Dame Truelove’s Tales by Elizabeth Semple (1817)

My previous post considered gardens as described and illustrated in children’s literature from the early 19th century. I found so many examples, I’ve decided to continue the theme, this time focusing on three books where children are depicted as active gardeners, encouraged by their parents and sometimes by the family’s gardener.

These ‘realistic’ stories with characters and events drawn from daily life are interwoven with messages concerning conduct of life. This development of domestic realism follows a similar pattern to that in adult fiction in the early nineteenth century, with the novels of Jane Austen being the most obvious example. In all these accounts, acquiring an understanding of gardening and the cultivation of plants is valued as a positive and productive way for children to spend their time, and children are often given a section of ground to cultivate for themselves as a reward for good behaviour.

Caroline, in Dame Truelove’s Tales is the youngest of the child gardeners. Pictured above with a little garden rake and a watering can, she asks her father for a garden of her own. Caroline and her three siblings share an area of ground where they practice gardening, but she has become frustrated with this arrangement, as her brothers and sisters show no aptitude for the activity and, worse, they are causing damage to her own efforts:

Dame Truelove’s Tales by Elizabeth Semple (1817)

Caroline’s wish is granted and the next day she finds an area has been planted with shrubs and flowers by Nicholas, the family’s gardener. Caroline will weed and water the garden and Nicholas will help her with tasks she is not yet strong enough to do herself.

In The Gardeners from The Keepsake; or, Poems and Pictures for Childhood and Youth, four children are pictured carrying tools in readiness to start their work in the garden.

To the garden we will go,

Take the rake, the spade, the hoe,

Dig the border nice and clean,

And rake till not a weed be seen.

Then our radish-seed we’ll sow,

And mignionette, a long, long row,

And ev’ry flowret of the year,

Shall have a place of shelter here.

The poem goes on to describe the children growing flowers to decorate a maypole for the May Day celebration.

The Keepsake; or, Poems and Pictures for Childhood and Youth (1818)

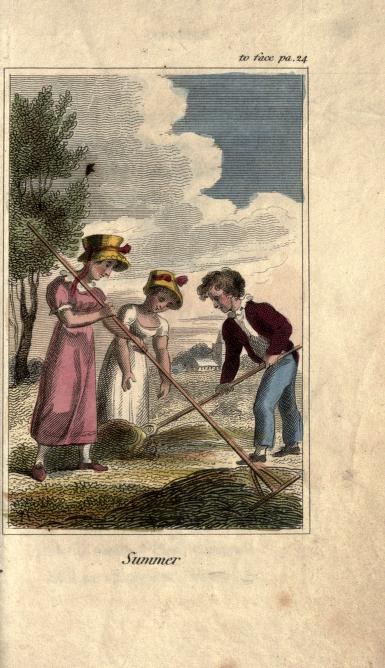

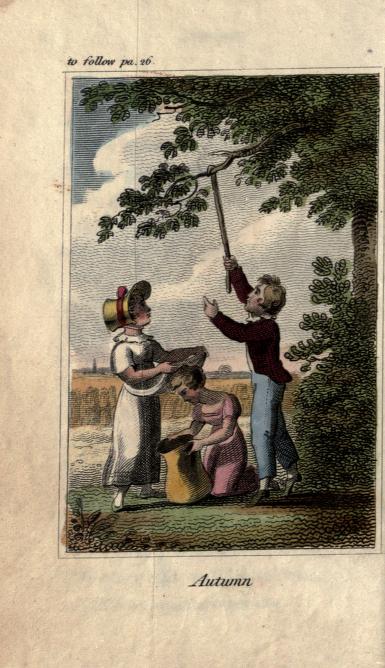

Also from The Keepsake, is a series of poems about the four seasons. In Summer children are pictured helping to spread freshly mown grass to dry in a hay meadow, and in Autumn they harvest hazel nuts from the woods. The poems with their description of the weather, plants and the seasonal activities that are going on in the surrounding countryside convey a connection to the landscape and nature which seems sadly remote from what many of us experience today.

The Keepsake; or, Poems and Pictures for Childhood and Youth (1818)

Long and thick the grass is grown,

Ready for the mower’s care,

When his scythe has laid it low,

To the hay-field we’ll repair.

Each shall have a fork and rake,

To spread it widely to the sun:

Many hands together join’d,

Make the labour quickly done.

The Keepsake; or, Poems and Pictures for Childhood and Youth (1818)

When Maria’s task is done,

We will to the nut-wood go;

Each a bag and hooked stick,

Down to pull the cluster’d bough.

Oh! How tempting ripe they hang:

Softly, softly pull them down,

Lest the bright, brown nuts should fall,

And leave the empty husk alone.

Bags and pockets all are full,

And evening says we must not stay;

With heavy loads we’ll hasten home,

And come again another day.

The Juvenile Gardener. Written by a Lady, for the use of her own children with a view of giving them and early taste for the Pleasures of a Garden, and the Study of Botany (1824)

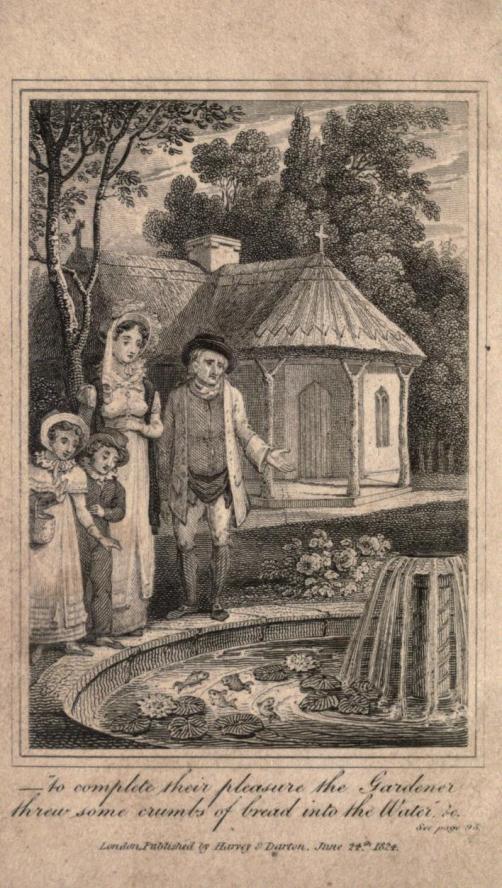

As a shallow kind of person, I was initially rather disappointed with The Juvenile Gardener as it contains only one black and white illustration (in contrast to other books from this period, with their numerous colour plates). Also, the children Frank and Agnes Vernon, and the narrator herself, are depicted as such paragons they are not wholly believable. However, for anyone interested in the history of English gardens, these are evocatively described by the knowledgeable author.

Two gardens feature in the story, the first located in the north of England where the family live, and the second is Seaview in Hampshire, which belongs to an uncle. Here is a description of the flower garden at Seaview as it appears in late summer:

The smooth lawn, the numerous flower-beds, of different forms; the stages of hardy green-house plants, brought here for the summer; the trellis covered with roses and carnations; – all combined to form a scene of great beauty. ..But what pleased them most was a walk from the flower-garden to a summer-house, on each side of which was a hedge of dahlias, of every colour and shade in full bloom.

As Frank learns to appreciate gardens by means of practical experience in his own section of the family garden, Mrs Vernon teaches both children about botany and wild flowers. She mentions William Curtis’s Flora Londinensis as the best book to consult on the subject and recommends Sowerby’s British Botany and Curtis’s Botanical Magazine for images of exotic plant introductions.

The gardeners employed by the families are both characters in this narrative. The Vernon’s gardener William has the task of planting a garden for their son Frank in the spring, and chooses annual flowers and vegetables that will produce a quick and satisfying result for a young child. He also teaches Frank about weeds, how to take cuttings of herbs and to recognise the seeds of vegetables and flowers.

Maclaren is the gardener at Seaview, in Hampshire, who is pictured in the book’s one engraving (above) feeding goldfish with Mrs Vernon and her children. We learn that he was so upset by a former employer’s ten children wreaking havoc in the garden, that he resigned his post – and he is suspicious of Frank and Agnes until he realises they can be relied on to behave themselves outdoors.

But the most remarkable garden they visit (in spite of being the least grand) comes at the end of their visit to Hampshire when the children visit a ship of war. Unlikely as it seems, the midshipmen have planted a garden on board the ship:

Frank smiled when they took him to a gallery outside the cabin-windows, to see their garden, which consisted of some large boxes filled with earth, in which grew some lettuces, radishes, and cabbages, which were not in the most flourishing state; but Frank was convinced, that on a long voyage, even these vegetables would afford a treat to those who could not procure better.

If ever there was a garden asking for a picture, it must be this one?

Links: all texts available via archive.org