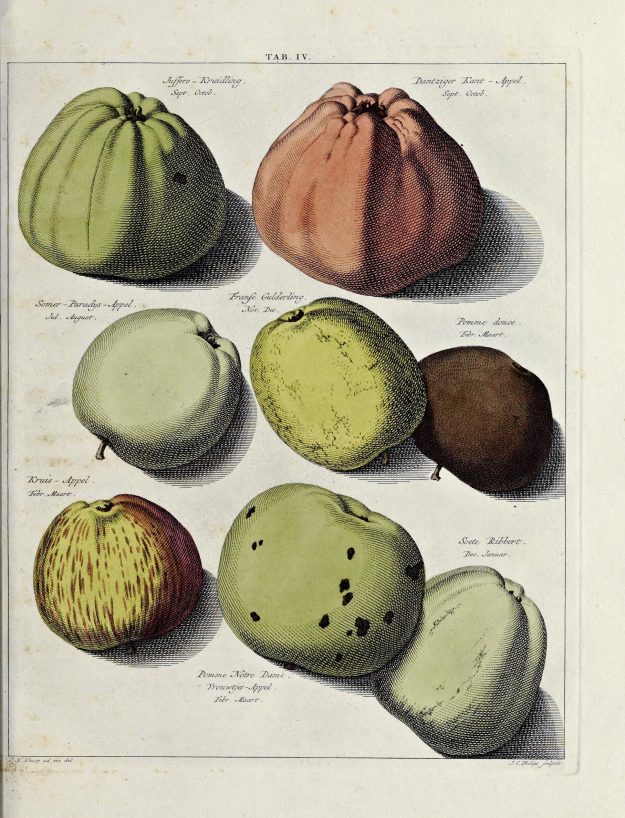

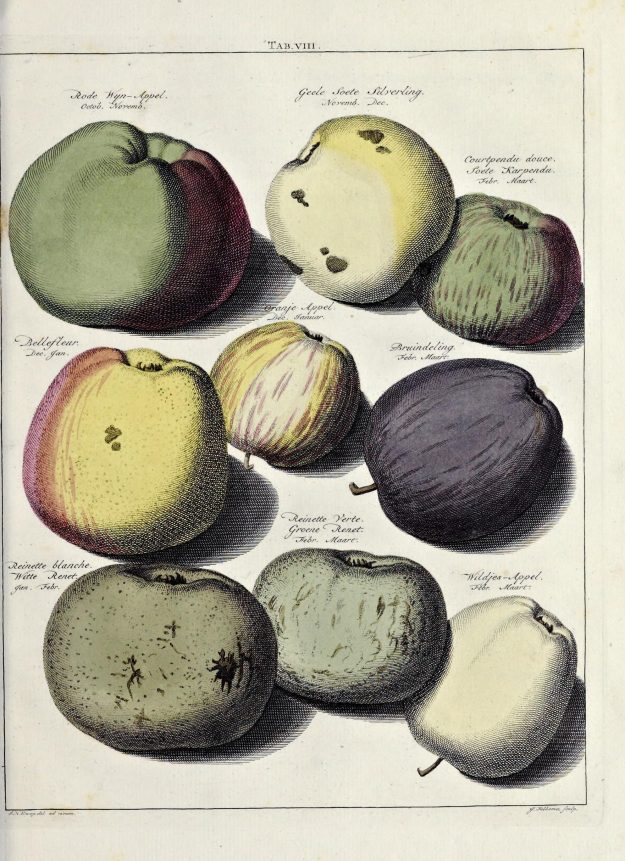

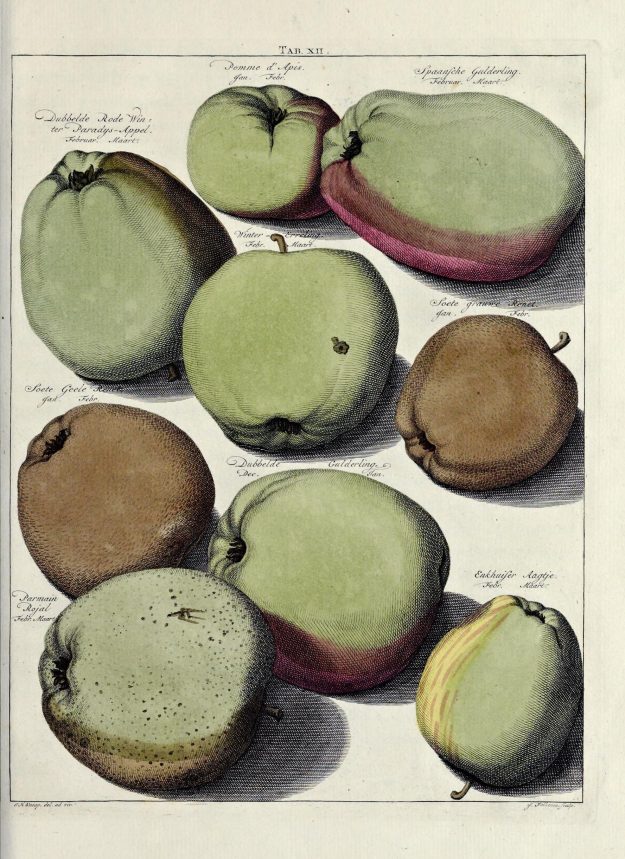

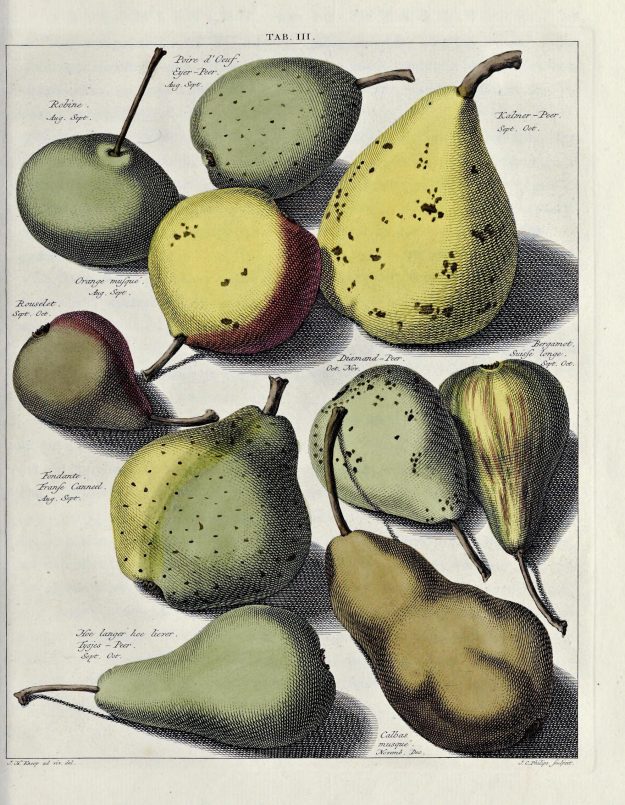

Pomologia, dat is, Beschryvingen en afbeeldingen van de beste soorten van appels en peeren by Johann Hermann Knoop. (1758) Pomologia, that is, descriptions and pictures of the best varieties of apples and pears (The Getty Research Institute via archive.org)

Caroline d’Angleterre, Witte Ribbezt, Spaansche Guelderling, Peppin d’Or, Calville Blanche d’Hyver – what do these names have in common? All are European apples, grown in the mid-18th century and recorded by Johann Hermann Knoop in his spectacular book, Pomologia, that is, descriptions and pictures of the best varieties of apples and pears (1758).

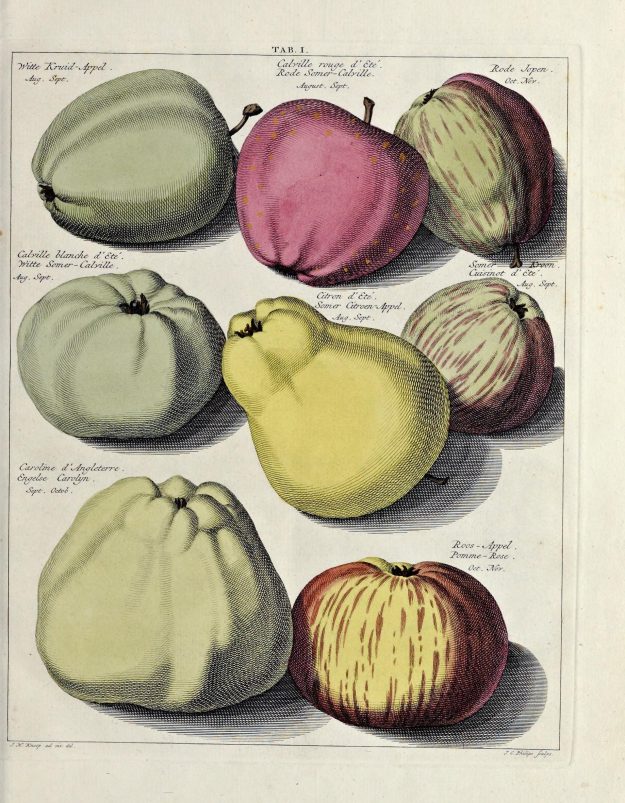

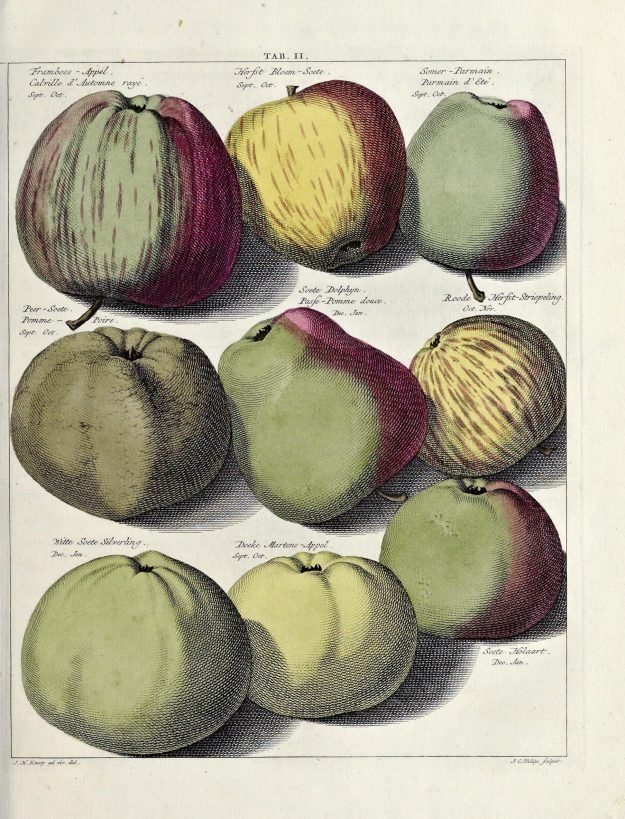

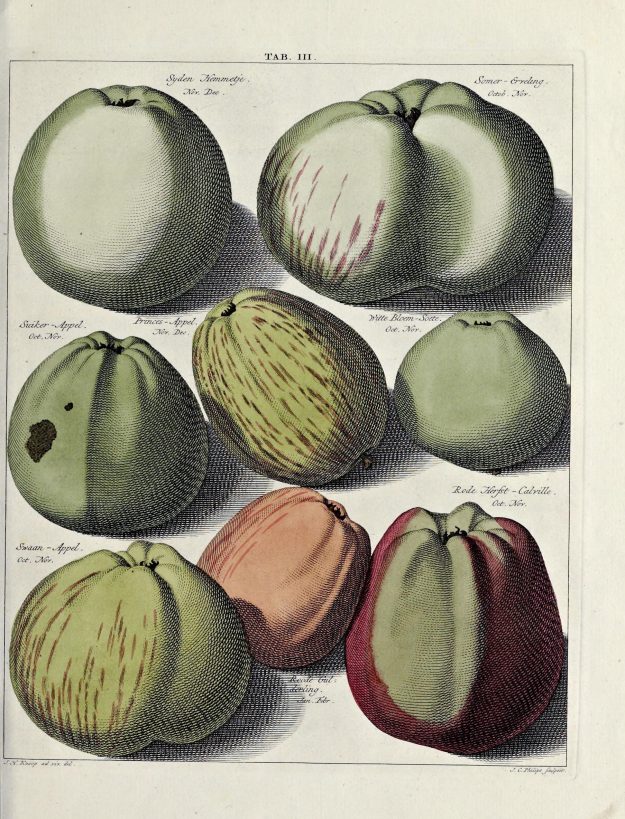

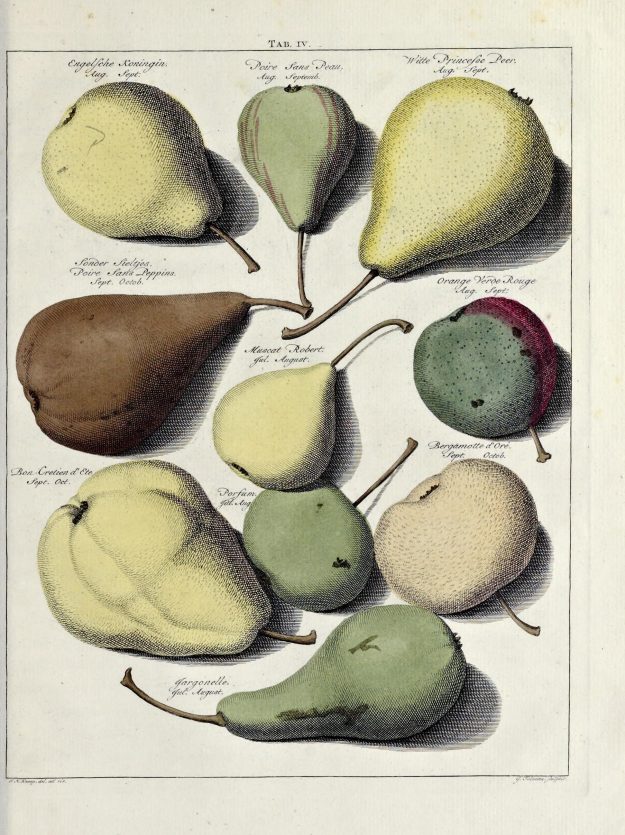

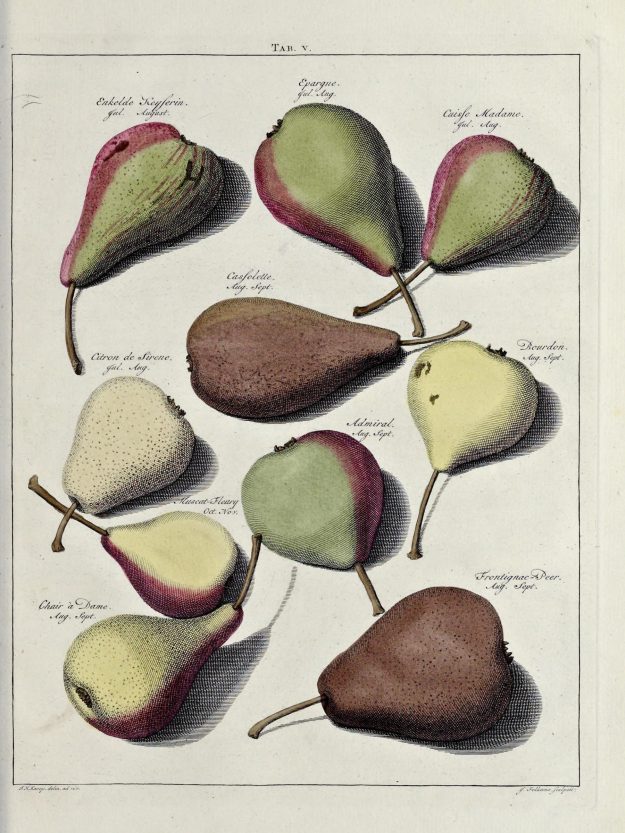

Exceptional coloured engravings reveal the immense variety in the shapes, scale and colour of these fruits. Some of the apples have elongated shapes like plums or melons, looking quite different from those available today. Others, like the Bruindeling and Reinette de Montbron, are exceptionally dark shades of brown, while the skin of the Reinette Grise appears to have a slightly rough texture, as well as its unusual colouring.

The pears are just as diverse. Some, like the Bergamotte d’Oré and another, simply named Parfum, are small and round like apples. Bourdon and Muscat-Fleury are conventionally pear shaped, but miniature. The appropriately named Grande Monarche is a huge green pear, with a touch of redness on the side of the fruit that was exposed to the sun while growing on the tree, and ready to eat in February and March.

Born in Germany, Knoop (early 18th century – 1769) followed his father into horticulture and began his career as gardener at Marienburg, near Leeuwarden in The Netherlands. By 1747 the estate had lost its status as a royal residence, and not long after this Knoop left his position there, with a suggestion that alcoholism might have been a factor in the termination of his employment.

Whilst still at Marienburg, Knoop’s interest in science resulted in his first publication in 1744 – an update of an existing handbook for engineers and surveyors – but it was the publication of Pomologia in 1758 that brought him wider recognition. After Pomologia Knoop published Dendrologia (about garden trees) and Fructologia discussing fruit trees such as cherries and plums, and these three publications were sometimes sold bound together as an encyclopedia. Reflecting Knoop’s breadth of interests, further books on subjects as diverse as heraldry and architecture followed.

Knoop’s ambitious survey of apple and pears covers varieties from the Low countries, Germany, France and England. Information about each of these is organised in chapters to accompany the numbered plates, and includes details of the size and vigour of the trees as well as the relative merits of the fruits, such as flavour and keeping qualities – especially important before modern refrigeration. It also served as an identification manual for readers to match fruits from their gardens to illustrations in the book.

According to the university of Utrecht, the engravings for Pomologia produced by Jacob Folkema and Jan Casper Philips were hand coloured by the daughters of the publisher, Abraham Ferwerda. The skillful use of shading in the engravings conveys a sense of weight and solidity, while the depiction of irregularities and blemishes on the skins of the fruits lends both charm and a sense of authenticity.

Are any of the apples and pears from Knoop’s work still cultivated today? A brief search reveals the apple Calville Blanche d’Hiver for sale at specialist growers Bernwode Fruit Trees. Bernwode notes the cooked fruit keeps its shape and that, ‘Victorian gardeners grew the trees against a wall or under glass, for the best flavour and because chefs valued the fruit so highly.’ Calville Blanche d’Hiver can also be used as dessert apple. The pear Jargonelle is available, and the Poire d‘Angleterre, or Engelse Beurré, with its reddish-brown skin, the flavour described as ‘melting, very juicy flesh, sweet and rich’.

Links to Pomologia (1758) and a French translation (1771) below, plus links to the universities of Delft and Utrecht for biographical information about Knoop published on their websites.

Calville Blanche d’Hyver is the green apple at the bottom right of the page.

The pear Jargonelle is seen at the bottom of this page.

The beautiful brown Poire d’Angleterre appears at the top right of this page

Further reading:

French translation published in 1771 Pomologia (1771)

Biography of Knoop from University of Utrecht

Discussion of Knoop’s career from Prof Cor Wagenaar, University of Delft