Page’s Champion Auricula from The Florist’s Guide, and Cultivator’s Directory Vol l by Robert Sweet (1827 – 1832) Engraved by S. Watts after an original by Edwin Dalton Smith. All images from RHS Digital Collections

In April this year, the Royal Horticultural Society launched its new Digital Collections platform, with thousands of items from the Libraries and Herbarium now available online to the public for the first time. From an accounts book belonging to landscape gardener Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, to historic nursery catalogues from locations across the UK, many items are unique to the RHS Collections.

Funded by the National Lottery’s Heritage Fund, this is the beginning of a major project that will see further content from the Society’s collection uploaded in the coming months and years. Currently divided into sections for archive, artworks, bookplates, Herbarium specimens, nursery catalogues, photographs and books, there’s already a wealth of material to view.

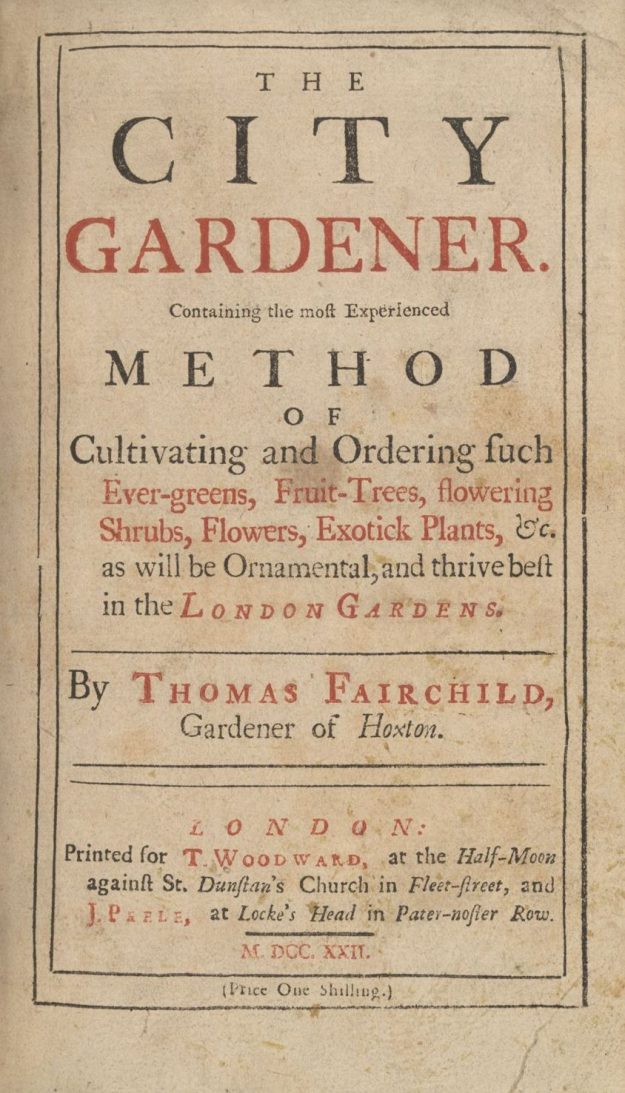

In the books section, the RHS has been strategic in their choice of material to digitise, prioritising those books not already available on other platforms. One of these is The City Gardener (1722) by Thomas Fairchild, a nursery owner in Hoxton, London. Fairchild’s record of plants in cultivation, popular garden styles, and the challenges of growing in the polluted atmosphere caused by sea coal, gives an invaluable insight into the capital and its gardens during this period.

The City Gardener (1722) by Thomas Fairchild

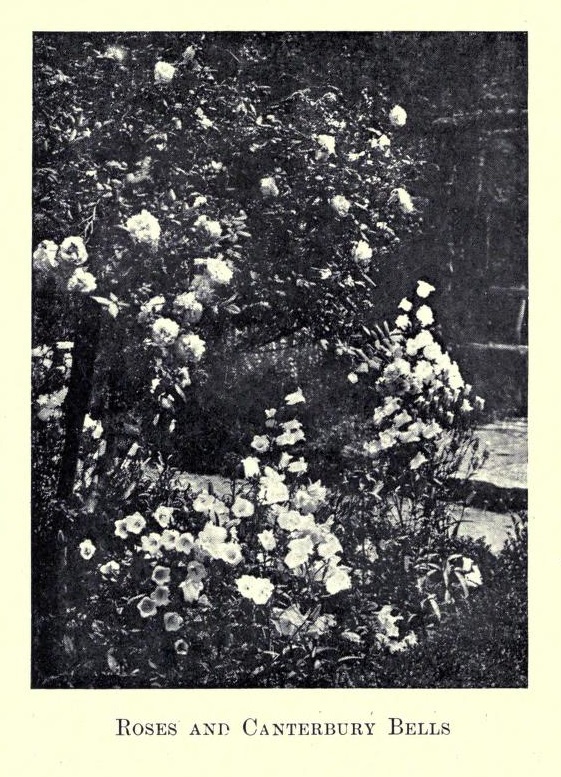

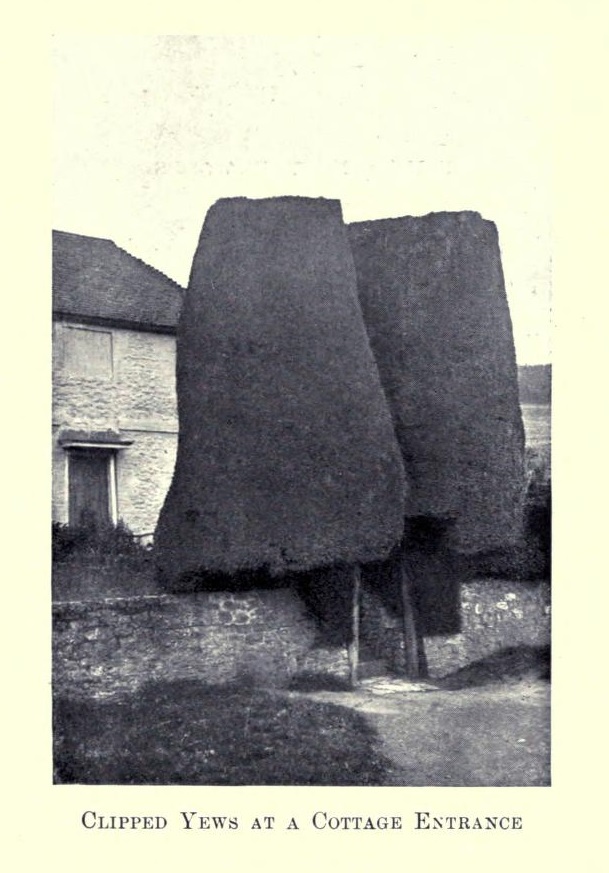

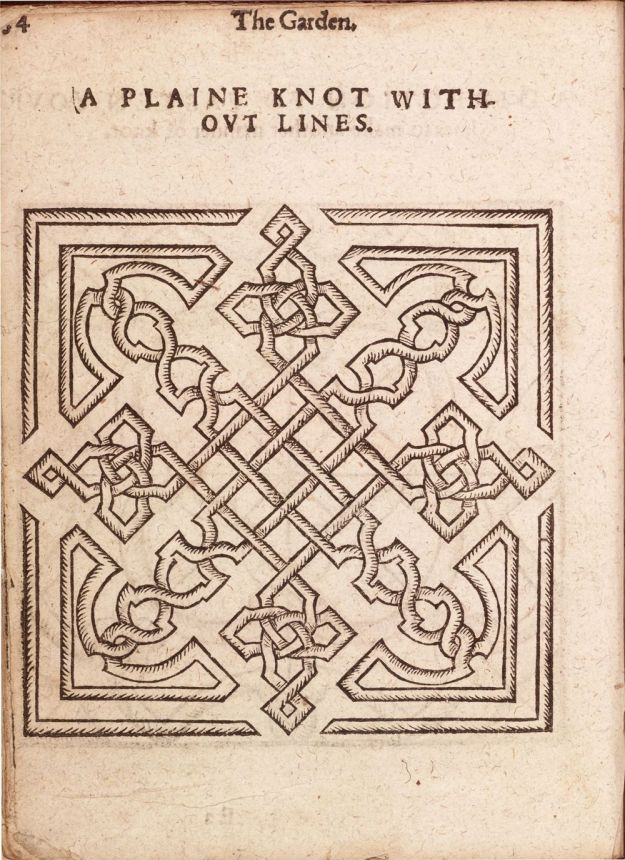

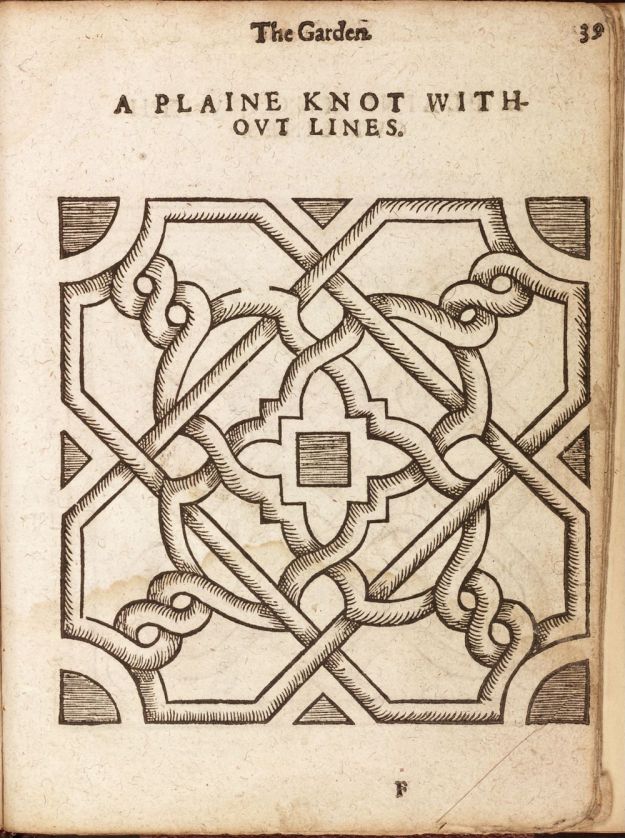

As the name suggests, the bookplates section is comprised of illustrations taken from books in the RHS’s collection. The dislocation of these images from their context does present something of an issue (for me, at least), as some of their meaning is lost. However, the plates are full of interest, and hopefully the books from which they were taken are on the RHS’s list to be digitised in the near future.

This set of bookplates from The Orchard and the Garden, printed by Adam Islip (1602), shows a range of knot garden designs and instructions for laying them out. These delightful, detailed woodcuts remind us of the enthusiasm for pattern, symmetry, and symbolism in the Tudor period. The book must have found a ready audience, as this example is a third edition, the first being published in 1594.

The Orchard and the Garden printed by Adam Islip (1602)

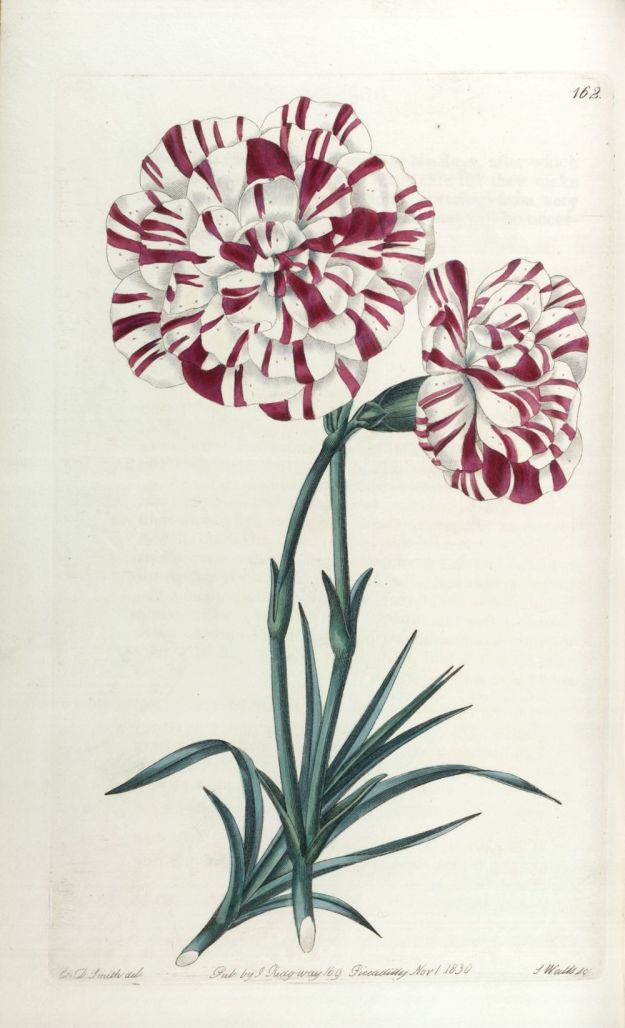

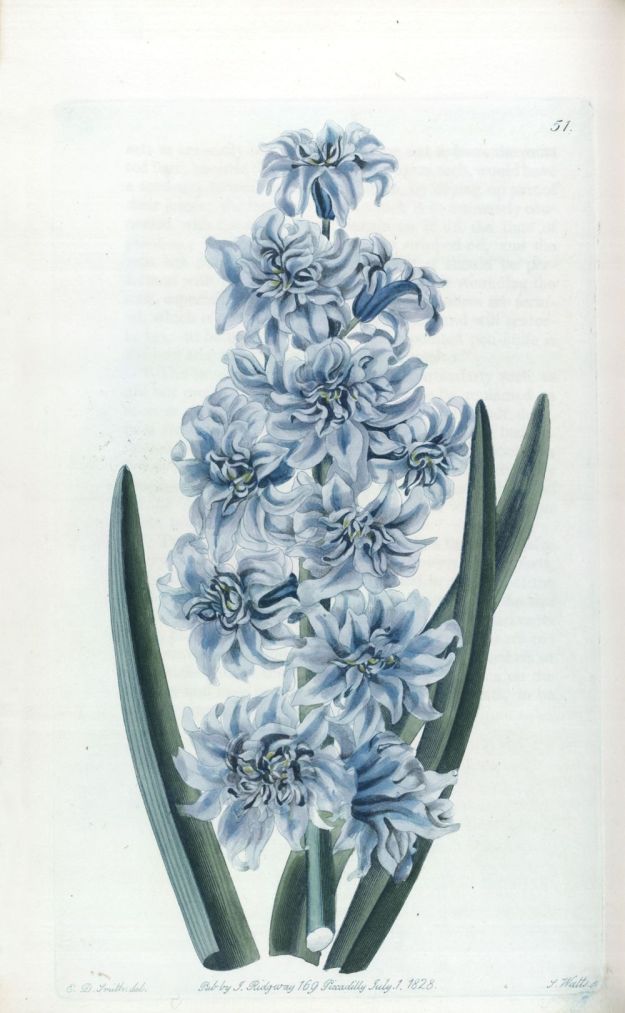

These coloured engravings from The Florist’s Guide, and Cultivator’s Directory Vols I and ll by Robert Sweet invite us into the world of the florist in the early 19th century.

At this time, the term ‘florist’ was given to those engaged in cultivating flowers for pleasure, or for show, rather than for the cut flower trade. The favoured blooms were carnations and pinks, ranunculus, tulips, hyacinths, polyanthus and auriculas – although Sweet’s Directory also includes dahlias (then called georginas) and roses. Double flowers were prized, as were the striped and flecked patterns of the tulips and carnations. Engravings by S Watts (after original paintings by Edwin Dalton Smith) allow us to understand what these choice plants must have looked like.

The plants and bulbs discussed in the Directory were for sale from a network of growers and Sweet’s use of high quality coloured images to promote them demonstrates his talent for horticultural marketing.

Albion Tulip from The Florist’s Guide, and Cultivator’s Directory Vol ll by Robert Sweet (1827 – 1832). Engraved by S. Watts after an original by Edwin Dalton Smith.

Hogg’s Queen Adelaide Dianthus from The Florist’s Guide, and Cultivator’s Directory Vol ll by Robert Sweet (1827 – 1832).

Engraved by S. Watts after an original by Edwin Dalton Smith.

‘Porcelaine Sceptre Hyacinth’, Hyacinthus orientalis var. sceptrifirmis, engraved by S. Watts after an original by Edwin Dalton Smith.

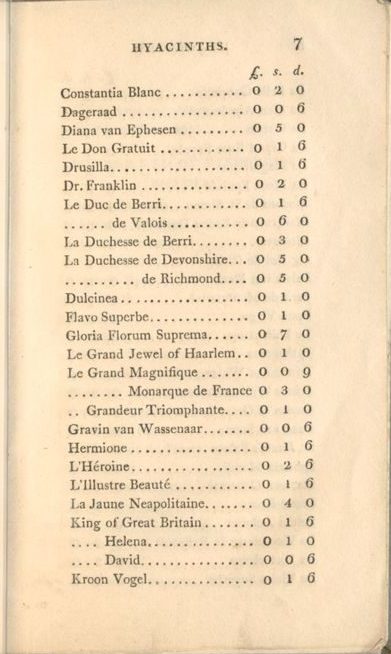

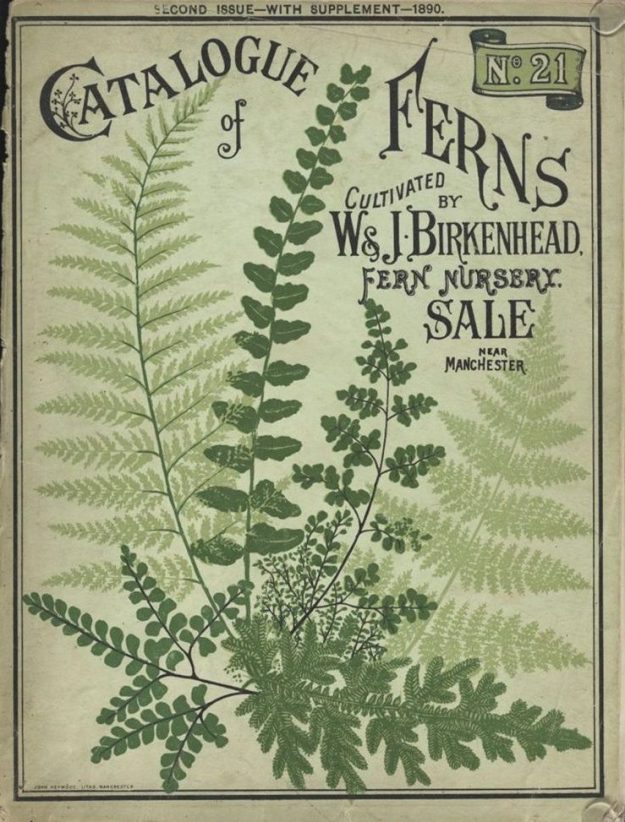

The popularity of florist’s flowers is echoed in the historic nursery catalogues dating from the mid to late 18th century that have been added to the Digital Collection, containing pages of auricula, hyacinth and tulip varieties. An 1890 catalogue listing over 1,400 fern varieties for sale from a company based near Manchester shows how horticultural tastes had changed by the late 19th century, when the craze for ferns had taken hold.

Fine double hyacinth and other curious flower roots, and seeds, imported chiefly from Holland, France, America, Italy, Botany Bay, &c. by John Mason, at the Orange Tree, 152, Fleet Street, London c. 1790

Catalogue of over 1.400 species and varieties of ferns and selaginellas cultivated by W. & J. Birkenhead, Fern Nursery, Sale; 17 and 19, Washway Road, Sale; and Park Road Nursery, Ashton-on-Mersey, near Manchester. Our principal nursery is five minutes’ walk and our Park Road Nursery eight minutes’ walk from Sale Station, on the Manchester, South Junction, and Altrincham Railway, five minutes from Manchester. First-class Queen’s Jubilee Gold Medal, 1887

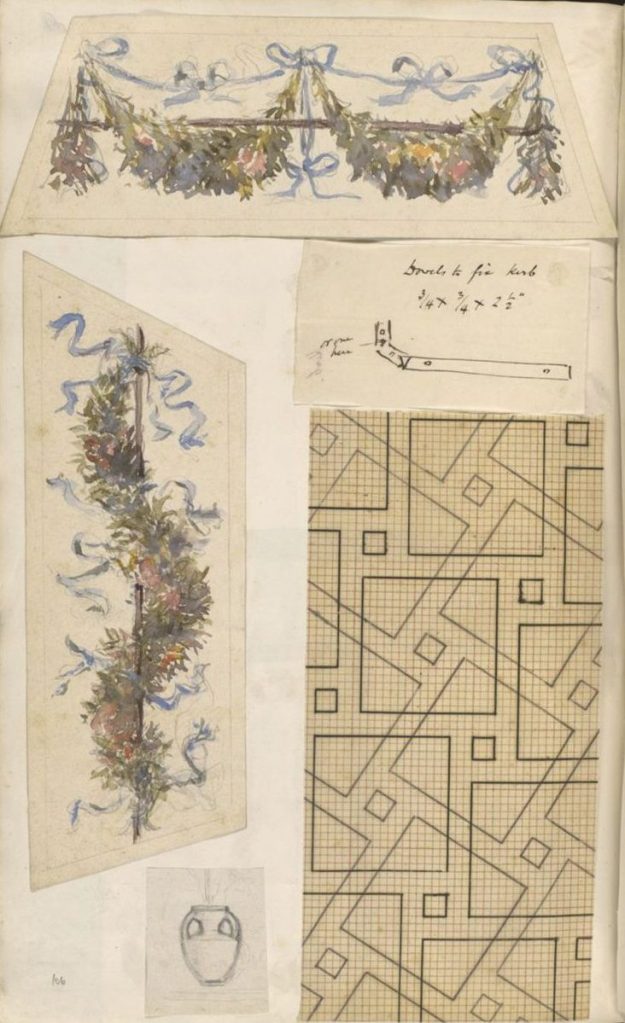

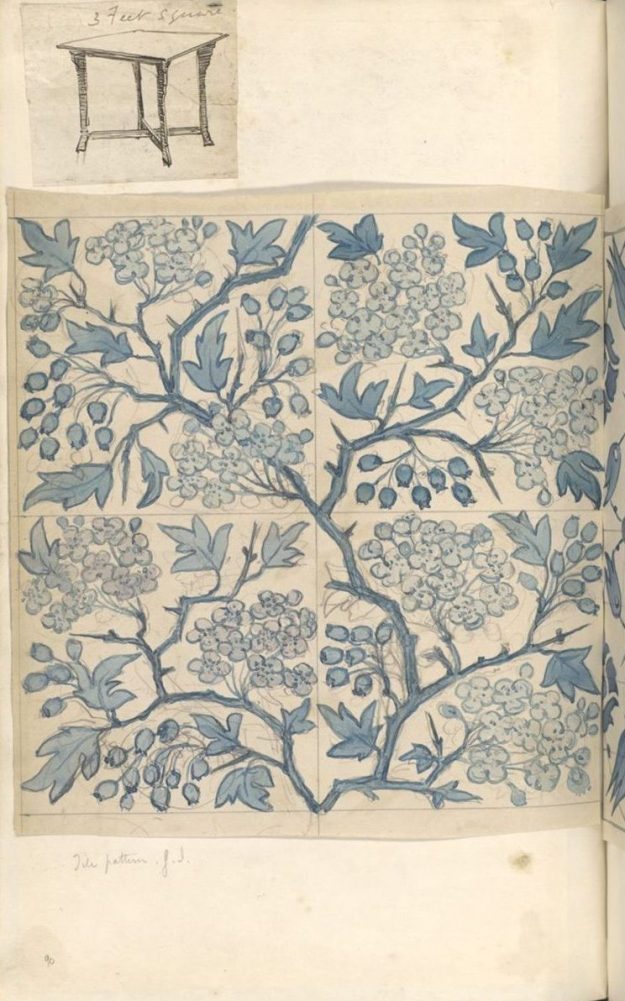

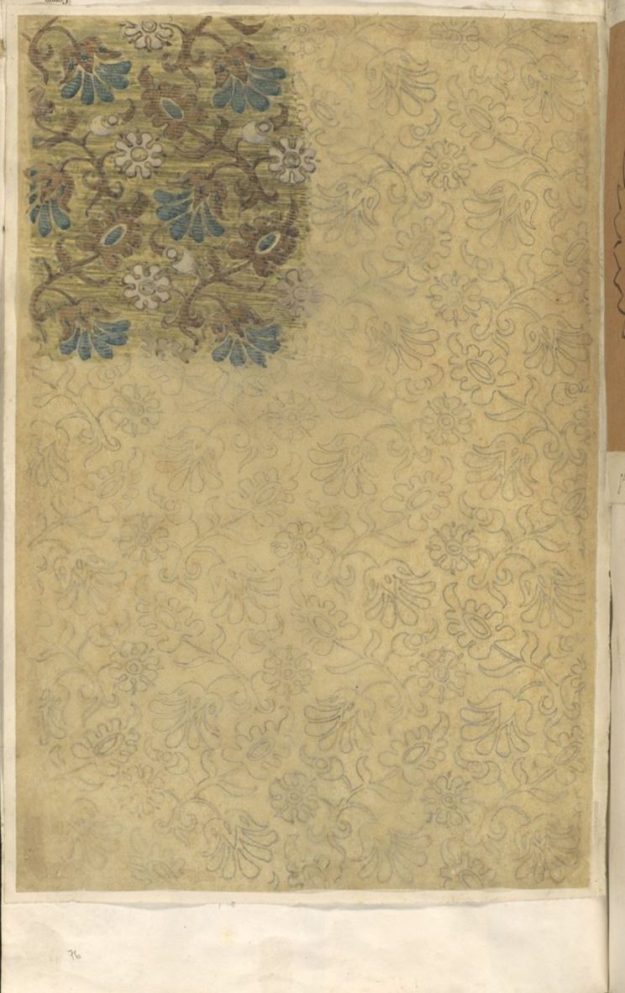

A sketchbook belonging to Gertrude Jekyll (1843 – 1932) is one highlight of the archive section. Influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, Jekyll studied painting, embroidery, gilding, carving and photography, before focusing her attention on a career in landscape and garden design.

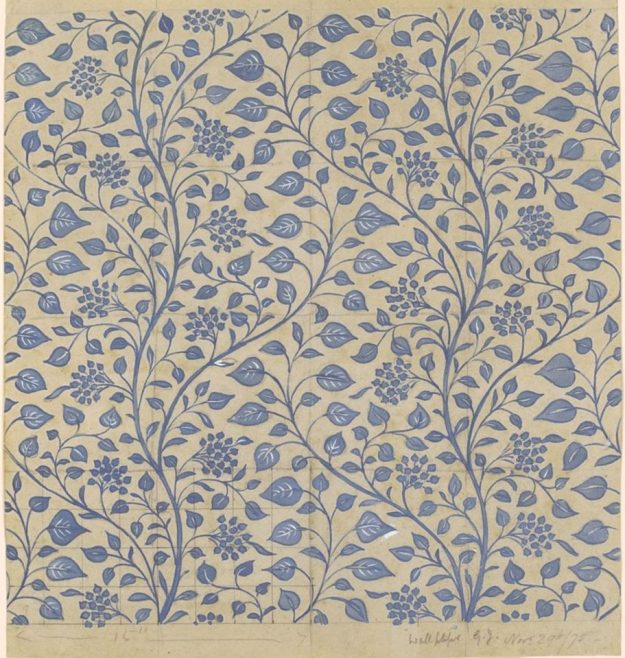

These wide ranging interests are evident in her sketchbook, containing a profusion of Jekyll’s sketches of flowers, leaves, architectural details, designs for jewellery, fragments of geometric pattern, swags, and places of cultural interest. These have been individually cut out and assembled into a scrapbook of visual references. Some projects must have taken considerable time to complete – four separate tile designs using studies of hawthorn combine cleverly to form a larger repeat pattern, and there are intricate designs for floral wallpaper.

Insights provided by the sketchbook demonstrate how Jekyll’s interest in decorative arts enriched her planting designs.

Floral swags, geometric design and a jug

Gertrude Jekyll

Floral patterns, architectural details and lettering

Gertrude Jekyll

Tile Pattern by Gertrude Jekyll

Floral Wallpaper pattern

Wallpaper, Blue Vine Design

Gertrude Jekyll

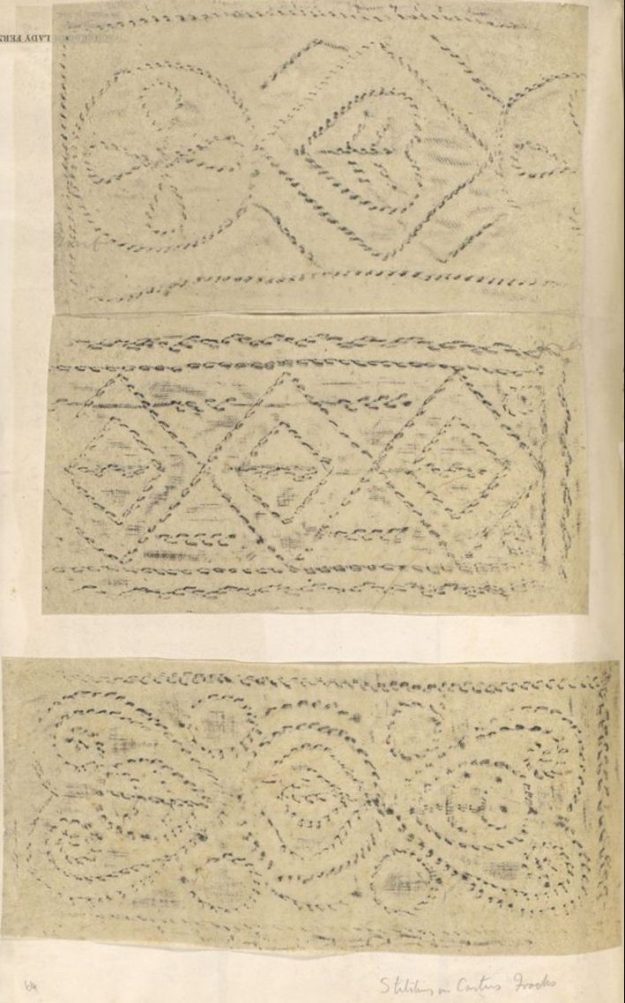

Jekyll’s interest in vernacular design is also clear, in her records of stitching designs from smocks worn by agricultural workers. Jekyll has made these impressions by using pencil and paper, in the manner of a brass rubbing. Her book Old West Surrey (1904) features houses, furniture, tools and clothes used by working people in the late 19th century, including smocks like these.

Stitching on Country Smocks

Gertrude Jekyll

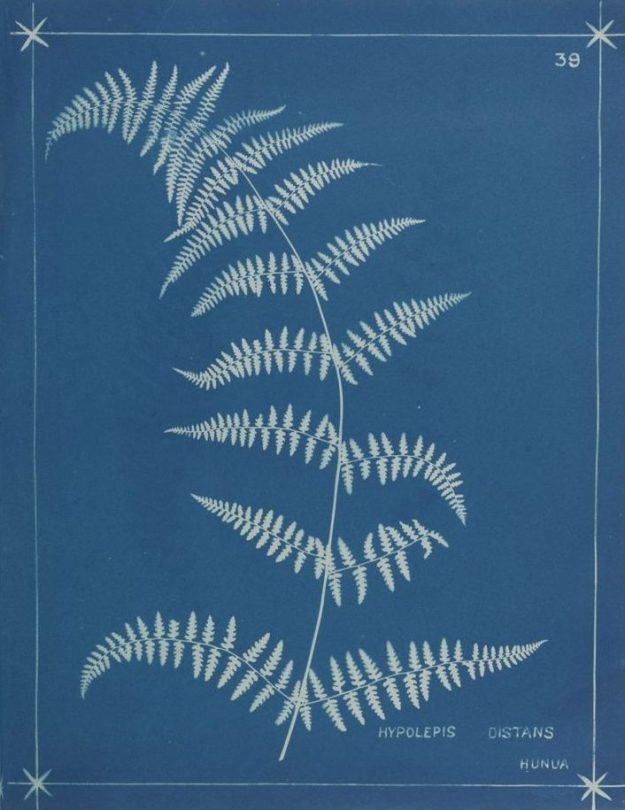

The photography section records the history of the RHS as an organisation, with images showing the construction of RHS Kensington Gardens in the 1860s and the development of the gardens at RHS Wisley in the 1930s. The delicate beauty of fern species in New Zealand is captured in a series of cyanotypes by Herbert B Dobbie, published in 1880, and a series of autochromes by William Van Sommer provide glimpses of English gardens from the early 20th century .

Cyanotype of Hypolepis distans, from the book ‘New Zealand Ferns’ Herbert B Dobbie, 1880

Autochrome of calceolarias, Barton Nurseries, by William Van Sommer 1913

Although it could be said that the RHS is rather late to the digitisation party – most major museums and libraries started to share their content online more than a decade ago – now that it has arrived, the RHS Digital Collection is undeniably full of wonder. I hope you’ll be persuaded to explore, and discover your own treasures. Link below:

Further reading:

RHS Digital Collections here