Swift sculpture by Mark Coreth placed in the 200 year old olive tree in the Cloister Garden, at the Museum of the Order of St John

This month I’m bidding farewell to the Cloister Garden at the Museum of the Order of St John in Clerkenwell which I’ve had responsibility for maintaining since 2019. So, one day back in June, I visited the garden with my camera to reflect on the space and the important role it plays in this part of London, where accessible green space can be hard to find.

Entered through an archway on the east side of St John’s Square, the garden is sheltered by walls on all sides, including that of St John’s Priory Church. These walls, together with two enormous plane trees in the churchyard, seem to absorb much of the thundering traffic noise from nearby Clerkenwell Road and establish the garden’s atmosphere of tranquility.

The Priory in Clerkenwell was set up in the 1140s as the English base for the Order of St John. This medieval military Order, also known as the Knights Hospitaller, had its headquarters in Jerusalem, where members provided care for the sick and wounded. Today the Order of St John is best known for the health organisations it continues to run, including the St John Ambulance.

The garden is a paved space and with its formal, symmetrical layout is somewhat reminiscent of a paradise garden, with a series of pathways and narrow beds creating four main areas surrounded by fragrant plants. Developed centuries ago in Iran, this style of Islamic ‘fourfold’ garden, or chaharbagh, became popular in Asia and the Mediterranean.

Western travellers, such as the Knights Hospitaller would have encountered gardens in this style, and over time some elements found their way into European garden design. Water was an essential feature of paradise gardens, and at one time there was a pool at the centre of the Cloister Garden, now replaced with a mature olive tree forming a dramatic central focus. Visitors can still experience the sound of running water, however, from a small fountain located on the north wall of the garden.

Designed by Alison Wear in 2011, the planting uses medicinal herbs like rosemary, lavender, and wormwood, alluding to the medical traditions of the Order of St John, which cultivated these plants for their healing properties. As well as these, Wear has included modern decorative perennial plants like Geranium ‘Rozanne’, Geranium ‘Brookside’, oriental poppies and crocosmia for their succession of attractive flowers. The space also serves as a memorial garden for St John’s Ambulance members associated with the site, whose names are remembered on the walls of the cloister on the east side of the garden and by roses planted in the adjacent raised beds.

Much of the planting is quite low, so that in places visitors can step over the beds conveniently, as well as using the pathways. This aspect of Wear’s design encourages people to slow down, adding to the sense of calm in the space, and seating is provided for those who wish to stay a while. Once seated in the garden, the low planting immediately feels taller, and more immersive, while the formal lines appear looser, especially when looking diagonally across the space.

Our increasingly hot summers in London have been harsh on some of the capital’s gardens, but the Cloister Garden, having a high proportion of plants that come from the Mediterranean region, tolerates the heat well. Indeed, herbs like oregano, hyssop, myrtle and sage, as well as the twin bay trees seem to relish these conditions. The 200 year olive tree, brought here from Jerusalem some years ago, also thrives. While not designed specifically as a wildlife garden, flowers like lavender attract a range of bees and other insects, and birds are regular visitors, especially when the garden is empty of people.

During my maintenance visits, it’s been abundantly clear how much the garden is appreciated by visitors; whether they are local residents, tourists or those who work locally and come to enjoy the outdoor space at lunchtime. Some people have told me that being in the space, even briefly, helps improve their sense of wellbeing. Some like to spend ten minutes of quiet before a long day at the office, while others bring the office to the garden and have their work meetings here. It’s interesting to see how visitors move the lightweight café tables and chairs around to suit the size of their group, or their preference for sun or shade.

One frequent visitor would still come in the early morning to read his book, even in the pouring rain, when he would take shelter underneath a huge golf umbrella. Rachel Job from the Museum told me about a visitor from Puglia who was visibly moved by the health of the garden’s olive tree, as the olive groves in his part of Italy had been ravaged in recent years by Xyella, a bacterial infection. Another local woman would regularly ask after the resident robin that liked to search for food scraps in the garden.

I hope next time you find yourself in Clerkenwell you’ll take a few minutes to visit the Cloister Garden for a moment’s respite from the clamour of London. The Museum of the Order of St John is located at St John’s Gate and hosts exhibitions relating to the long and rich history of the Order. The garden is generally open – closing occasionally for events and workshops – details of opening hours here and more links below:

The olive sits like a tree of life, in its central position in the garden

Peacock butterfly sunning itself on the wall of St John’s Priory church

Hypericum x hidcoteense ‘Hidcote’ often called St John’s wort

Rosa gallica ‘Officinalis’ or the Apothecary’s rose.

Rosa gallica ‘Officinalis’ or the Apothecary’s rose.

Rosa ‘The Generous Gardener’

Rosa ‘St John’ – grown here as a short climber this floribunda rose flowers continuously from May to December.

Flowers of Acanthus mollis and self seeded Digitalis purpurea form pleasing vertical accents. The pink rose is Rosa ‘Gertrude Jekyll’

Further reading:

The history of the Order of St John – Museum website here

The Order of St John Wikipedia page here

Penelope Hobhouse’s Gardening Through the Ages Simon & Schuster (1992)

Article by Andrew Kershman (showing how much the olive tree has grown since 2016) here

RHS on Xyella fastidiosa here

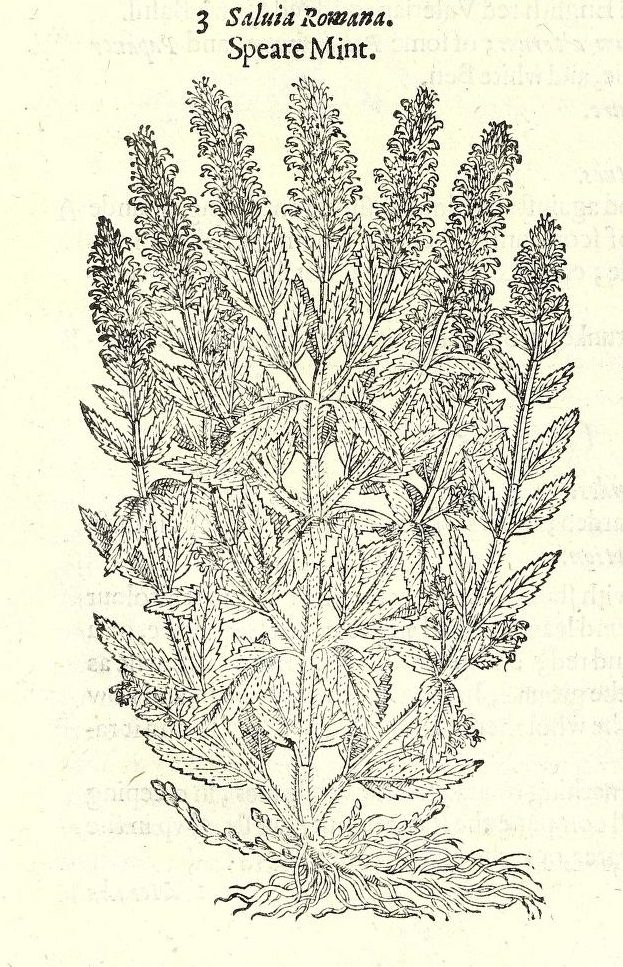

Of Sage.

Of Sage.

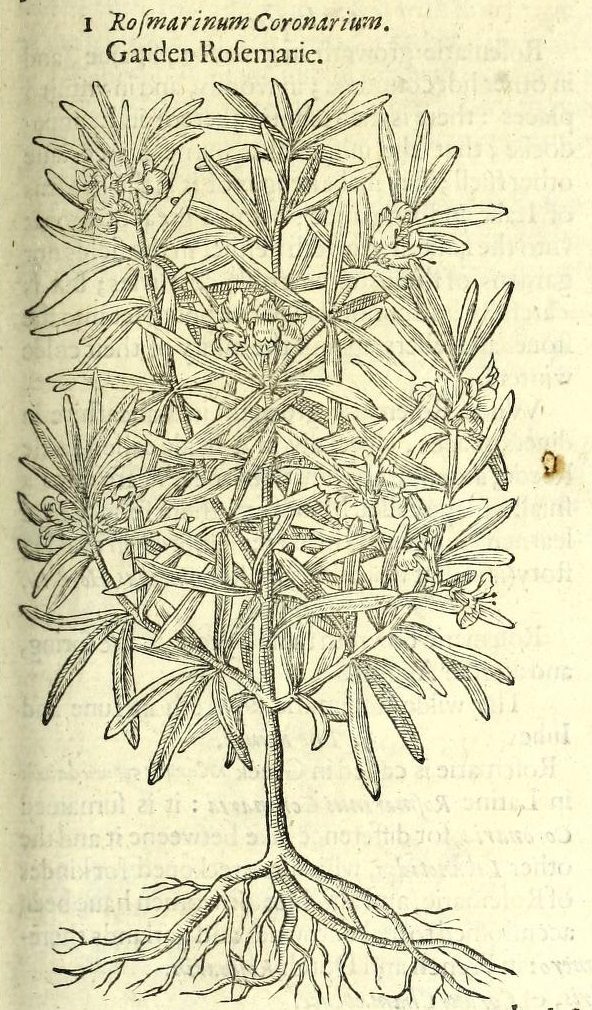

Of Rue, or herbe Grace.

Of Rue, or herbe Grace.