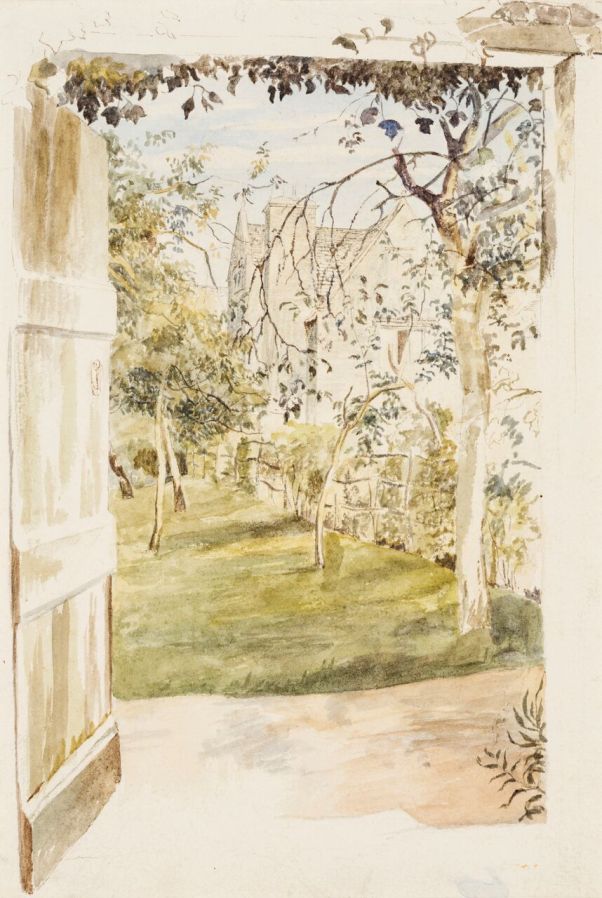

Lytes Cary Manor, Somerset managed by the National Trust

Somerset is blessed with many beautiful houses and one of the most charming must be Lytes Cary Manor, not far from the town of Somerton. Surrounded by farmland, this handsome building, parts of which date back to medieval times, sits peacefully in the evocative landscape of the Somerset Levels.

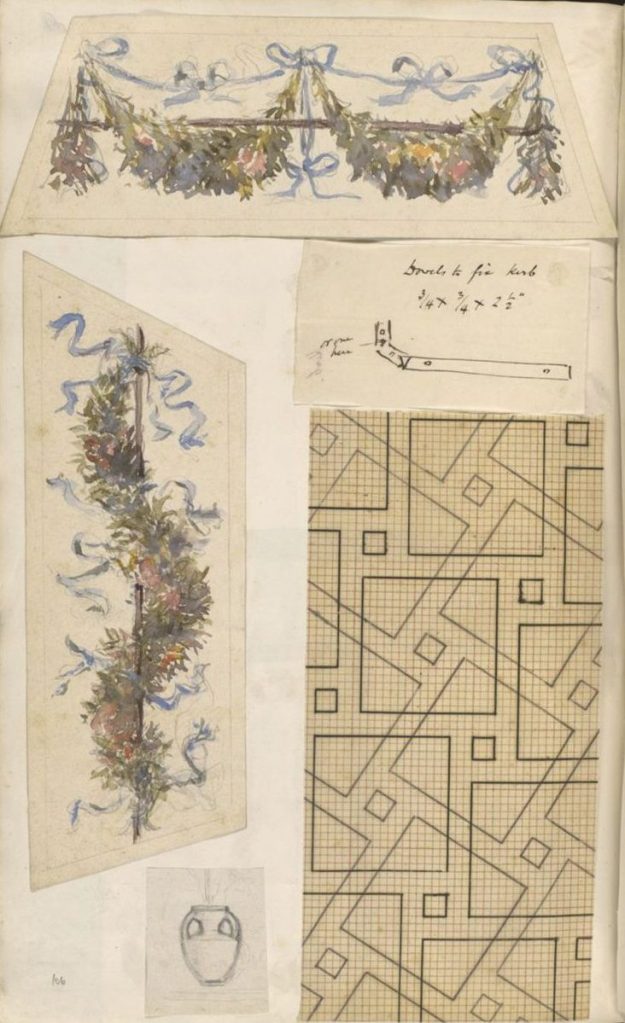

Occupied by the Lyte family for four centuries, the great hall was built in the 15th century, followed by further additions in the 16th and 17th centuries. The family eventually sold the house in the mid-eighteenth century owing to financial difficulties and after being used as a farmhouse and barn for a time, the buildings fell into disrepair. Bought by Sir Walter Jenner in 1907, the house and garden were developed in the Arts and Crafts style by the architect C E Ponting. Sir Walter Jenner passed the house to the National Trust in 1948.

Laid out in classic Arts and Crafts style, the Grade II listed gardens are arranged as a series of rooms, divided by formal yew hedges and connected by pathways of local lias stone. At the front of the house, through the imposing gateway, the central path is flanked by a series of yew topiary forms, known as the twelve apostles. Either side of the entrance, a cloud pruned box hedge is kept just above the level of the wall, while a row of enormous topiarised box forms seem to process along an adjacent wall towards the tiny chapel, thought to have been built around 1343 and the earliest building on the site.

Speaking briefly to head gardener Sam Hickmott, he explained that they were updating some of the non-structural planting close to the chapel and the house, introducing light tones and airy forms to soften the formality created by the expanse of topiary in this part of the garden. This approach is evident throughout the garden, with great care taken in the choice of perennial cultivars, ensuring their colours harmonise with those of the house.

In the main border, generous clumps of phlox, asters and golden rod recall the abundant planting style of the Edwardian period and some of their favoured plants. Using a combination of these perennials, together with modern introductions like Salvia ‘Amistad’ and Hydrangea ‘Annabelle’ creates the spirit of a traditional border, but with a subtle nod to contemporary garden fashions.

Steps down to the West Terrace garden reveal a burst of jewel colours with dahlias, veronia and Nicotiana x hybrida, ‘Tinkerbell’, with tiny flowers somewhere between maroon and terracotta. Here, the pathways contain four beds of creeping thyme, forming a low, green carpet and views of the surrounding landscape can be glimpsed through a wrought iron gate in the yew hedge.

Yellow is a colour that divides some in the world of gardening, but is used here to great effect. From the brighter tones of rudbeckias and heleniums to kniphofias, Clematis rehderiana and coreopsis in the palest shades of yellow, all seem to enhance each other and blend with the golden hamstone framing the windows and doorways of the building. This creates a sense of unity to the planting and echoes the yellow wildflowers like agrimony and common fleabane growing in the hedgerows on the wider estate.

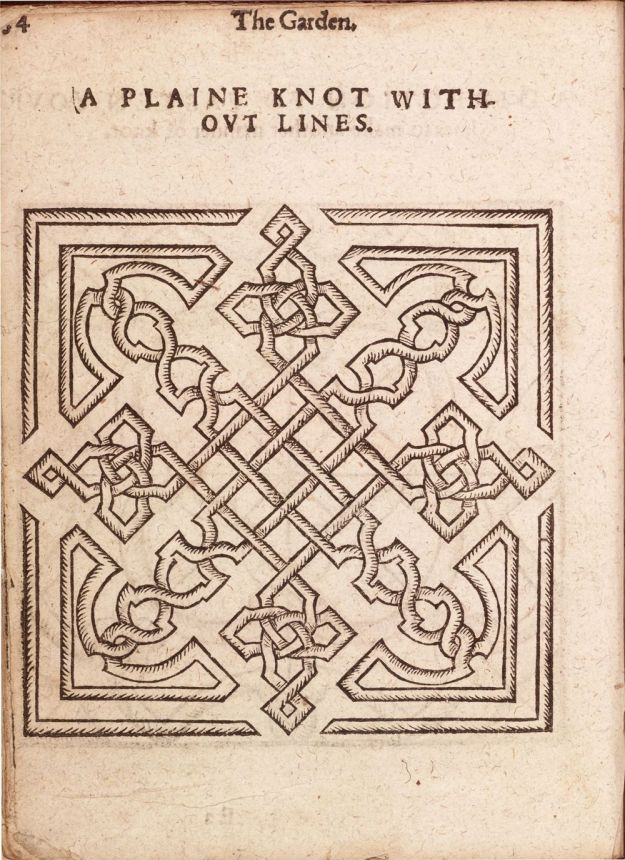

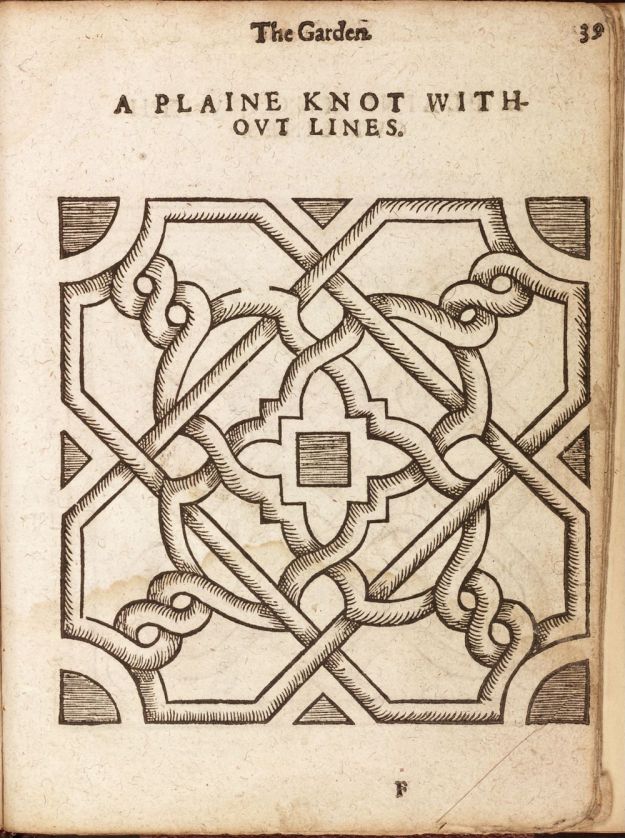

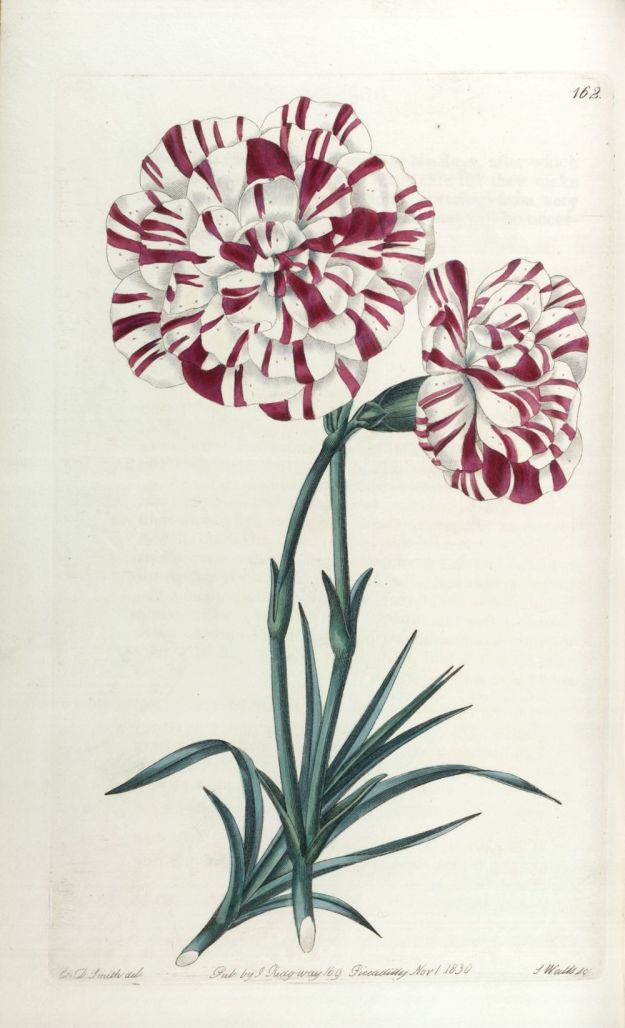

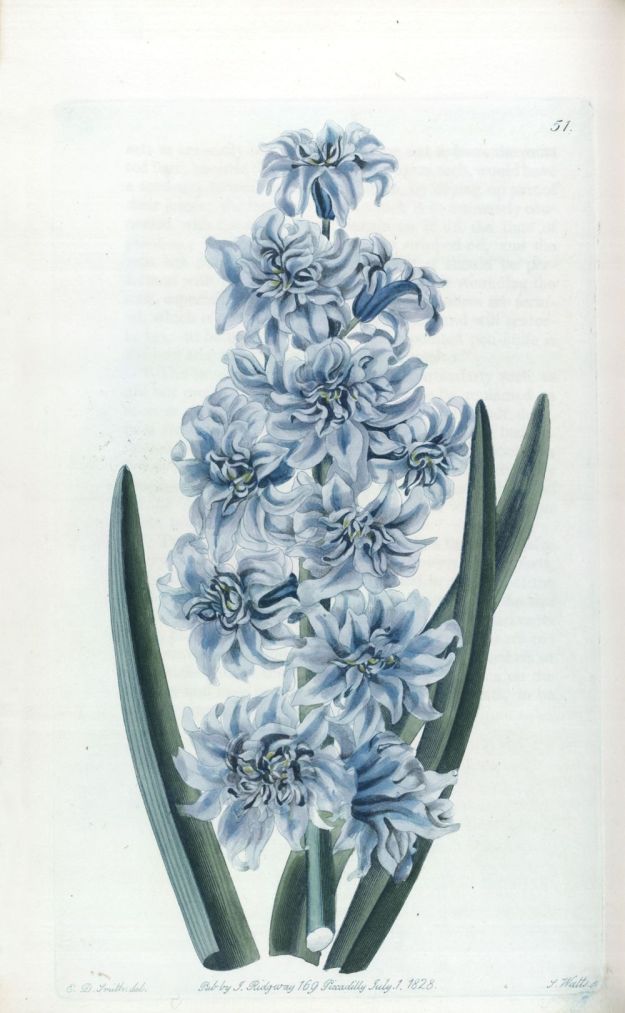

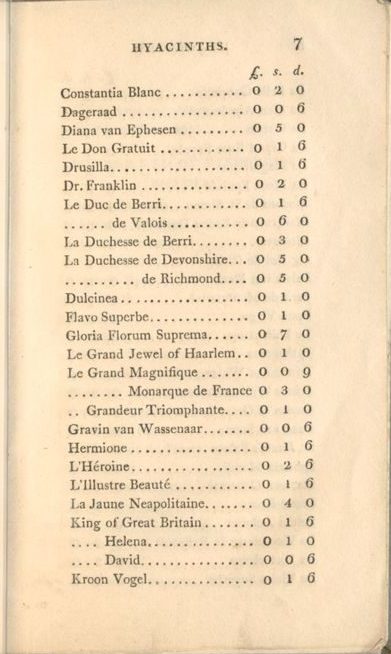

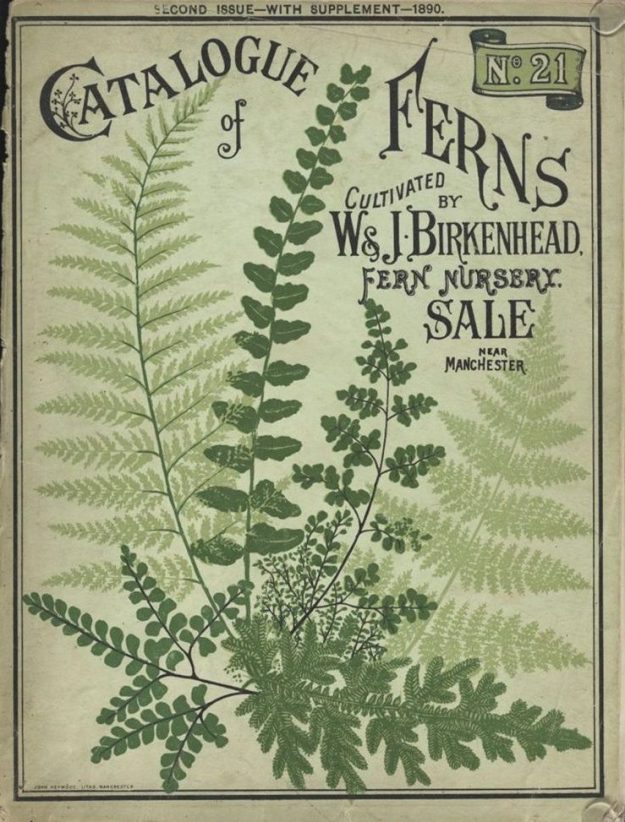

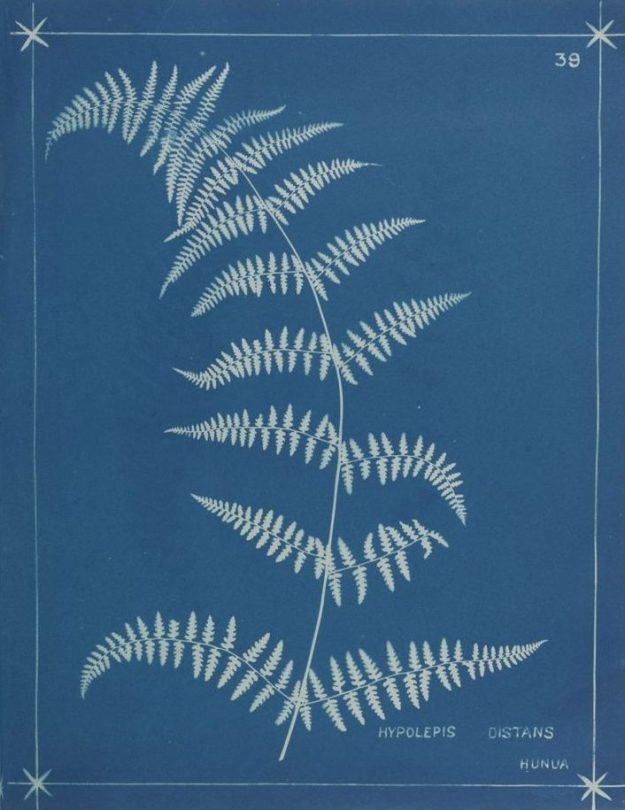

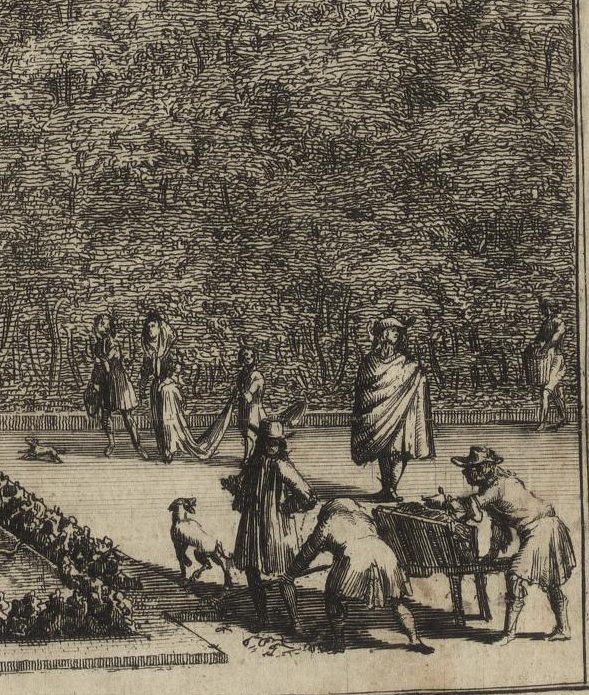

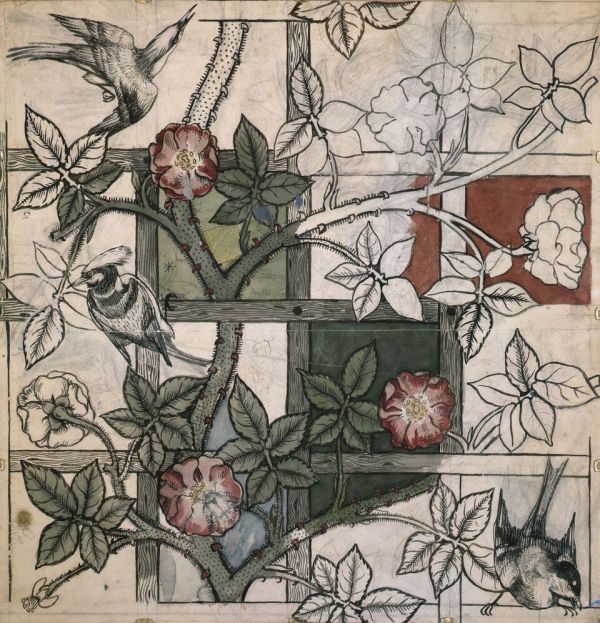

Although there’s no herb garden at Lytes Cary, herbs are used liberally in the planting. This seems especially appropriate here, as former resident and Oxford educated scholar Henry Lyte (1529 – 1607) produced one of the great 16th century botanical publications whilst living at Lytes Cary. Published in 1578, A Niewe Herball was Lyte’s English translation of Cruydeboeck written by the celebrated Dutch physician Rembert Dodoens in 1554. Illustrated with over 870 woodcuts, the book details the cultivation requirements and medicinal properties of an array of plants known in this period, from herbs, trees, bulbs, food crops and weeds.

Cruydeboeck had been translated into French by Charles de L’Ecluse in 1557, and it was this version that Lyte used for his English translation. There’s a small portrait of Henry Lyte in the house, alongside a first edition of his book, although his important contribution to English horticulture is slightly eclipsed by stories of the Jenners’ more recent residency.

Back in the garden, the sections furthest from the house contain orchard trees including apples, pears and quince, a separate cherry orchard, a lavender garden and a croquet lawn. The pathways, lawns and hedges connecting these spaces are beautifully maintained by the gardening team, which is no mean feat in a garden of five acres, and whilst also looking after the National Trust’s Tintinhull gardens a few miles away.

This quietly spoken house with its atmospheric garden is well worth a visit. Links to further information about Lytes Cary Manor below.

The main border

White themed section of the main border

Bay window, with John Lyte’s coat of arms

Pale yellow verbascum

Yellow and white kniphofia with Doellingeria umbellata (formerly Aster umbellata)

Clematis rehderiana and a yellow leaved jasmine cover this stone archway

Clematis rehderiana with Hydrangea aspera

West terrace and garden

Four symmetrical beds containing species of creeping thyme form a strong feature in the West Terrace

Tall stems of purple flowered veronia

The garden is full of pollinating insects

Tansy, or Tanacetum vulgare

Yew and box topiary at the entrance to the house, with the water tower in the distance

Cattle on the estate taking shelter from the sun under the boughs of a tree. They browse the lower leaves of the trees, raising the crowns slightly to exactly the same level, giving a coherent look to the parkland.

Further reading:

Lytes Cary Manor on Wikipedia here

Henry Lyte on Wikipedia here

National Trust Lytes Cary Manor here

A Niewe Herball, or Historie of Plantes at the Wellcome Library here