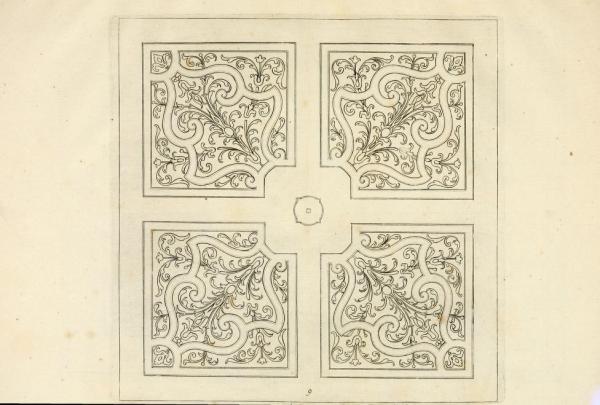

Plant de géranium rouge Photographs by Eugène Blondelet courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Perhaps it’s in February, at the very end of the winter, that we look forward to the summer months with the most intensity? These autochrome photographs, taken by Eugène Blondelet sometime between 1907 and 1920, provide a welcome reminder of warmer days ahead and capture perfectly the pleasures of long, sunny days outside in a French family garden.

The autochrome colour photography process was created by the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière in the early 1900s and they launched Autochrome Lumière in 1907, aimed at the amateur photographer. Their process involved the use of prepared glass plates with tiny grains of dyed potato starch pressed onto one side and photosensitive silver halide emulsion on the other. Autochrome was too expensive to make colour photography accessible to everyone, but proved popular with photographers who could afford it (like Blondelet), who frequently used the new technology to record their families and domestic surroundings, including gardens.

Autochrome Lumière required long exposures, so a tripod was needed to keep the heavy camera stable and people had to remain still while a photograph was being taken to avoid motion blur. Clearly, the young boys in fancy dress (Garçonnets déguisés dans un jardin) photographed by Blondelet were unable to keep their poses quite long enough for the exposure time required – perhaps the double excitement of dressing up and having their photograph taken made this impossible – but the blurring caused by their movement somehow underlines their youthful energy and adds to the charm of the image.

Autochrome was best suited to objects with a fixed position and plants were ideal subjects for the photographer, being both static and colourful. Images of bright floral arrangements were used by the Lumière Brothers as a means of marketing their process, as they were so effective in demonstrating its ability to replicate colour accurately. Blondelet’s still life photographs of garden flowers reveal an abundance of roses, phlox, dahlias, geums, asters, coreopsis, gladiolus, and crocosmia – some of the popular flowers of the period.

The series of photographs entitled Garçonnets déguisés dans un jardin give us a glimpse into how this example of a domestic garden was planted. The borders behind the children are edged quite formally with three rows of low clipped box with a mass planting of orange French marigolds behind these, providing a continuous block of colour. This effect would be further amplified later in the season by a row of nasturtiums which we can see beginning to climb up the balustrade.

Another (highly staged) image Garçonnets posant dans un jardin shows two boys in the role of gardeners, one with a small rake and the other pulling a wooden cart containing flowers supposedly gathered from the abundant and colourful border behind them. Close up shots reveal a hydrangea, slightly wilted in the heat of the sun, some dahlias and a brilliant red pelargonium.

Blondelet’s interest in gardens seems to have extended beyond his own. Massif de bégonias rouges et plant de bananier shows detail of a summer bedding display which looks typical of those planted in a public park. Jardin d’une propriété en bordure d’un cours d’eau shows the traditional wooden gates, picket fencing and neat planting of a well cared for cottage garden, with steps down to a slow moving expanse of water.

What is the appeal of autochrome photographs today? While their colour has intensity there’s also a slightly diffuse quality to the images, which must owe something to the materials used in the process, especially the granular nature of the potato starch. While unmistakably grounded in the real world, at the same time these images seem to possess a sense of detachment from reality; a dream-like quality. Some of the imperfections and inevitable deterioration of the fragile plates over time contribute to this effect – the colour distortion in Blondelet’s Bouquet des roses from green at the top of the frame to red at the bottom is one such example. But if the world depicted by black and white images can sometimes seem remote, these autochrome photographs connect us with the past with a striking immediacy.

Thanks to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for making these beautiful images available online.

Garçonnets déguisés dans un jardin

Garçonnets déguisés dans un jardin

Garçonnets déguisés dans un jardin

Garçonnets posant dans un jardin

Fleurs de diverses couleurs dans une cruche

Bouquet de roses

Bouquet de fleurs variées blanches

Bouquet composé de fleurs et de brins d’herbe

Fleurs fanées dans un vase

Massif de dahlias roses

Massif ensoleille d’hortensia bleu

Massif de bégonias rouges et plant de bananier

Jardin d’une propriété en bordure d’un cours d’eau

Plant de géranium rouge

Feuillage en contrejour

Autoportrait – Eugène Blondelet

Further reading:

Comprehensive explanation of Autochrome Lumière here

The Photographer in the Garden (2018) Jamie M Allen / Sarah Anne McNear

published by the George Eastman Museum / Aperture – link here

Bibliothèque Nationale de France – online collections here

The story of Auguste and Louis Lumière here