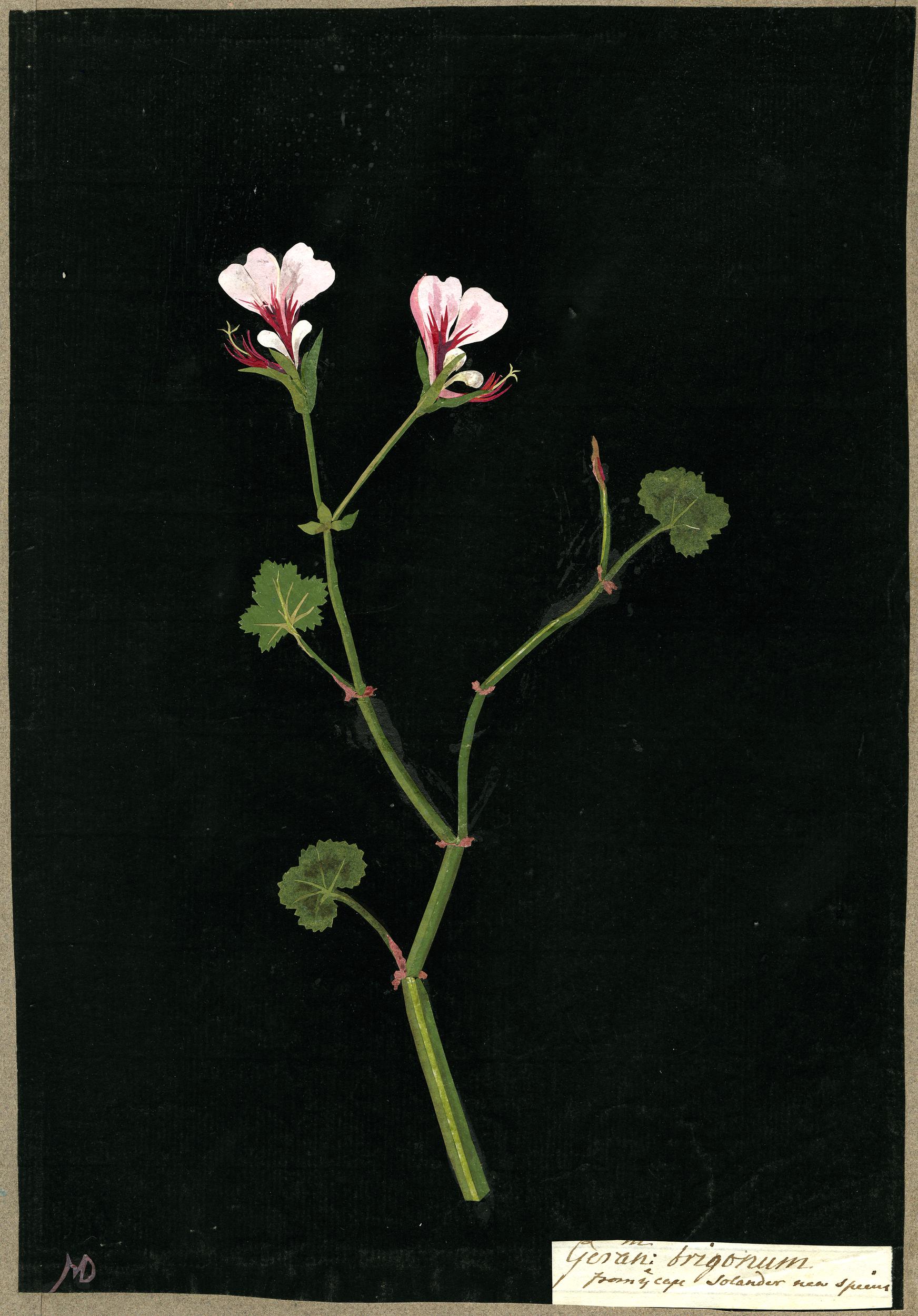

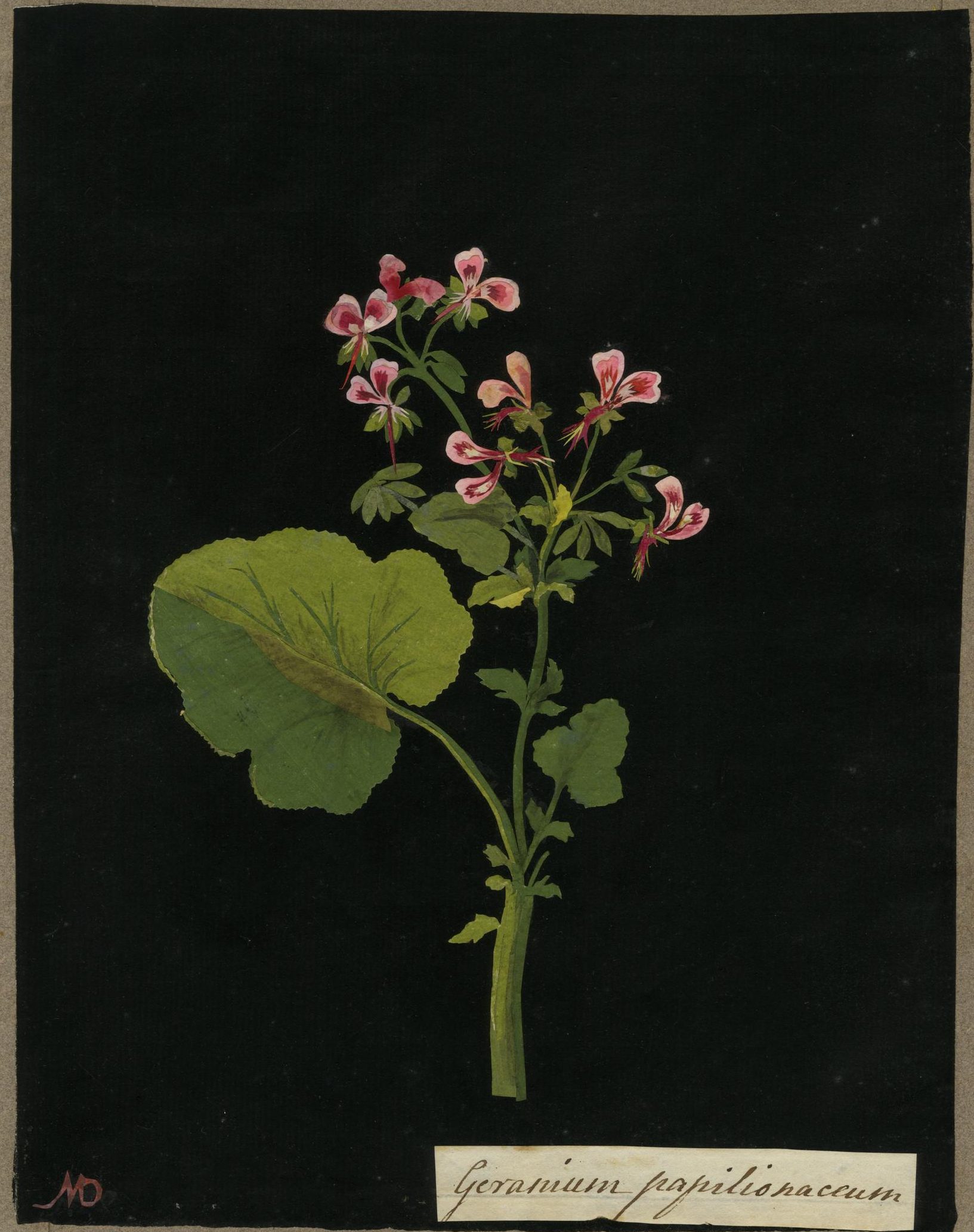

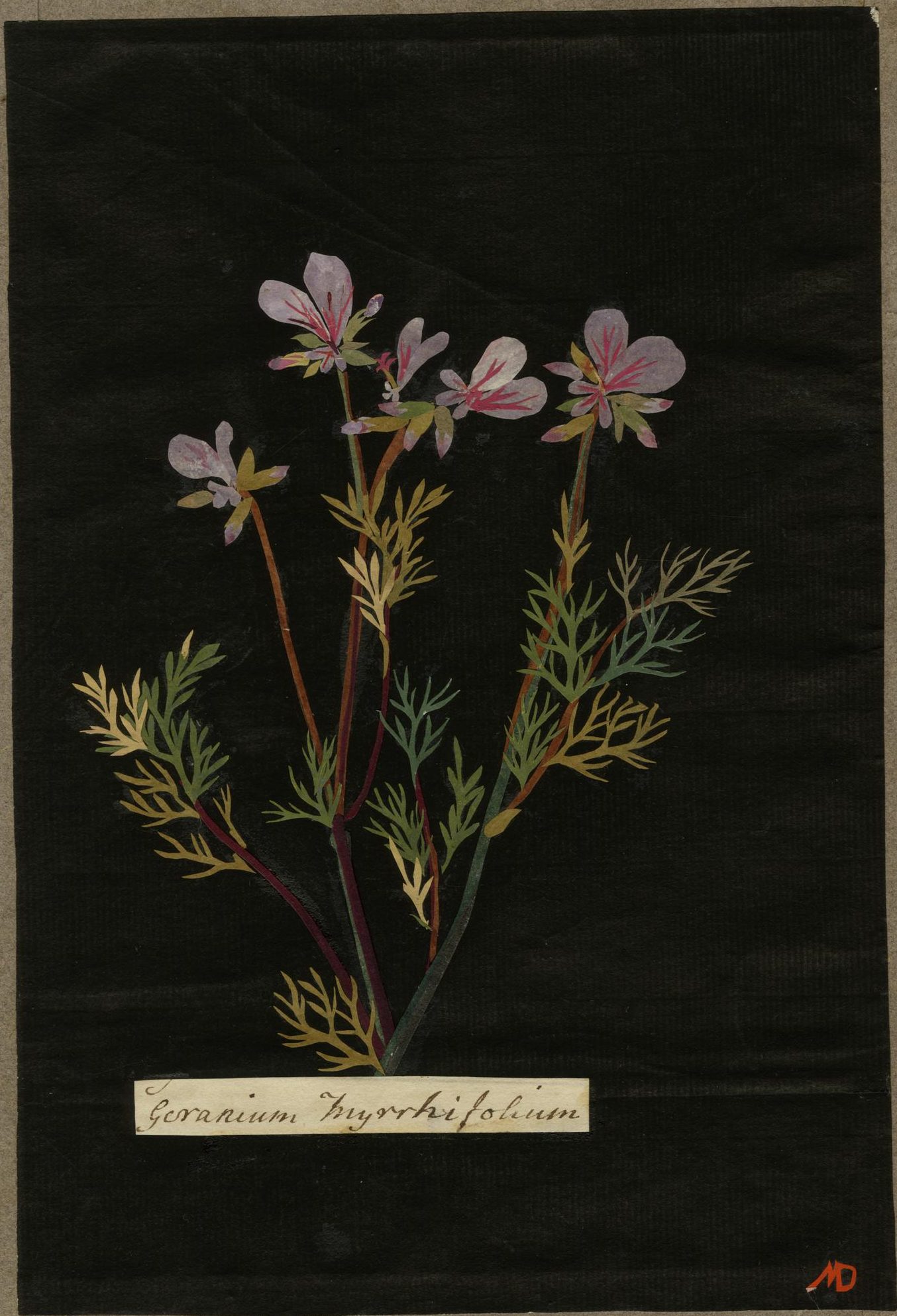

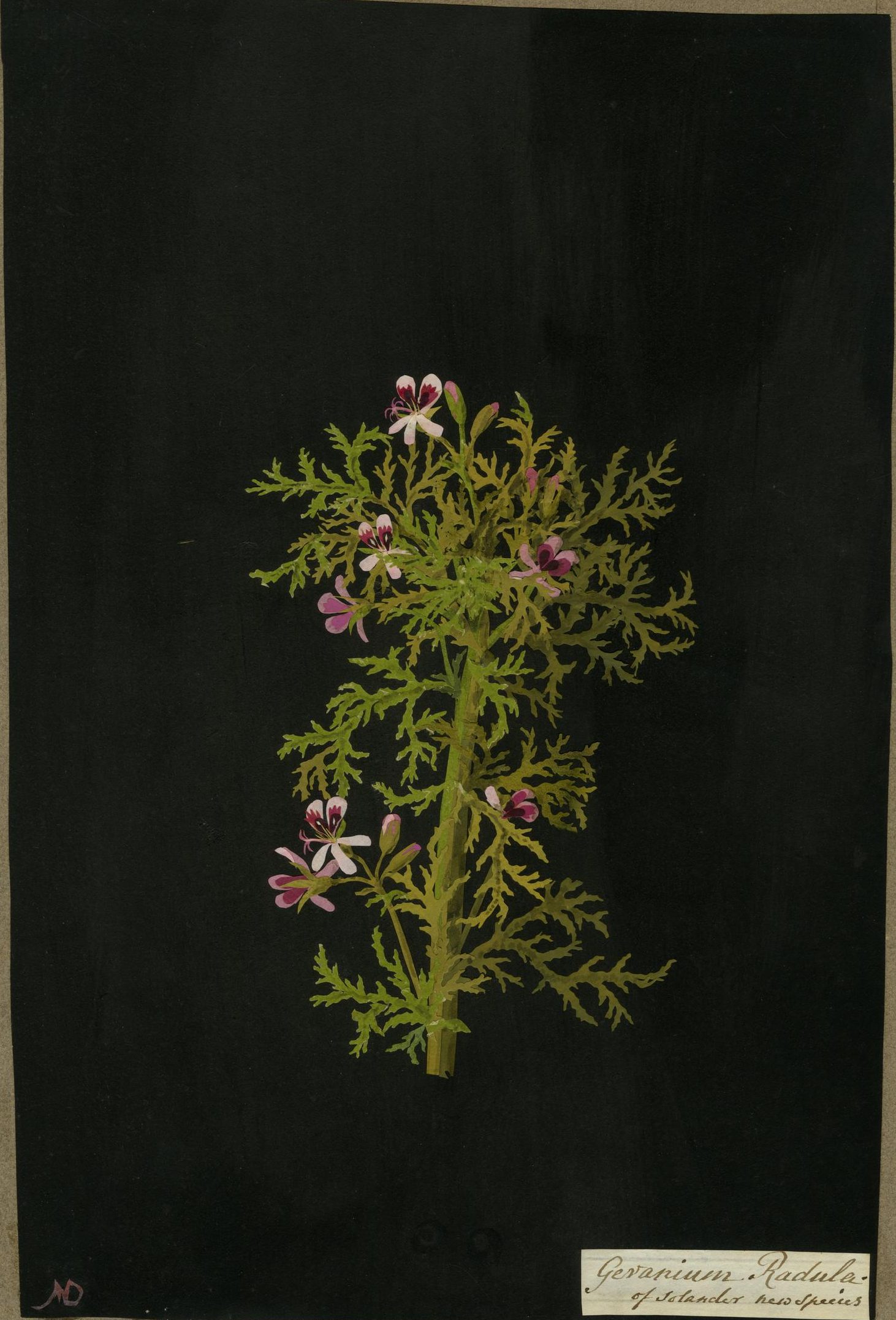

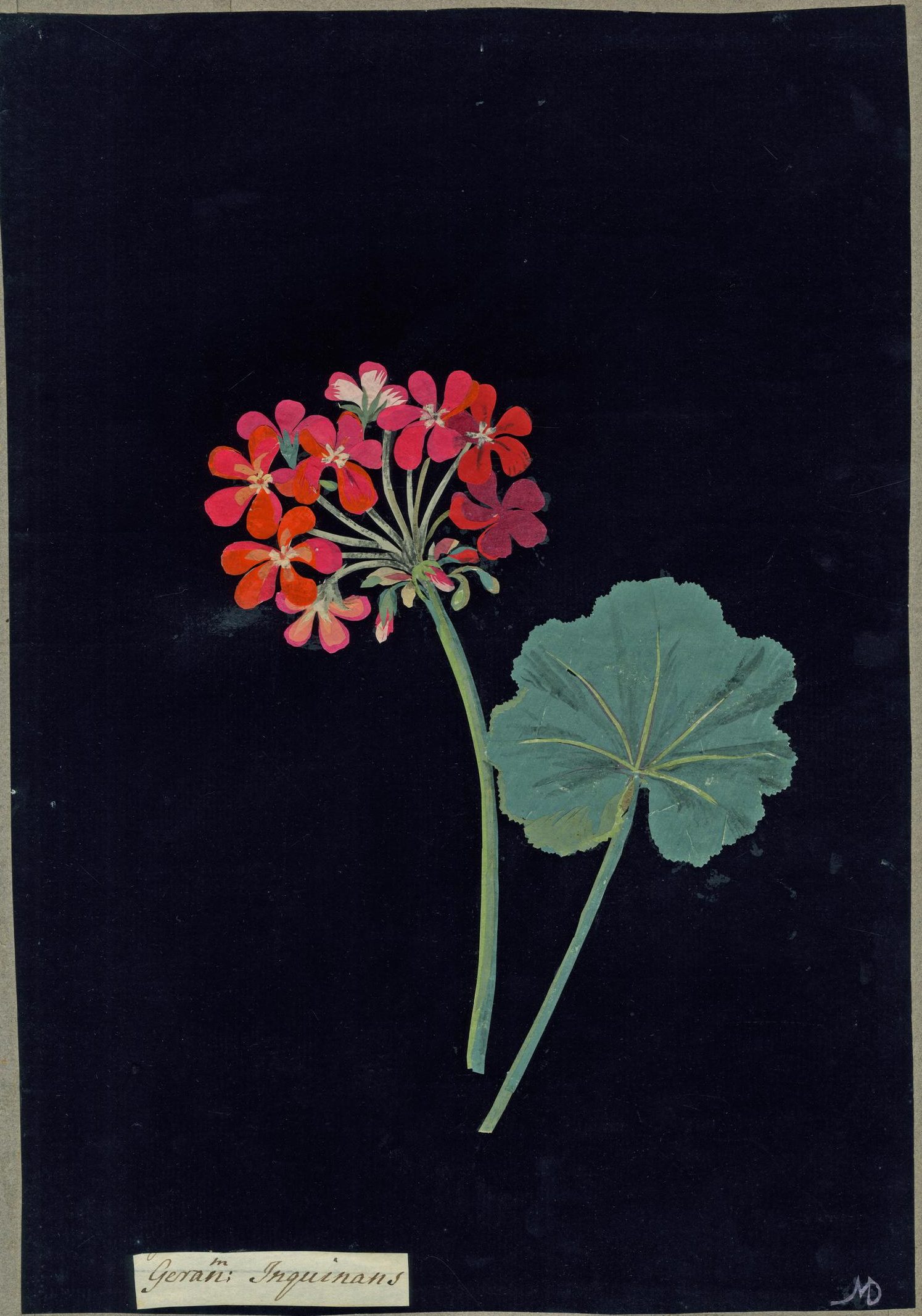

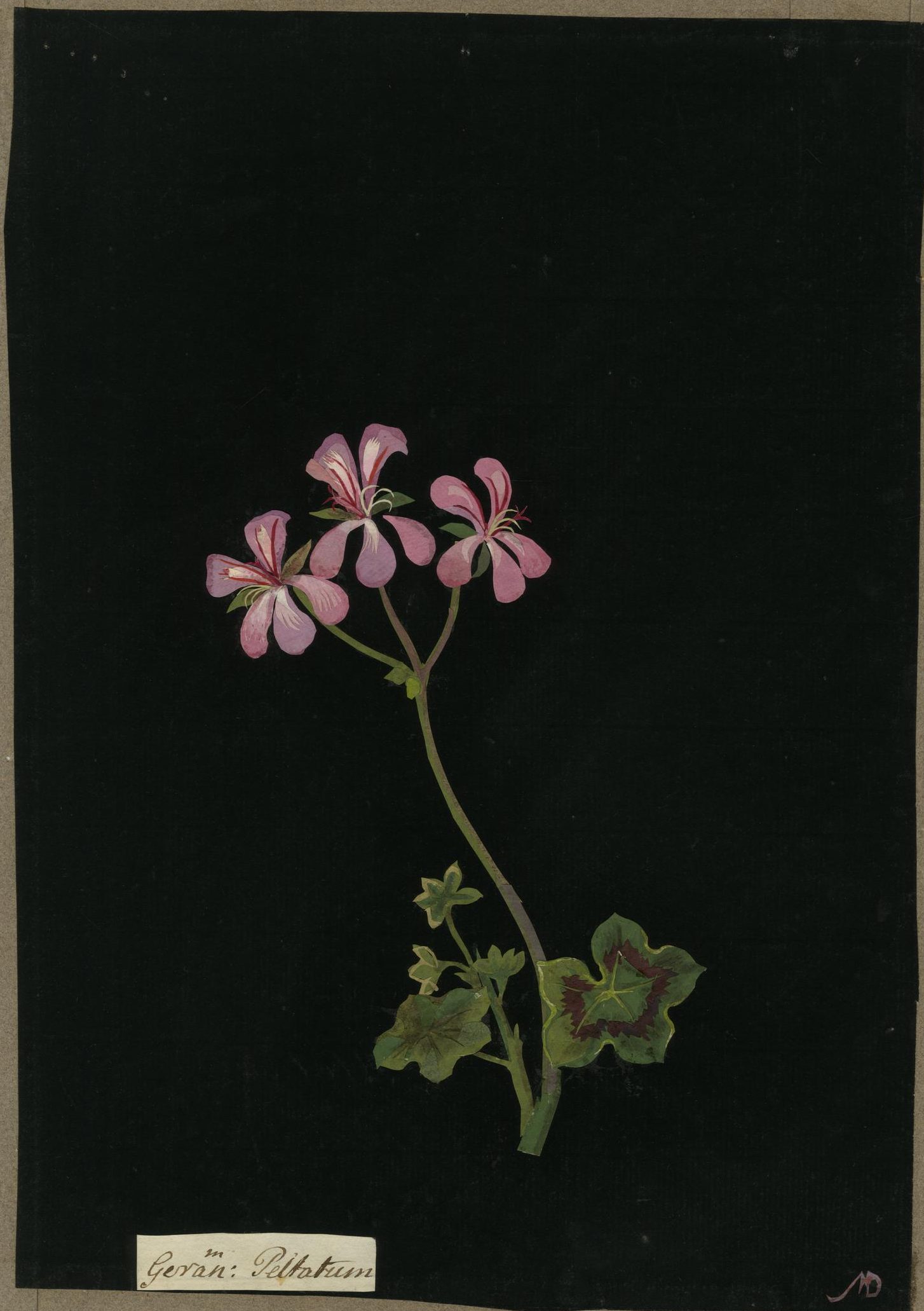

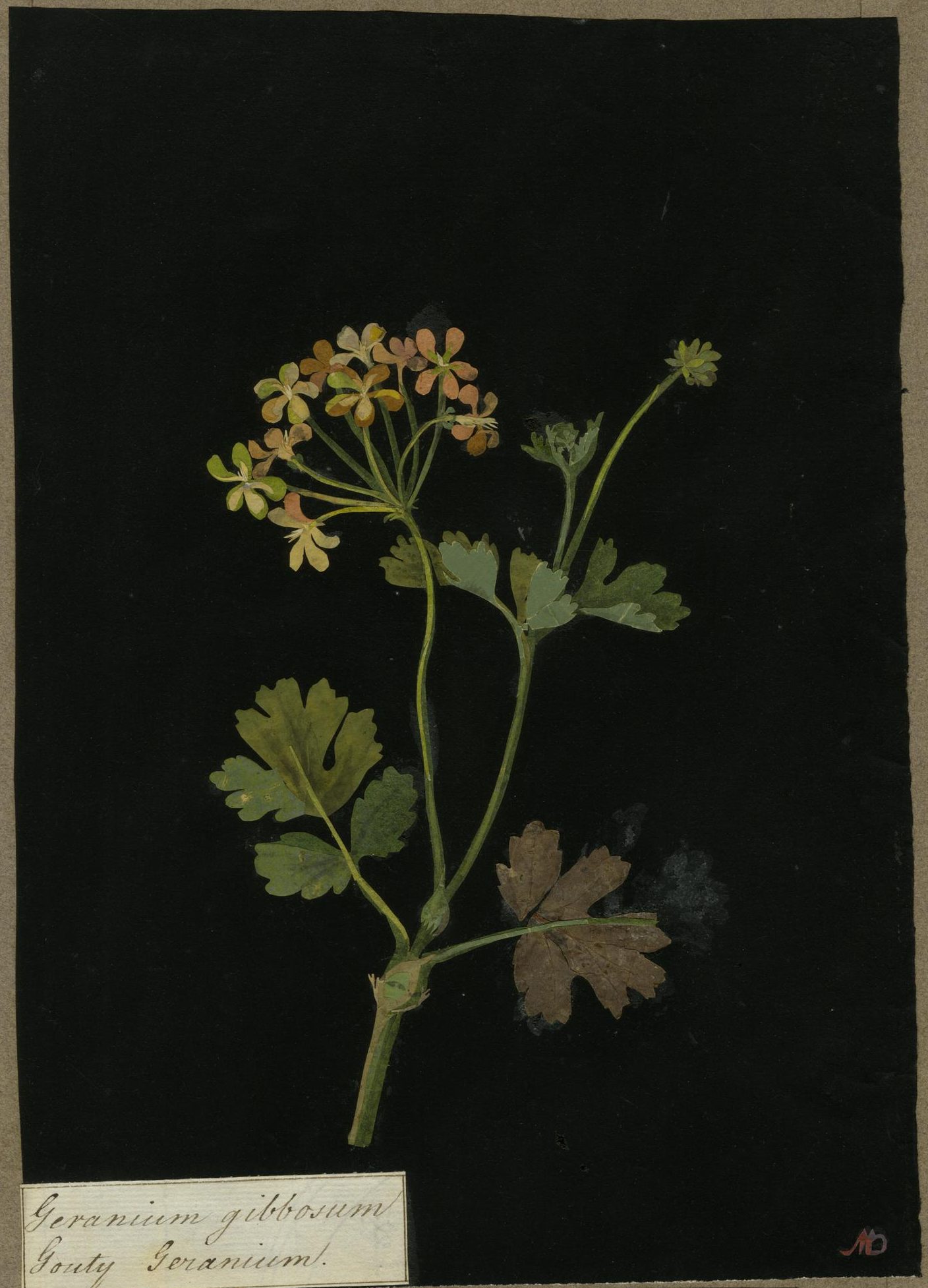

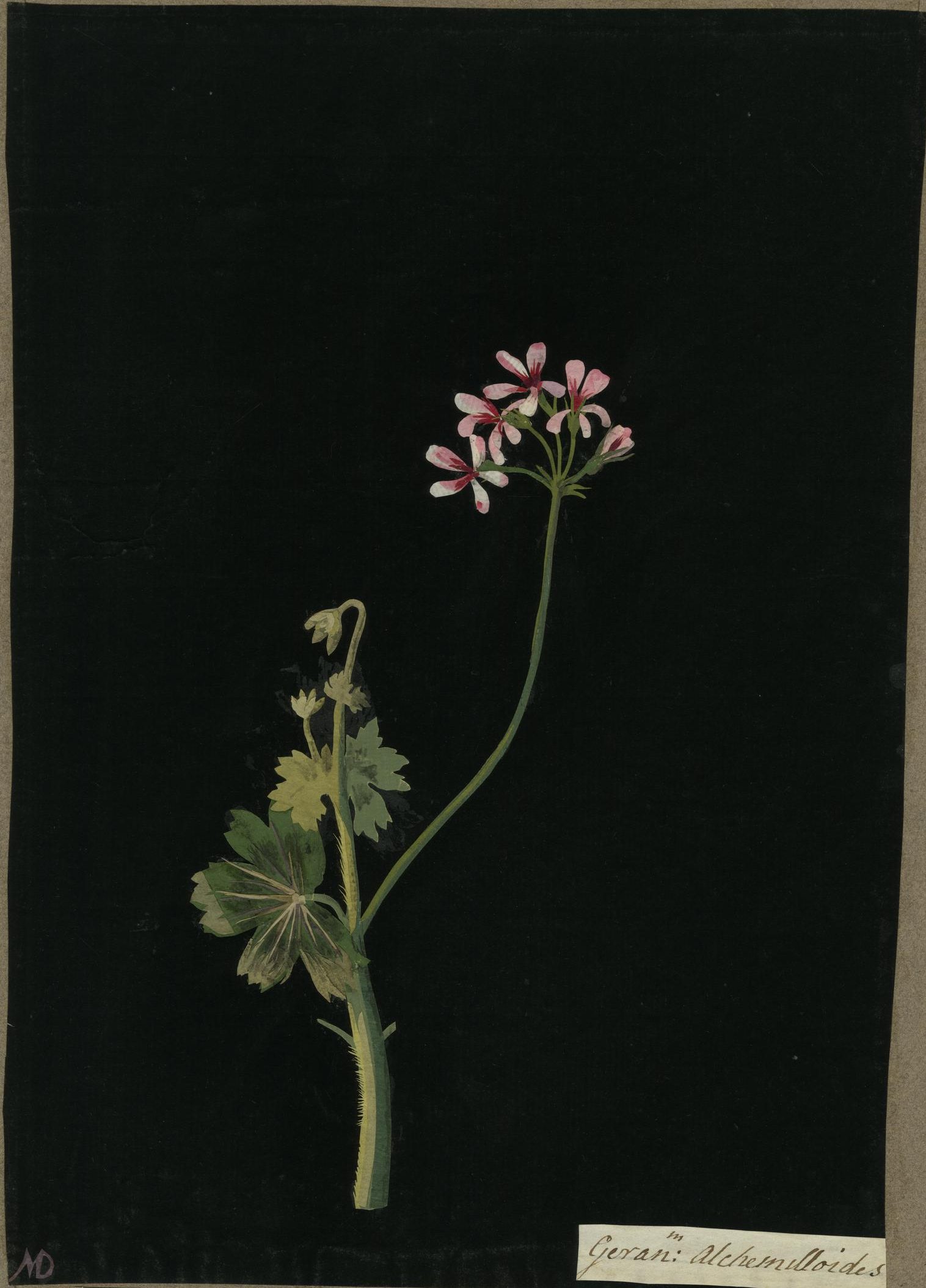

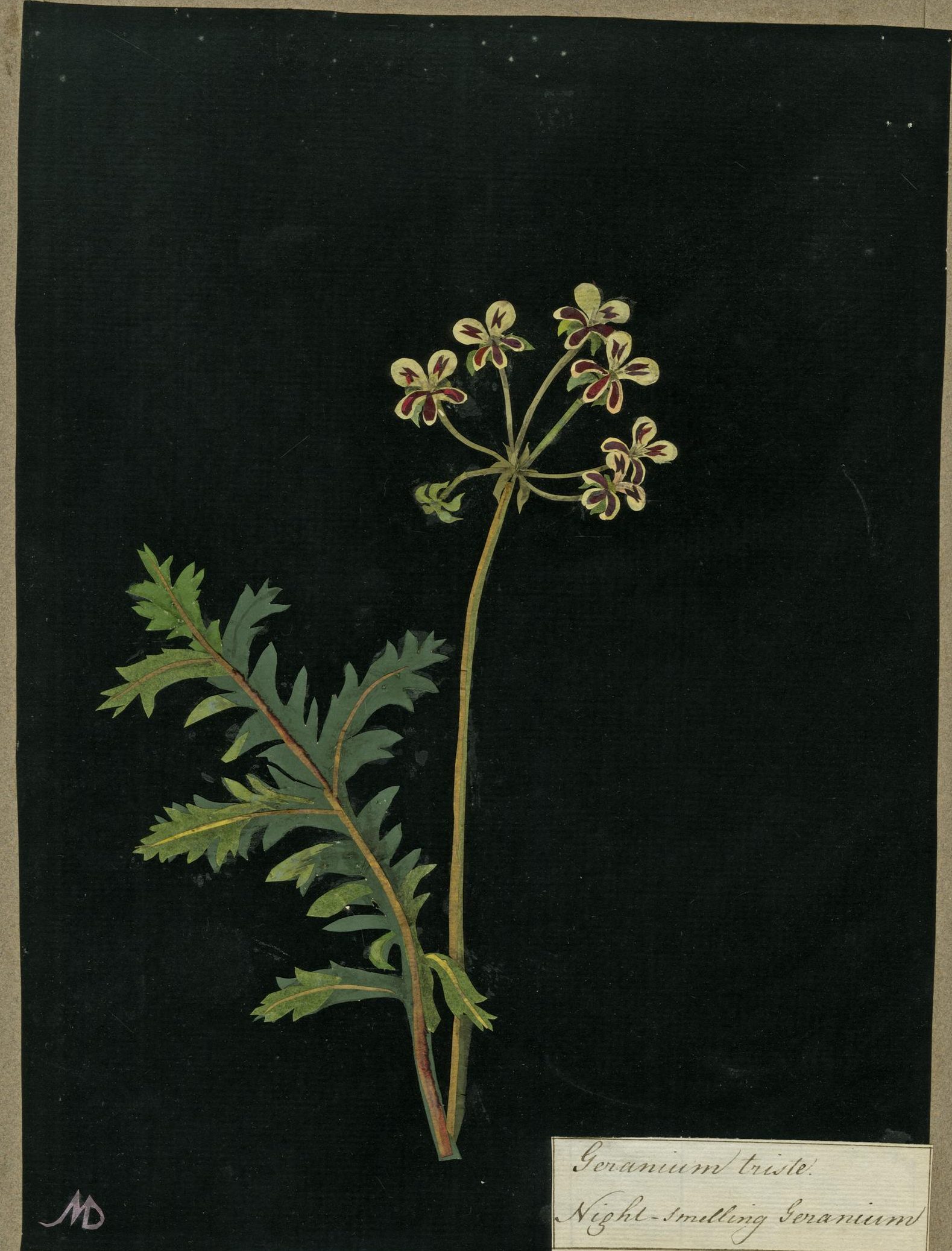

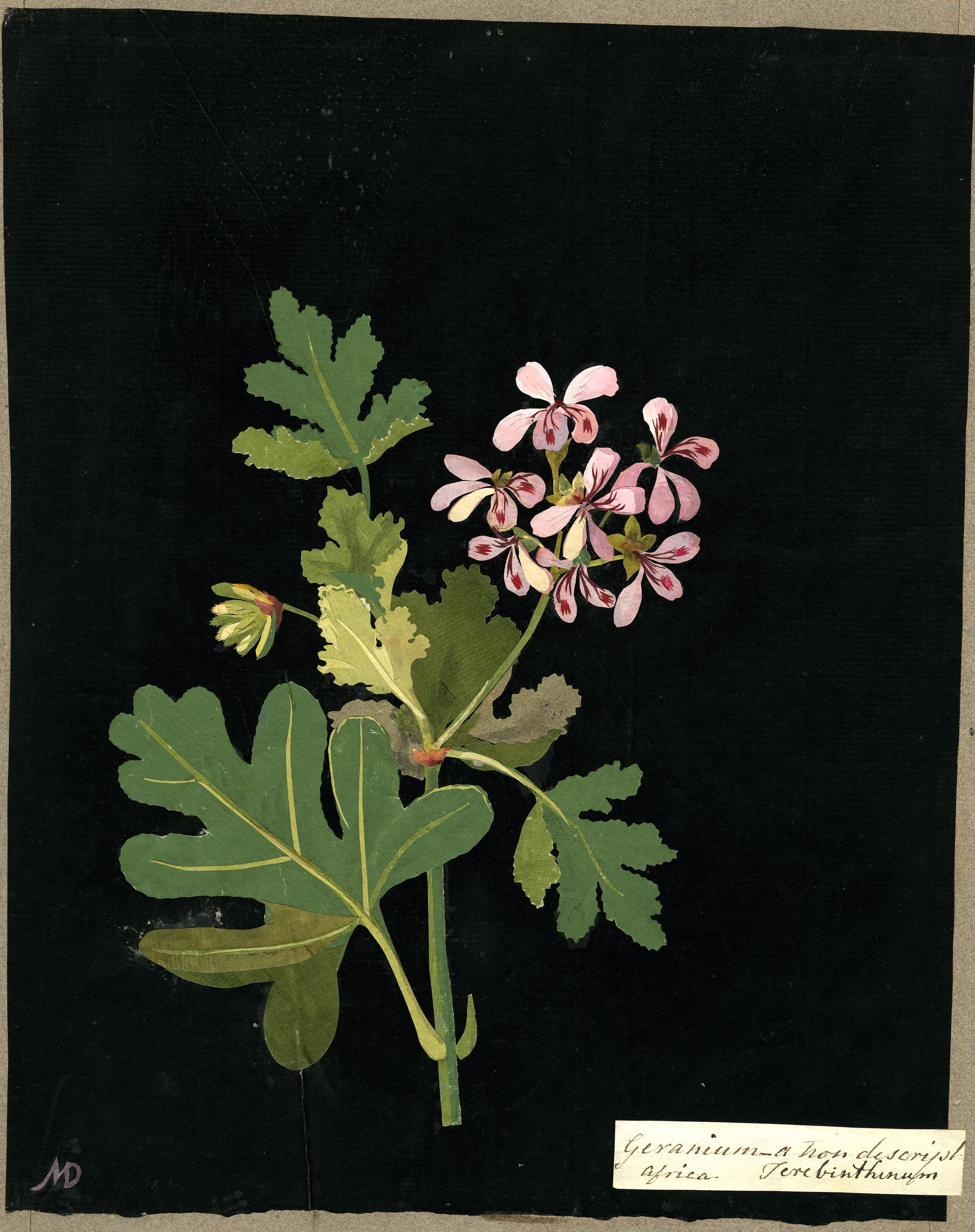

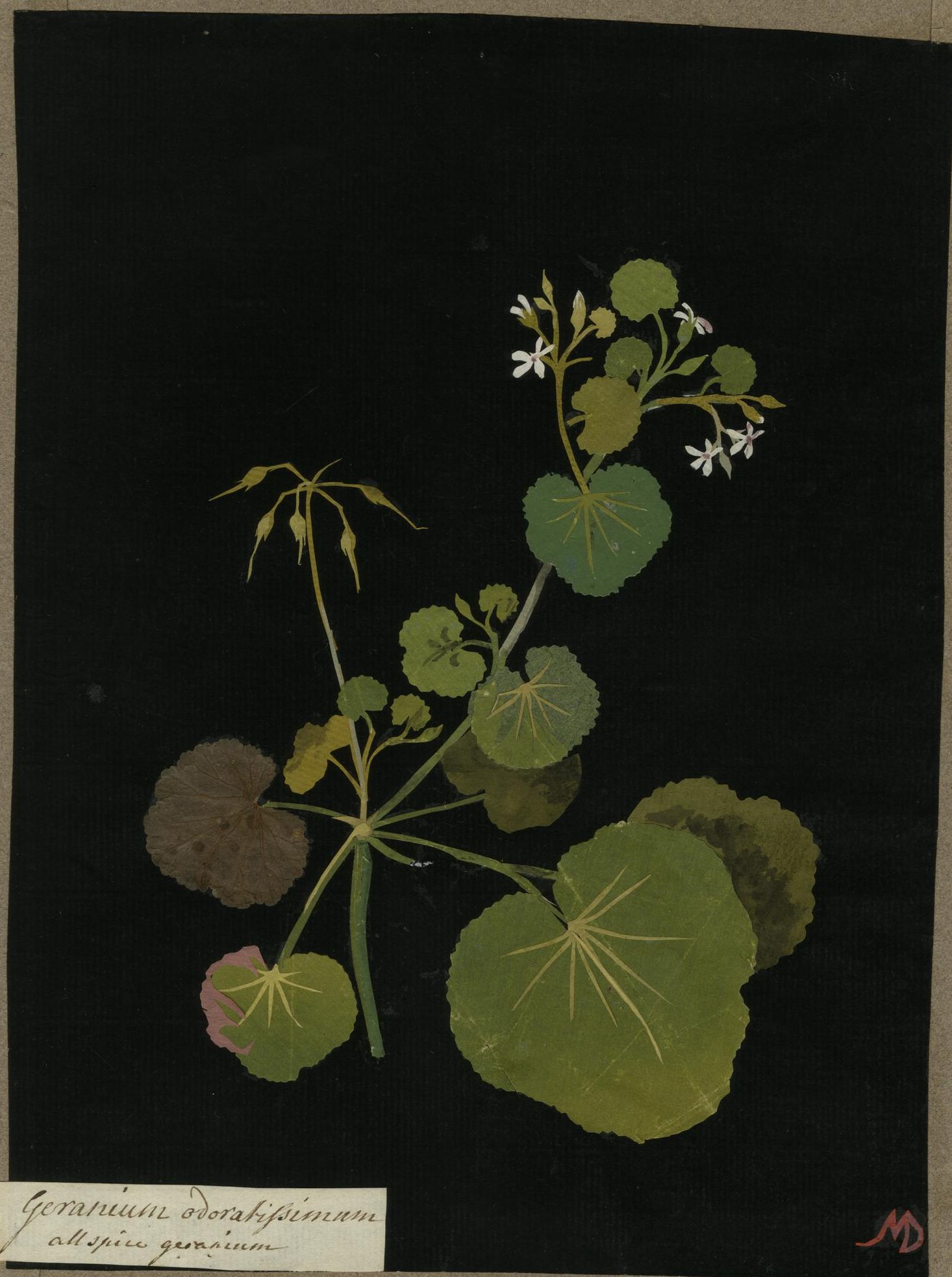

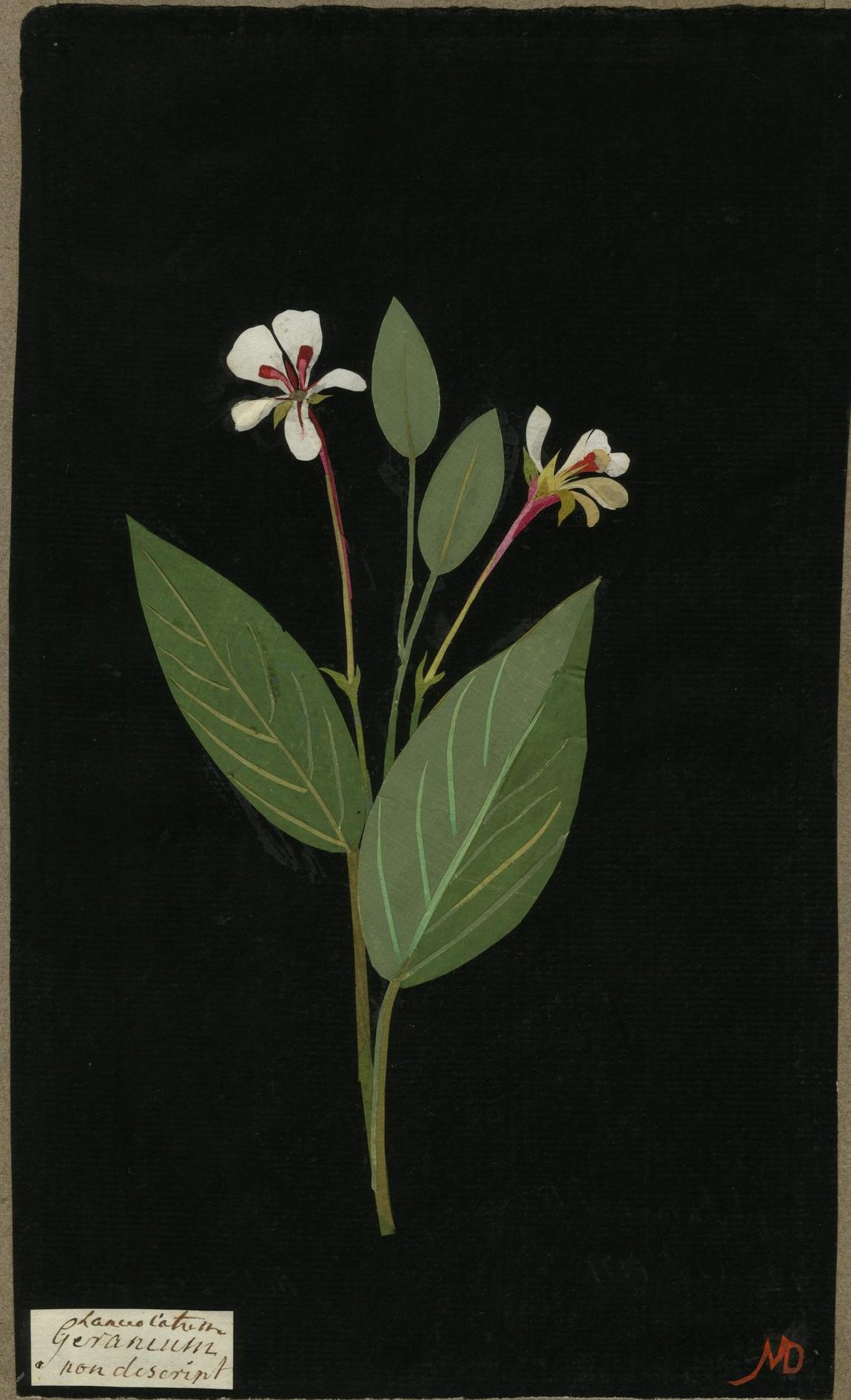

Grey Aloe (24) and Spotted Aloe (26) Aloes from South Africa and the Canary Islands were popular greenhouse plants in the 18th century, recorded by artist Mary Delany and recommended by author and East London nursery owner Thomas Fairchild.

(23) Blossom of the Seville orange, whose fruits are used to make marmalade and (21) Filberd tree in flower. Amongst the exotic blooms, this branch of common hazel shows the beauty of both the catkins and bright red female flowers.

(30) The Strip’d Orange just coming into flower has green leaves bordered with yellow. (3) Great early Snow drop (4) Single Snow drop, (28) Tree Savory.

(25) Winter white Hyacinth. This long, elegant stem with widely spaced flowers looks quite different to modern hyacinths where the flowers are bunched much closer together in the familiar cylindrical shape. (20) Double stock, (32) Tree Sedum, (5) White edged Polyanthus, (2) Winter Aconite, (1) Pellitory with daisy flowers, possibly Anacyclus pyrethrum or Spanish chamomile.

(18) Canary Campanula, most likely Canarina Canariensis the Canary Island Bellflower a fast growing climbing plant, grown from a tuber. (17) Lisbon Lemon Tree, (16) Strip’d Spurge. We know striped flowers like tulips and pinks were still immensely popular in this period and it would appear plants with multicoloured leaves were also valued as ornamentals in the garden. (15) Creeping Borage or Bugloss.

(31) Strip’d Candy tuft shown here with white flowers and variegated leaves, (6) Double Peach Coloured Hepatica, (7) Double blew Violet, (8) Winter blew Hyacinth, (9) Lesser black Hellebore, (10) Dwarf white King Spear, possibly a species of Asphodelus, common in the Mediterranean growing in stony ground. (13) Acacia, or sweet button tree, possibly Acacia farnesiana, a plant with a wide distribution in the Americas, (11) Ilex leav’d Jasmine, (12) Red Spring Cyclamen, (14) White Cyclamen.

Beneath the cartouche for the month of January the legend says, ‘from the Collection of Robt Furber Gardiner at Kensington. 1730

Design’d by Ptr Cassteels

Engrav’d by H Fletcher

Further reading:

Twelve Months of Flowers at The Morgan Library & Museum here

Robert Furber Wikipedia here

The Catalogues of Robert Furber, The Garden History Blog here

Pieter Casteels Wikipedia here

Henry Fletcher, Wikisource here