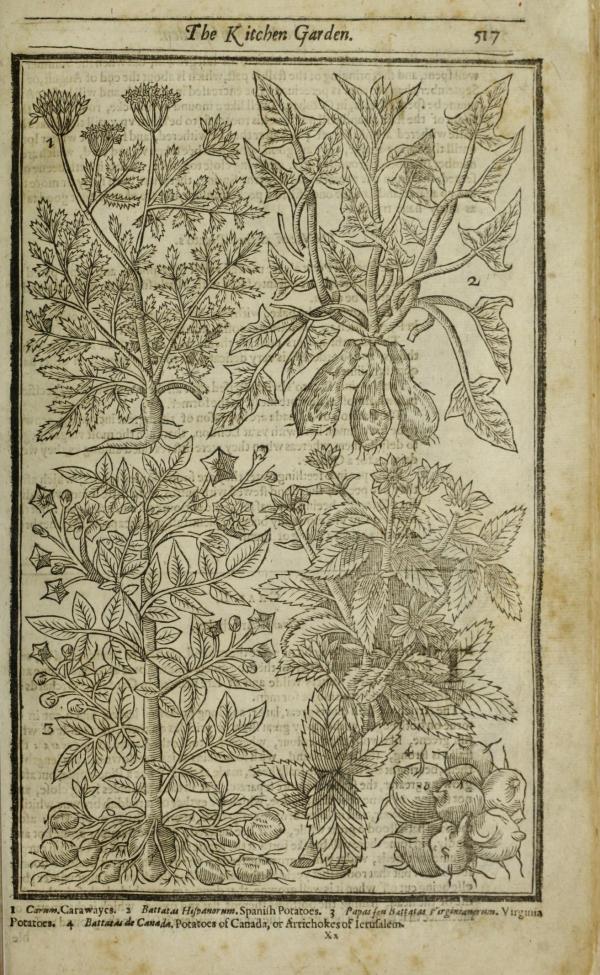

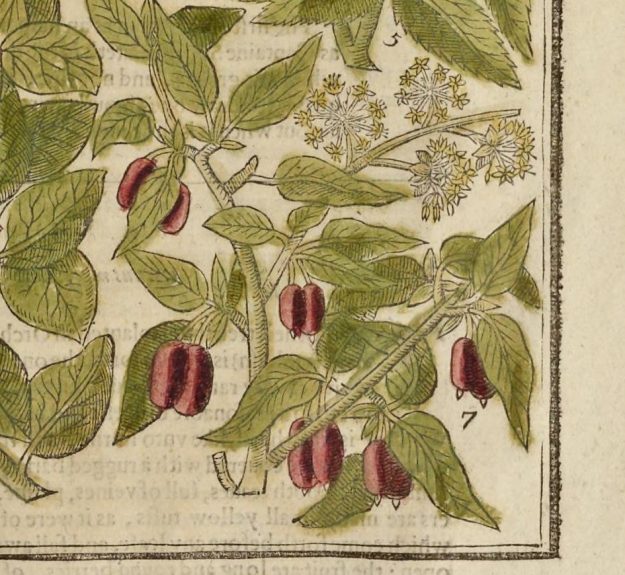

1. The true Service tree 2. The ordinary Service tree 3. The common Medlar tree 4. The Medlar of Naples 5. The Nettle tree 6. The Pishamin or Virginia Plumme 7. The Cornell Cherry tree From Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris by John Parkinson (Getty Research Institute)

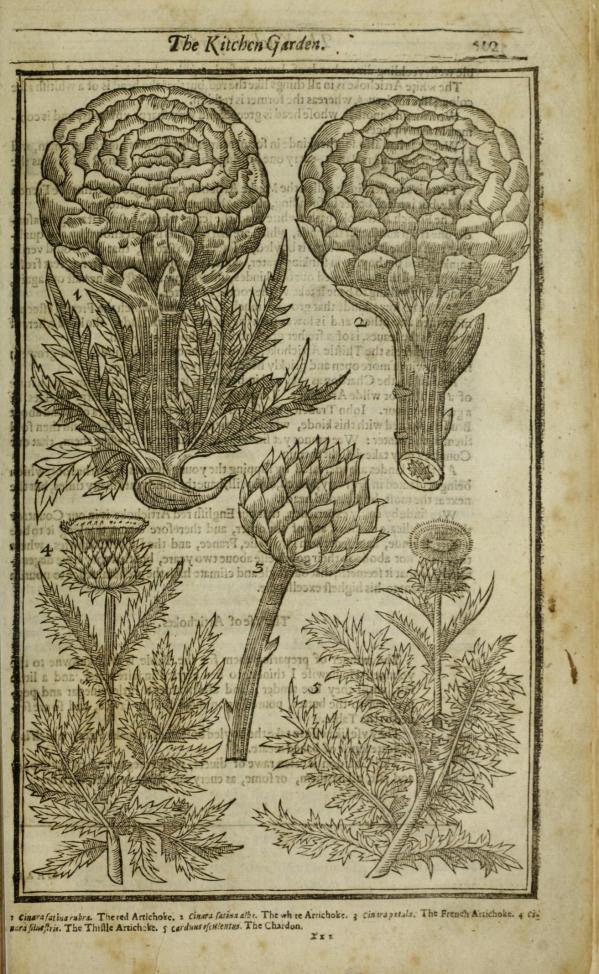

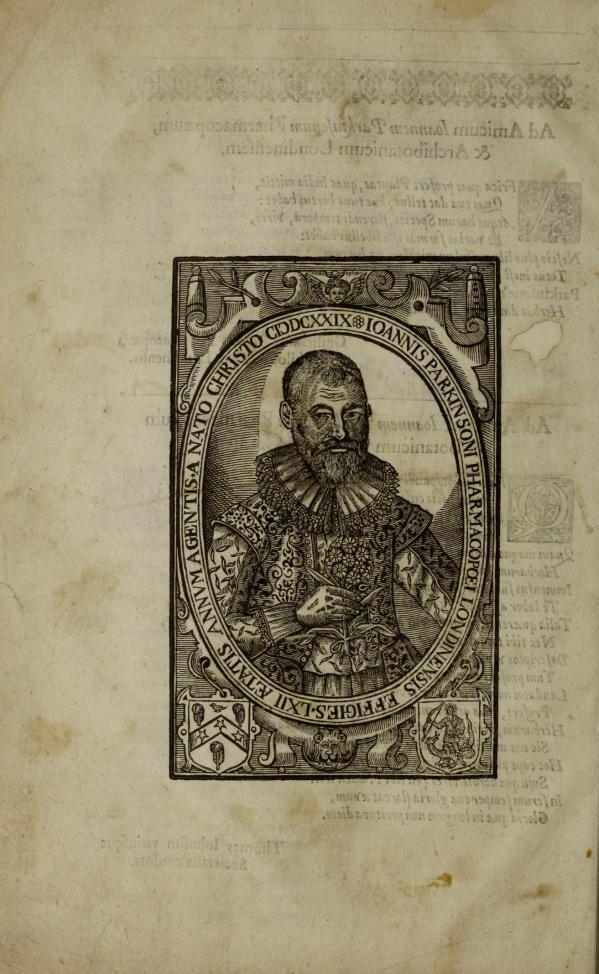

It’s astonishing to see, in the section devoted to the orchard in John Parkinson’s horticultural reference book Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629), the wide range of fruits available in England in the early 17th century. Some of these, such as apples, pears, plums and even quinces are familiar to us – but others like Cornelian cherries, medlars and service berries are no longer grown so widely, or seen for sale today.

Alongside his notes about cultivation, Parkinson also records how these fruits were prepared and processed both for use in the kitchen, and for medical purposes. As a founder member of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, Parkinson was well placed to advise on issues of health. His detailed notes are a reminder of the importance of the garden as a source of medicine, as well as sustenance.

John Parkinson’s botanical garden in Long Acre, close to Covent Garden, has long since disappeared beneath modern London. But the combination of these coloured woodcuts, mostly by the German artist Christopher Switzer, and Parkinson’s own observations about the plants he collected and grew there, brings his garden to life again.

Here follow just a few examples of ‘fruitbearing trees and shrubbes’ known to Parkinson, taken from the Getty Research Institute’s digitised version of the book with its spectacular coloured illustrations.

1. The true Service tree 2. The ordinary Service tree

Parkinson notes that two varieties of service tree, a close relation of the rowan, were considered to have berries that were edible and were cultivated in orchards. According to Parkinson, the ‘ordinary Service tree’ was introduced by John Tradescant and bears fruits shaped ‘some round like an Apple, and in others a little longer like a Peare’. These fruits are ‘mellowed’, like medlars, before eating:

‘They are gathered when they growe to be neare ripe (and that is never before they have felt some frosts) and being tyed together, are either hung up in some warme room, to ripen them thoroughly, that they may bee eaten or, (as some use to doe) lay them in strawe, chaffe, or branne to ripen them.’

7. The Cornell Cherry tree

The Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), or Cornell tree as Parkinson calls it, is shown both bearing fruit and a cluster of small, yellow flowers which appear in early spring. He records that the cherries are popular when in season, but appears not wholly convinced as to their flavour:

‘the fruit are long and round berries, with the bignesse of small Olives, with an hard round stone within them, like unto an Olive stone, and are of a yellowish red when they are ripe, of a reasonable pleasant taste, yet somewhat austere withall.’

1. The small blacke Grape 2. The great blew Grape 3. The Muscadine Grape 4. The burler Grape 5. The Raysins of the sunne Grape 6. The Figge tree 7.

These splendid bunches of grapes represent just a fraction of the varieties known to cultivation in England the early 17th century. Parkinson records that his friend, John Tradescant has twenty varieties growing in his Lambeth garden, but cannot put a name to all of them. As an apothecary, Parkinson mentions multiple uses for products derived from the vine in the treatment of illness, from wine, to vine leaves and raisins:

‘Wine is usually taken both for drinke and for medicine, and is often put into sawces, broths, cawdles and gellies that are given to the sicke. Also into divers Physicall drinkes to be as a vehiculum for the properties of the ingredients.’

‘The greene leaves of the Vine are cooling and binding, and therefore good to put among other herbes that make gargles and lotions for sore mouths. And also to put into the broths and drinke of those that have hot burning feavers, or any other inflammation.’

Parkinson reports that raisins and currants were imported into England in huge quantities, to be used in cooking and eaten on their own, and that the producers of these dried fruits were amazed at how many were consumed. He says that the evocatively named Raysins of the Sunne ‘are the best dryed grapes, next unto the Damasco, and are very wholsome to eate fasting, both to nourish, and to helpe loosen the belly.’

1. The Quince tree 2. The Portingall Quince 3. The Peare tree 4. The Winter Bon Chretien 5. The painted or striped Peare of Jerusalem 6. The Bergomot Peare 7. The Summer Bon Chretien 8. The best Warden 9. The pound Peare 10. The Windsor Peare 11. The Gratiola Peare 12. The Gilloflower Peare

Today, we enjoy the smell of quinces and it’s noted how the perfume from one fruit can fill a room. Parkinson also remarks on this feature of the quince, but interestingly the ‘strong heady sent’ he records is considered ‘not wholsome, or long to be endured’. However, he reveals great enthusiasm for the quince as a culinary ingredient which is eaten raw when ripe, pickled all year round, baked as a ‘dainty dish’ and preserved as ‘Marmilade, Jelly and Paste’. He also records quinces preserved in sugar which were given as gifts:

‘.. being preserved whole in Sugar, either white or red, serve likewise, not onley as an after dish to close up the stomacke, but is placed among other Preserves by Ladies and Gentlewomen, and bestowed on their friends to entertain them, and among other sorts of Preserves at Banquets.’

At his time of writing, Parkinson records six types of quince grown in England – but the varieties of pear far exceed this. As ever, in this period, there is an overlap between the nutritional and medical value of both quinces and pears, which Parkinson says are the only two fruits that should be eaten by people who are unwell:

‘And indeede, the Quince and the Warden are the two onely fruits are permitted to the sicke, to eate at any time.’

As well as being eaten fresh, pears were dried, baked and roasted, and the juice of ‘choke pears’ which were too bitter to eat, made into perry.

In the final pages of his book, a useful index matches medical symptoms with plant remedies, and supplies other information, such as recipes for making colour dyes and keeping garments free from moths.

There’s a link to Parkinson’s text below – a treasure trove for anyone interested in the uses of plants, and the systems of medical beliefs in 17th century England.

A Table of the Vertues and Properties of the Hearbes contained in this Booke

Further reading:

Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, or, A garden of all sorts of pleasant flowers: which our English ayre will permitt to be noursed up: with a kitchen garden of all manner of herbes, rootes & fruites for meate or sauce used with us; and, an orchard of all sorte of fruitbearing trees and shrubbes fit for our land; together with the right orderinge, planting and preserving of them and their uses and vertues (1629) John Parkinson

– digital version from Getty Resarch Institute here

John Parkinson on Wikipedia here