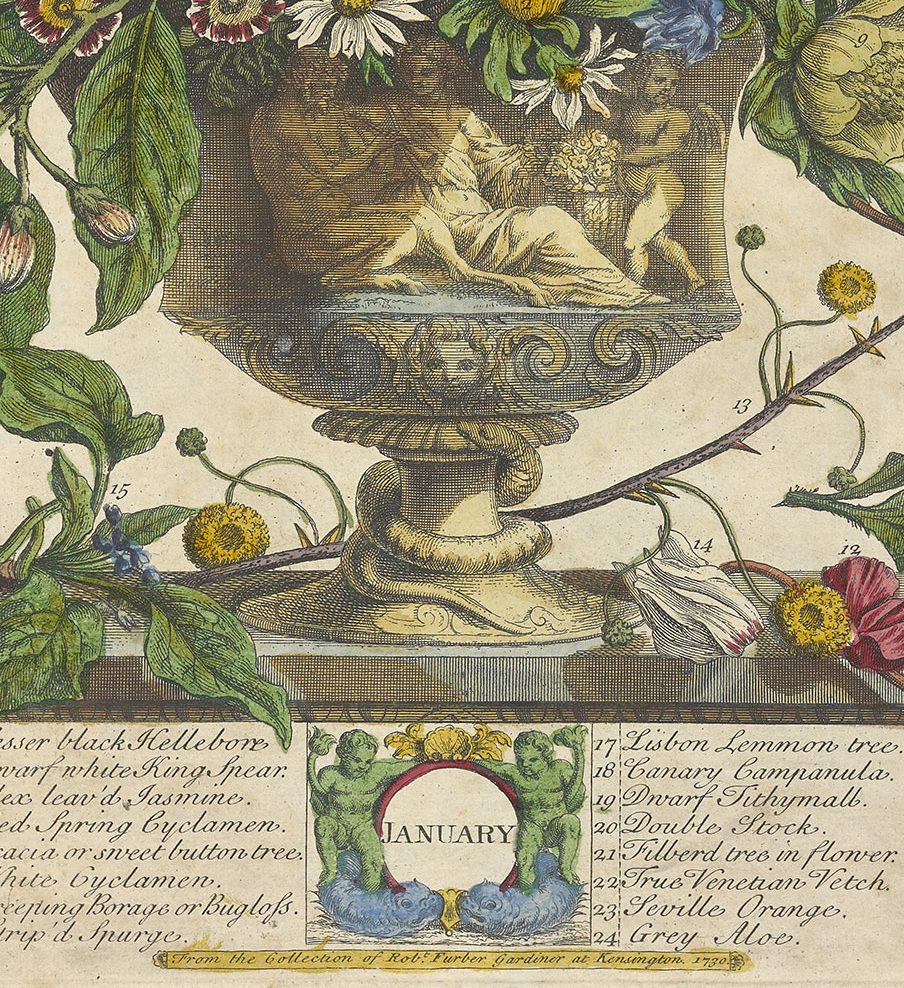

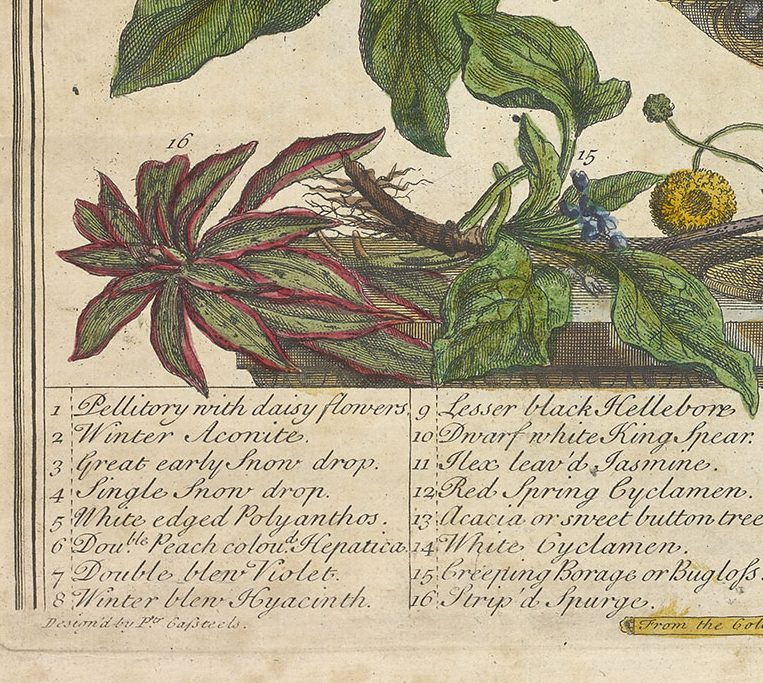

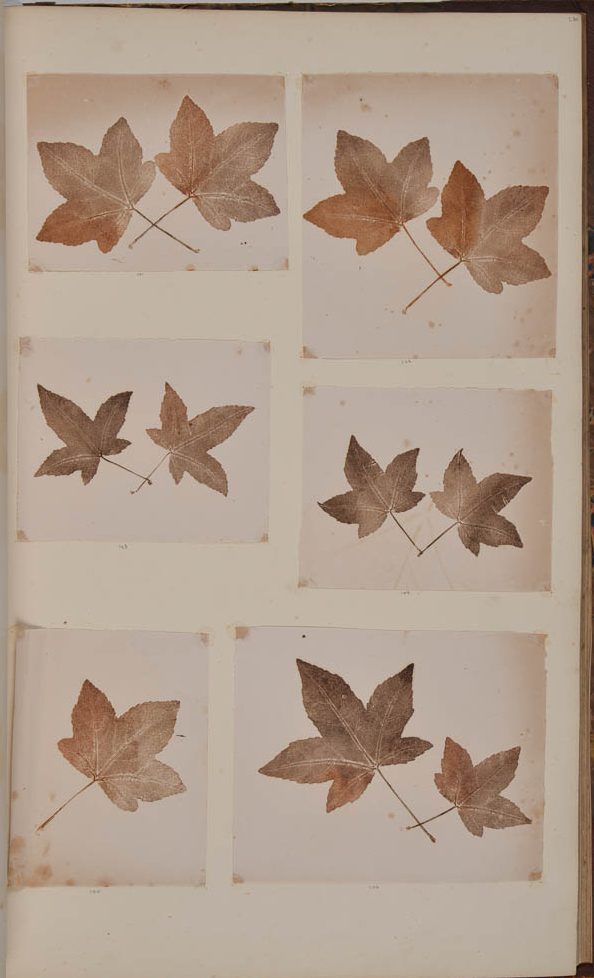

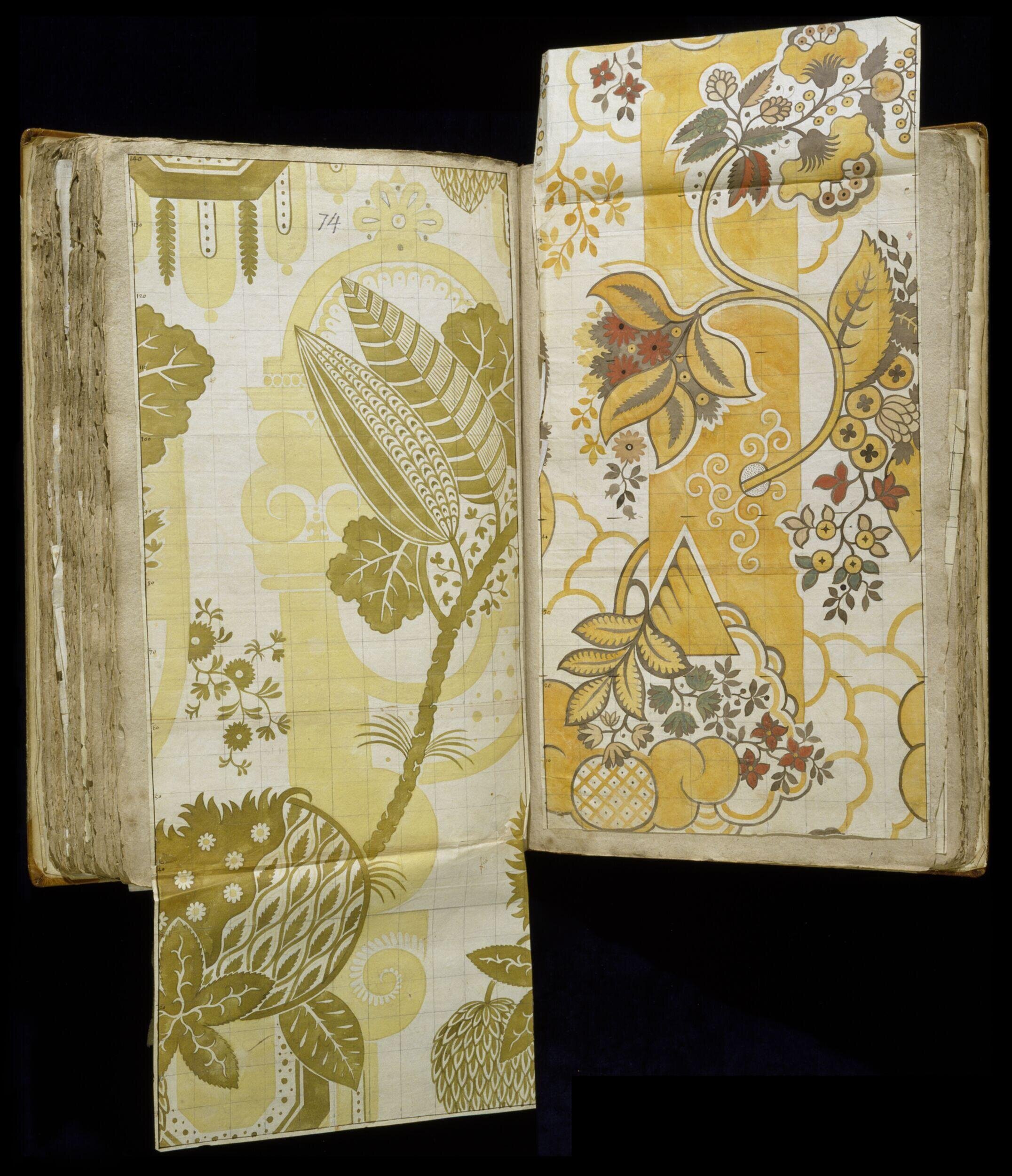

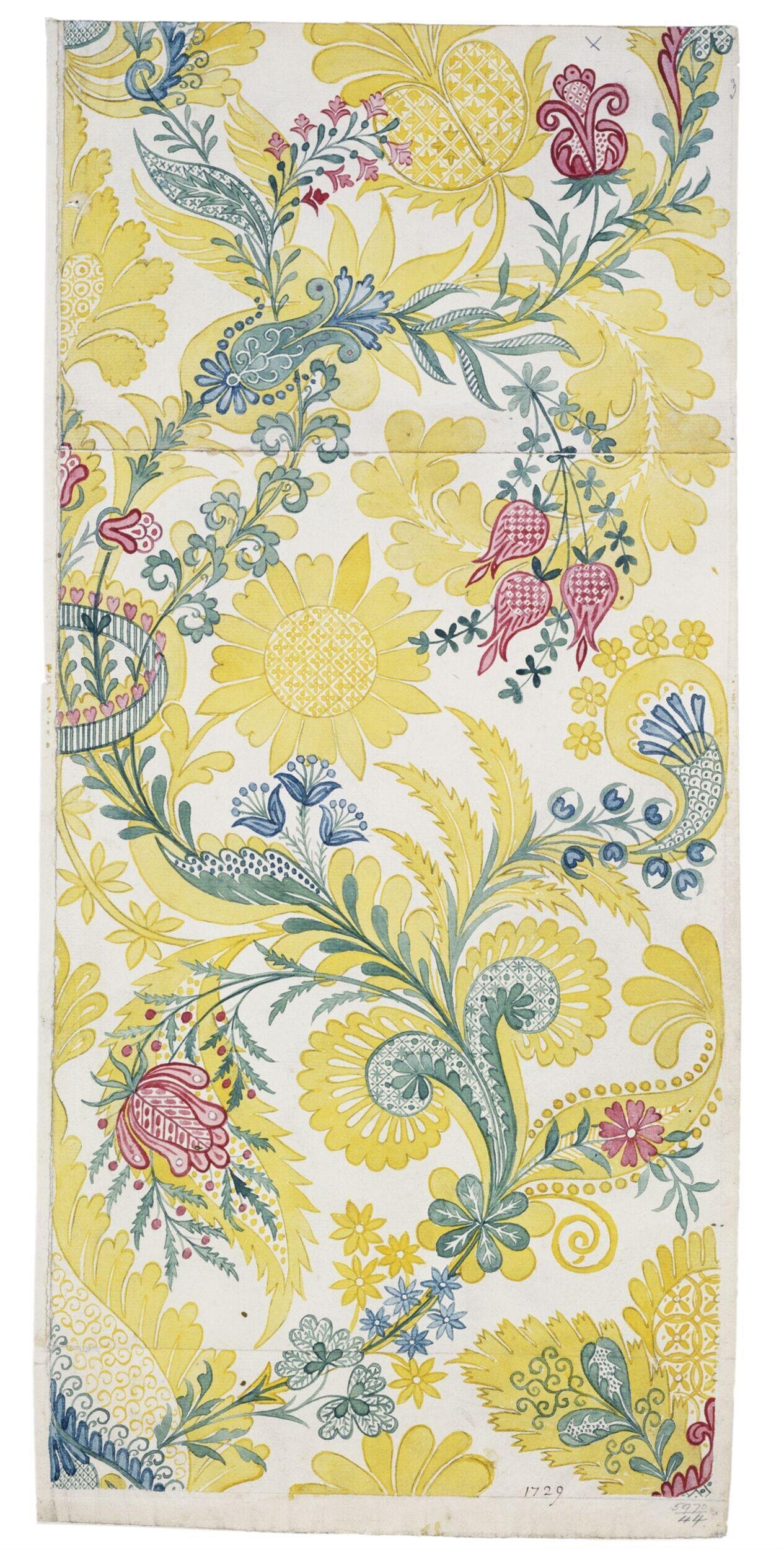

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726 – 1728 All images from the V&A online Colllections

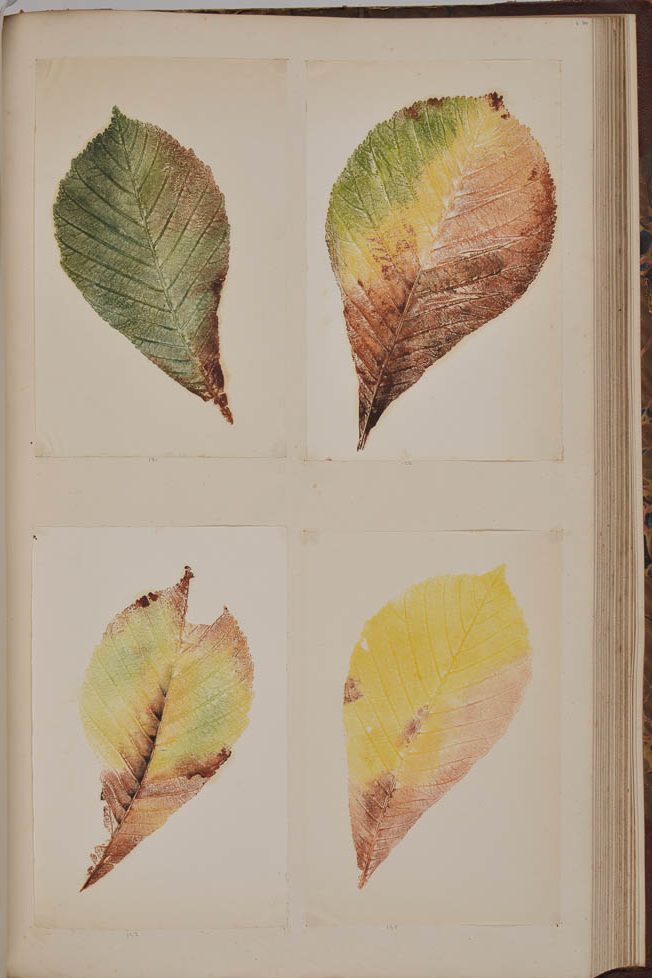

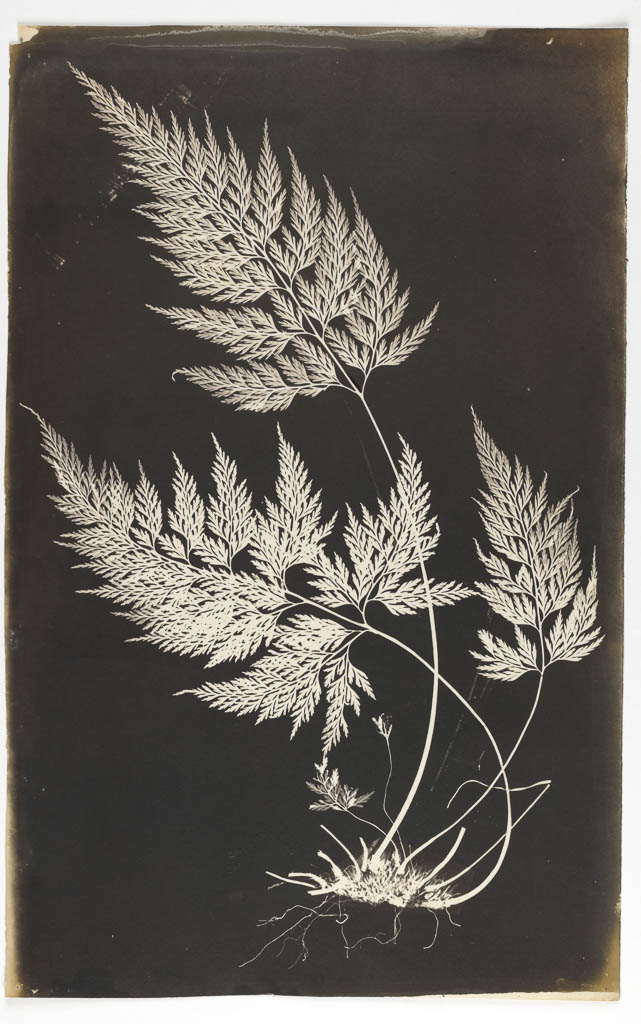

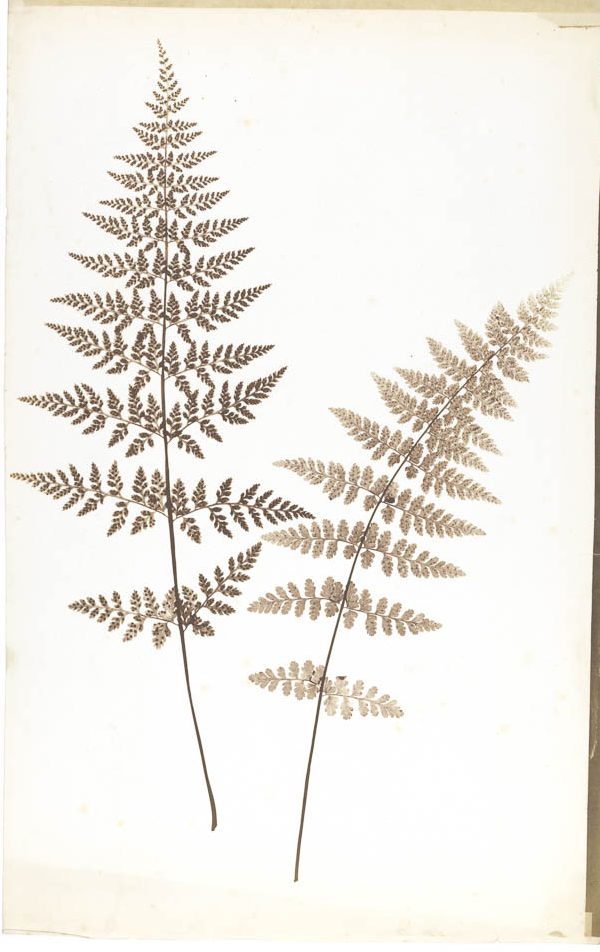

Housed at the Victoria & Albert Museum is a remarkable collection of Anna Maria Garthwaite’s designs for woven silks. Her colourful pattern books of watercolour designs produced from the mid-1720s to the 1750s reveal an astonishing range of fashionable styles inspired by flowers, foliage and organic forms.

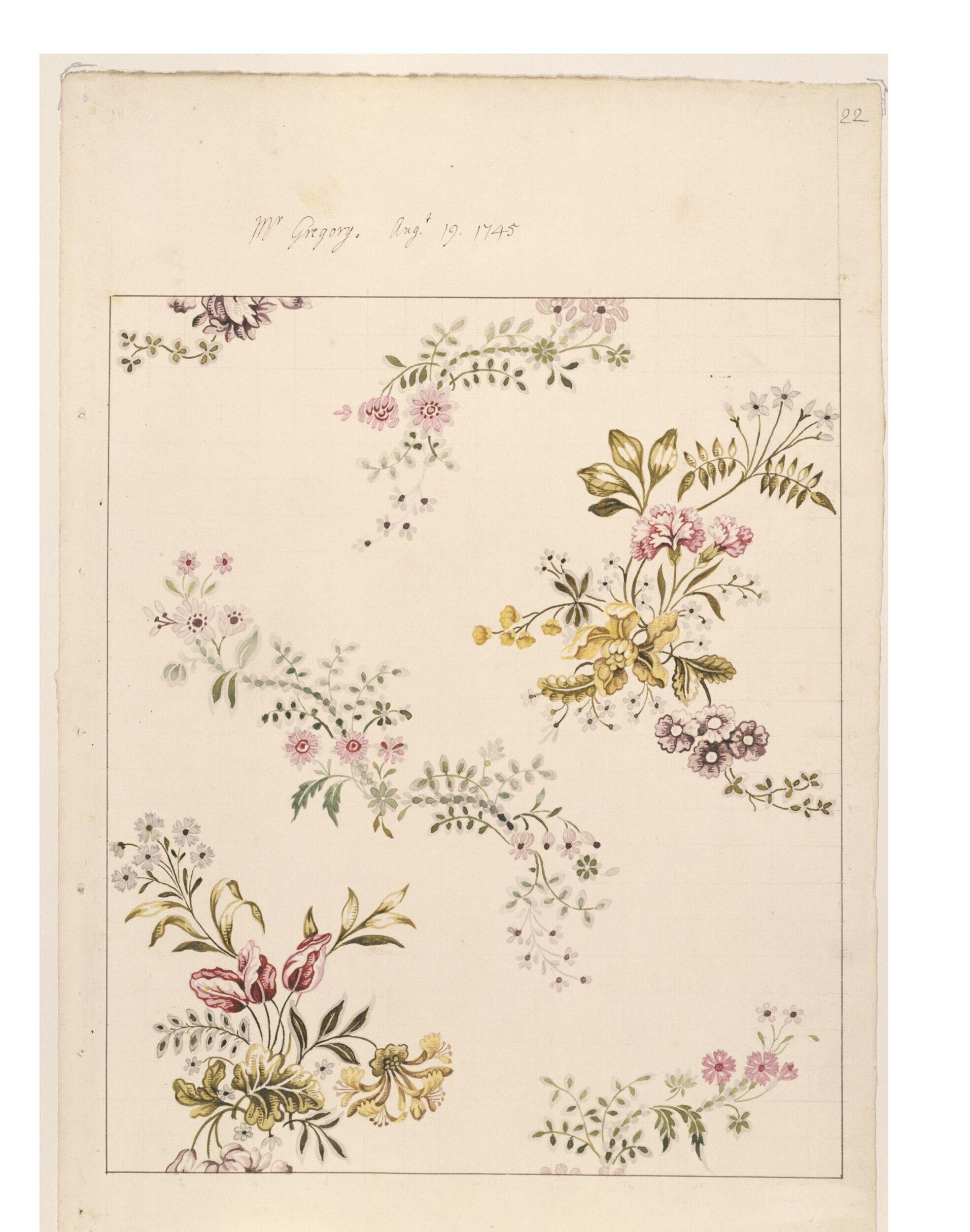

Exactly how Garthwaite developed her artistic skills and learned the craft of making complicated repeat patterns for fabrics is unknown, but she produced around a thousand fabric designs from the 1720s to 1750s, many of which she sold to silk weavers in Spitalfields, London. Each design was meticulously dated and often recorded the names of the weavers her patterns were sold to. Rare examples of the woven silks she designed still survive, both as whole garments, and fragments of cloth. Some of these are preserved at the Victoria & Albert Museum, and in textile collections across the world.

Anna Maria Garthwaite (1688 – 1763) was born in Harston, Leicestershire, the daughter of the Reverend Ephraim Garthwaite. She lived together with her twice widowed sister Mary in York from 1726 until 1728, when they relocated to Spitalfields, London, the heart of England’s silk weaving industry.

The house they purchased in Princelet Street (formerly Princes Street) was then part of a new development by Charles Wood and Simon Michell which began construction in the early 1700s on the site of a previous market garden. The house still stands today on the corner with Wilkes Street.

Silk weaving was already well established in Spitalfields by the 1600s and after 1685 English weavers were joined by protestant Huguenots weavers escaping religious persecution in France. Garthwaite’s records show she sold designs to both English and French weavers.

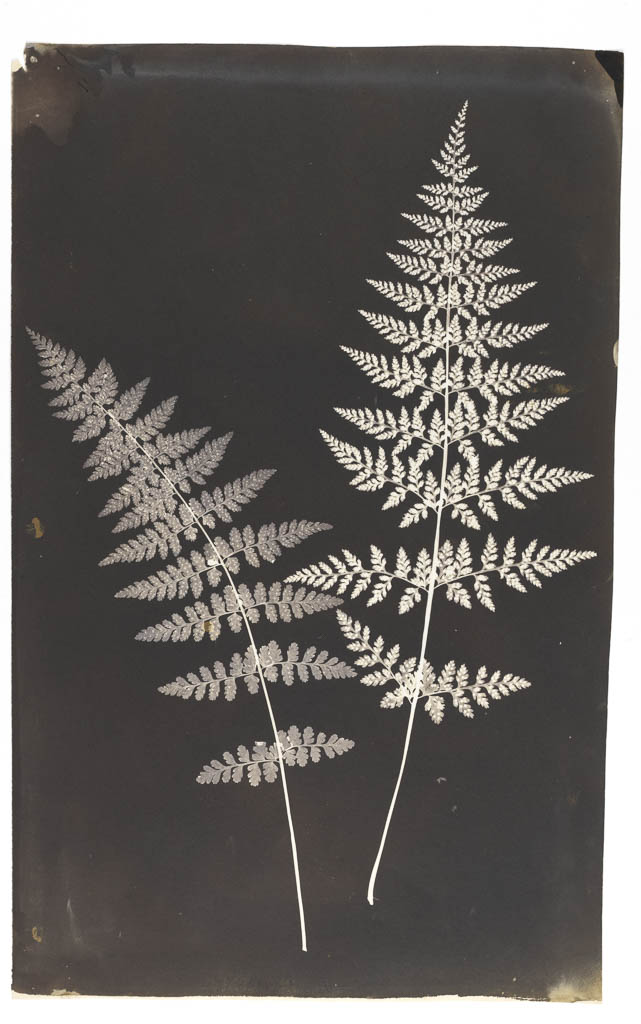

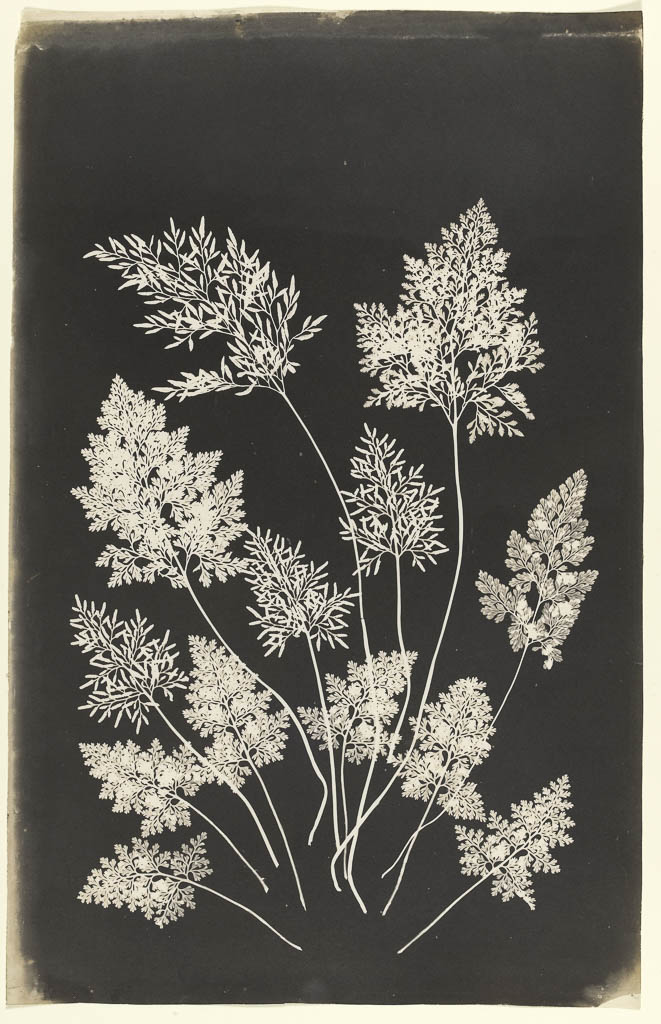

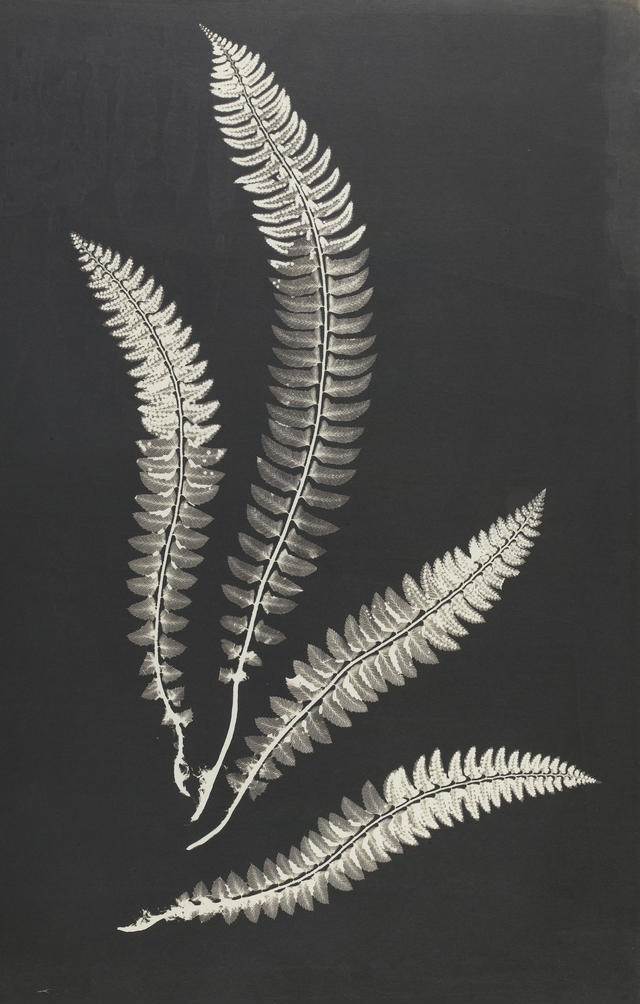

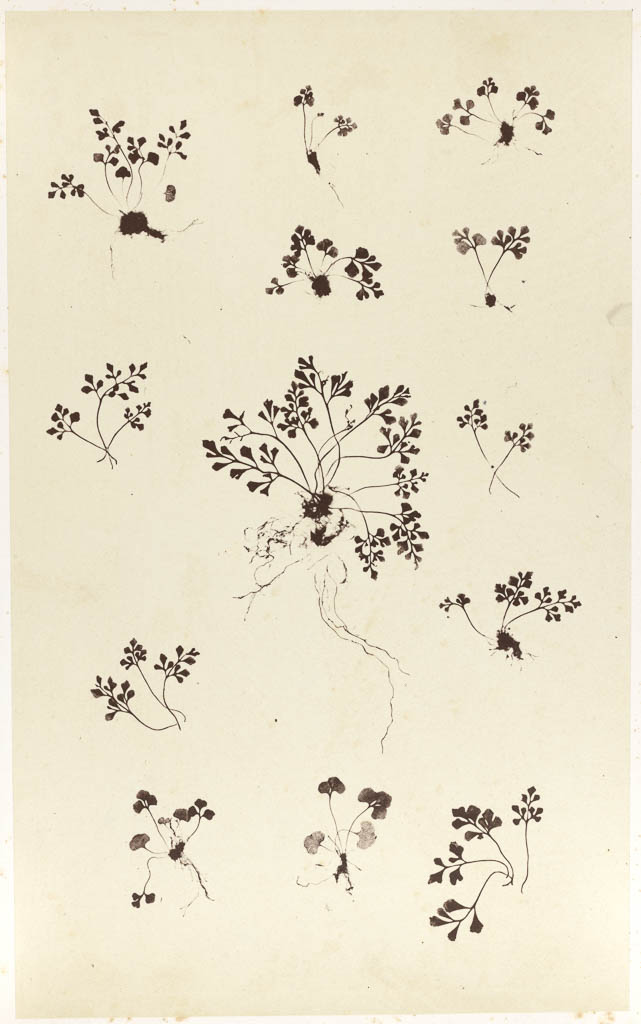

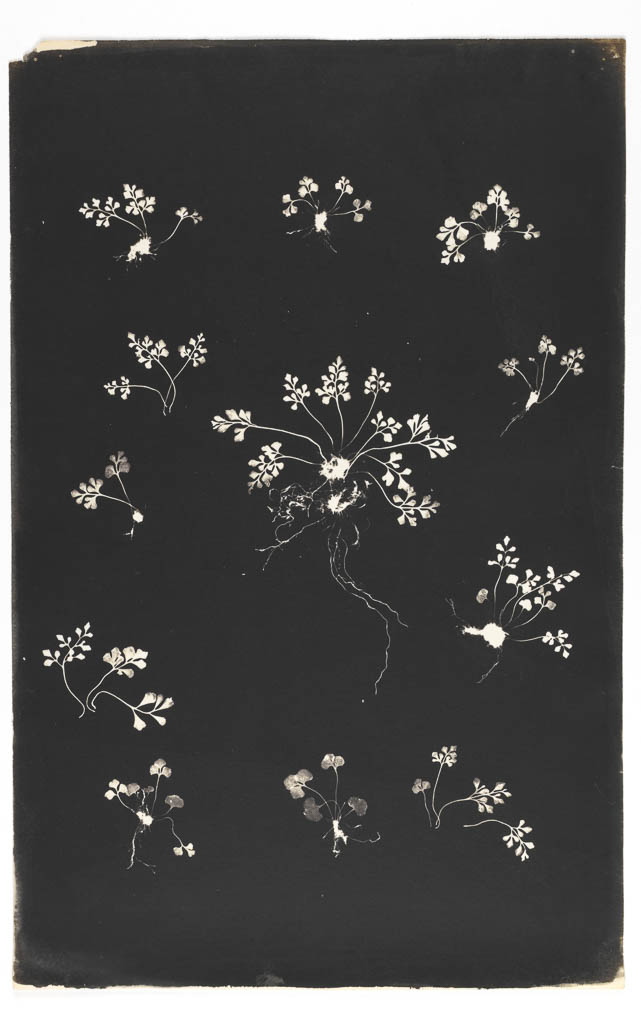

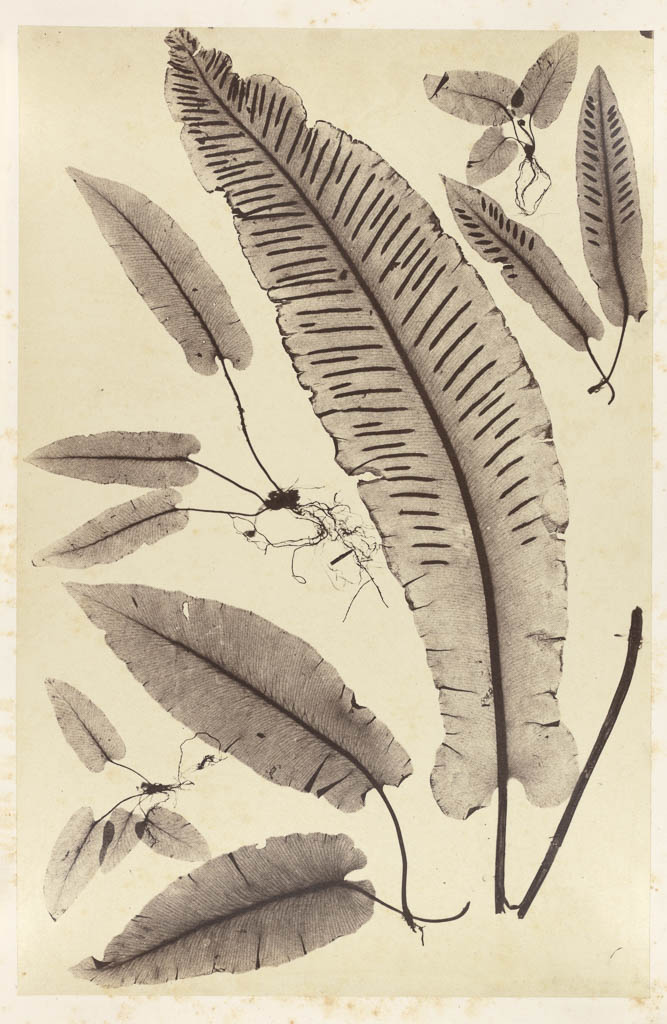

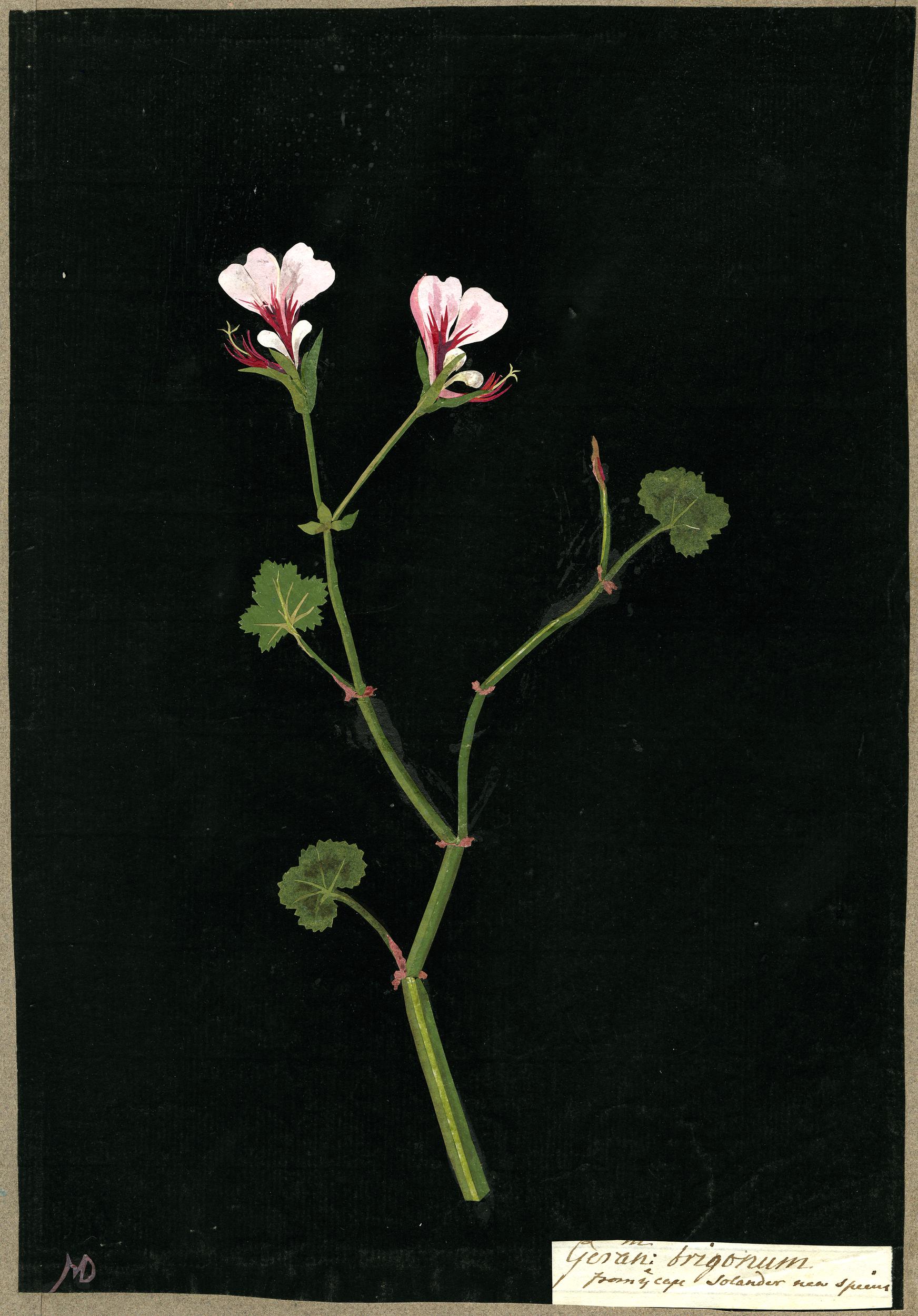

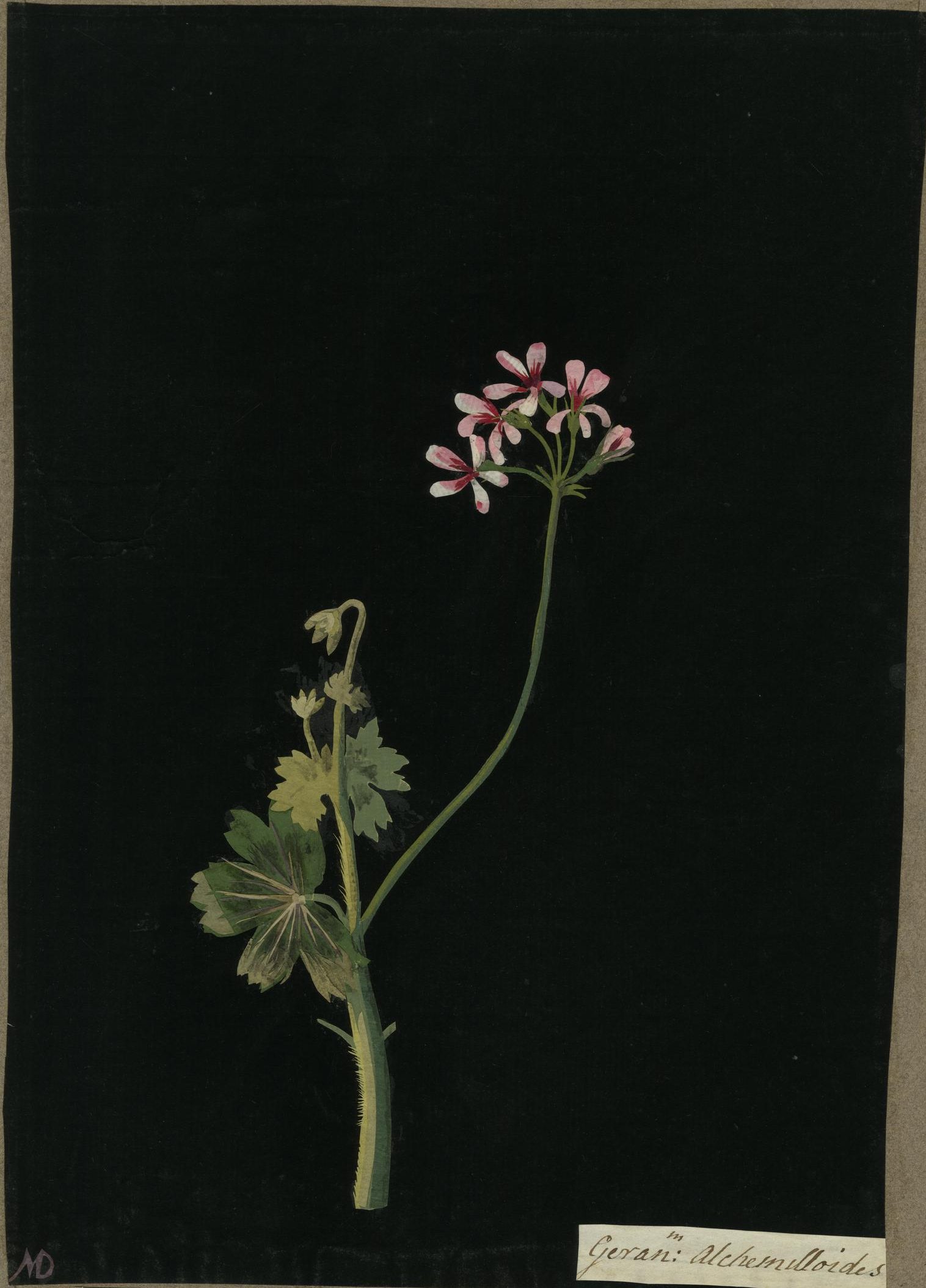

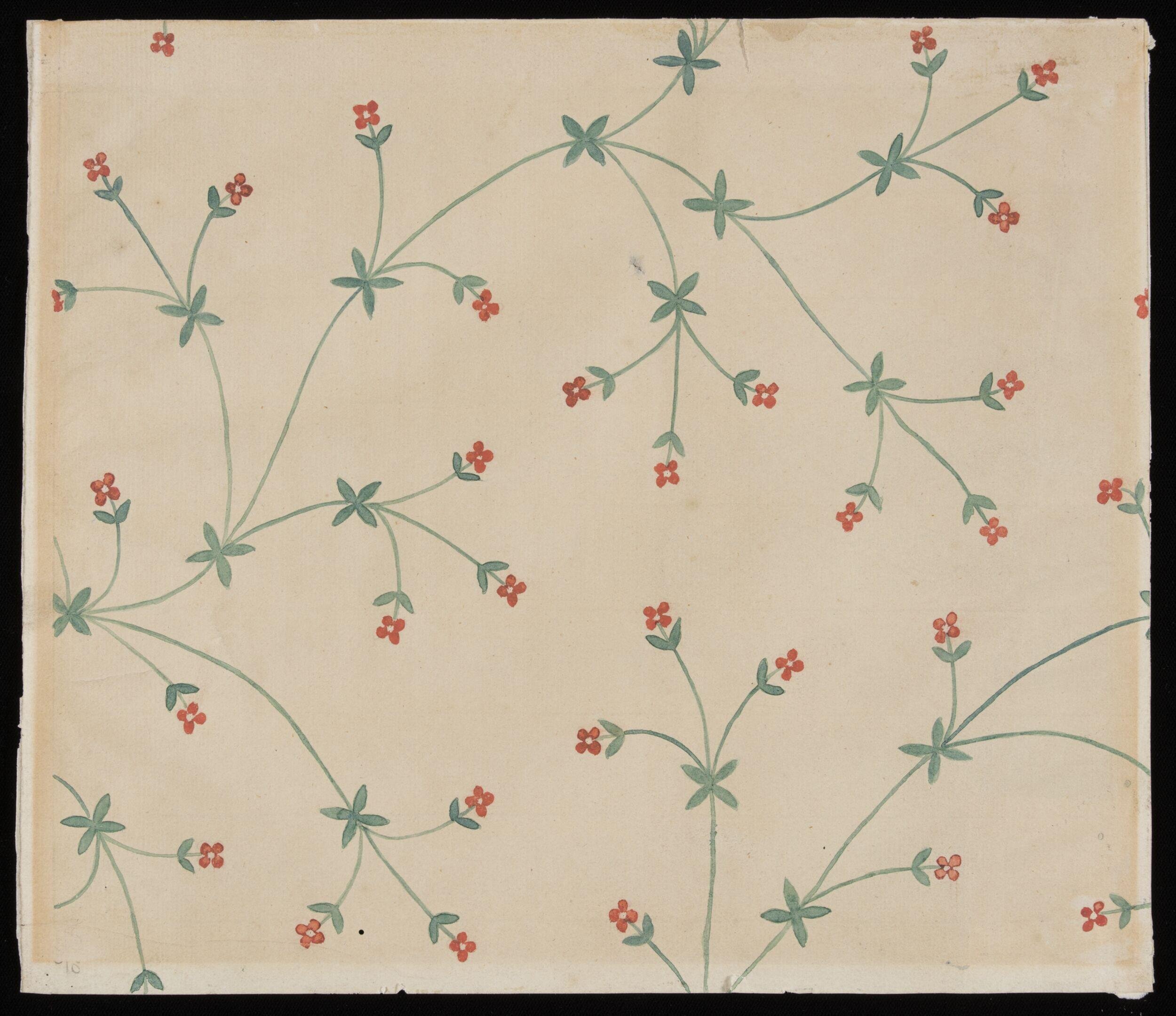

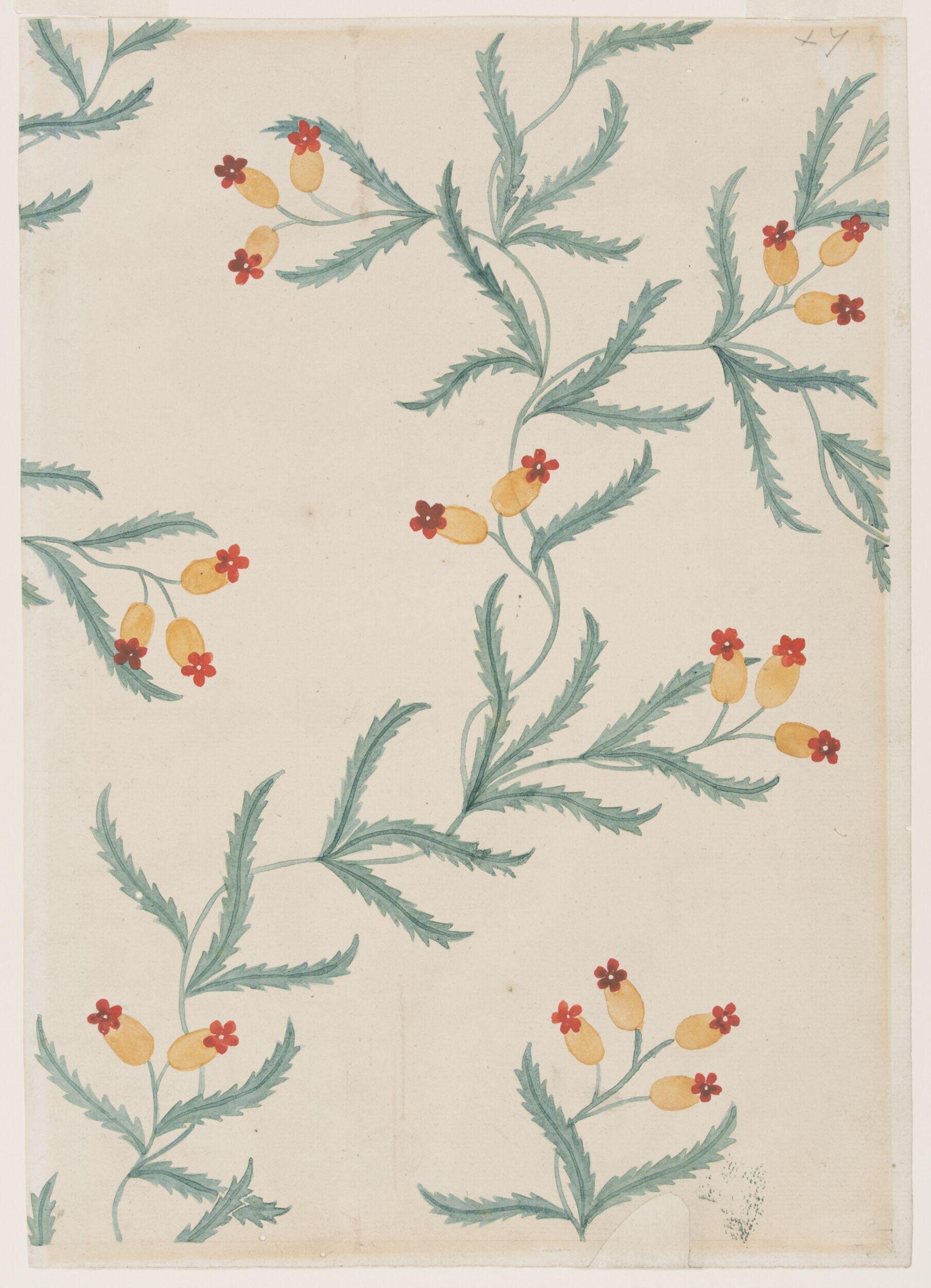

From Garthwaite’s pattern collection we can trace developments in her career as a designer. Garthwaite gave the title ‘before I came to London’ to a series of varied designs from the 1720s. One recurring theme from this period uses stylised studies of individual plant species and the intricate twining of their stems to create a repeat pattern. These tiny, red star shaped flowers (below) look like the common wildflower, scarlet pimpernel, (although this plant has five petals, rather than the four in Garthwaite’s design).

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726 – 1728

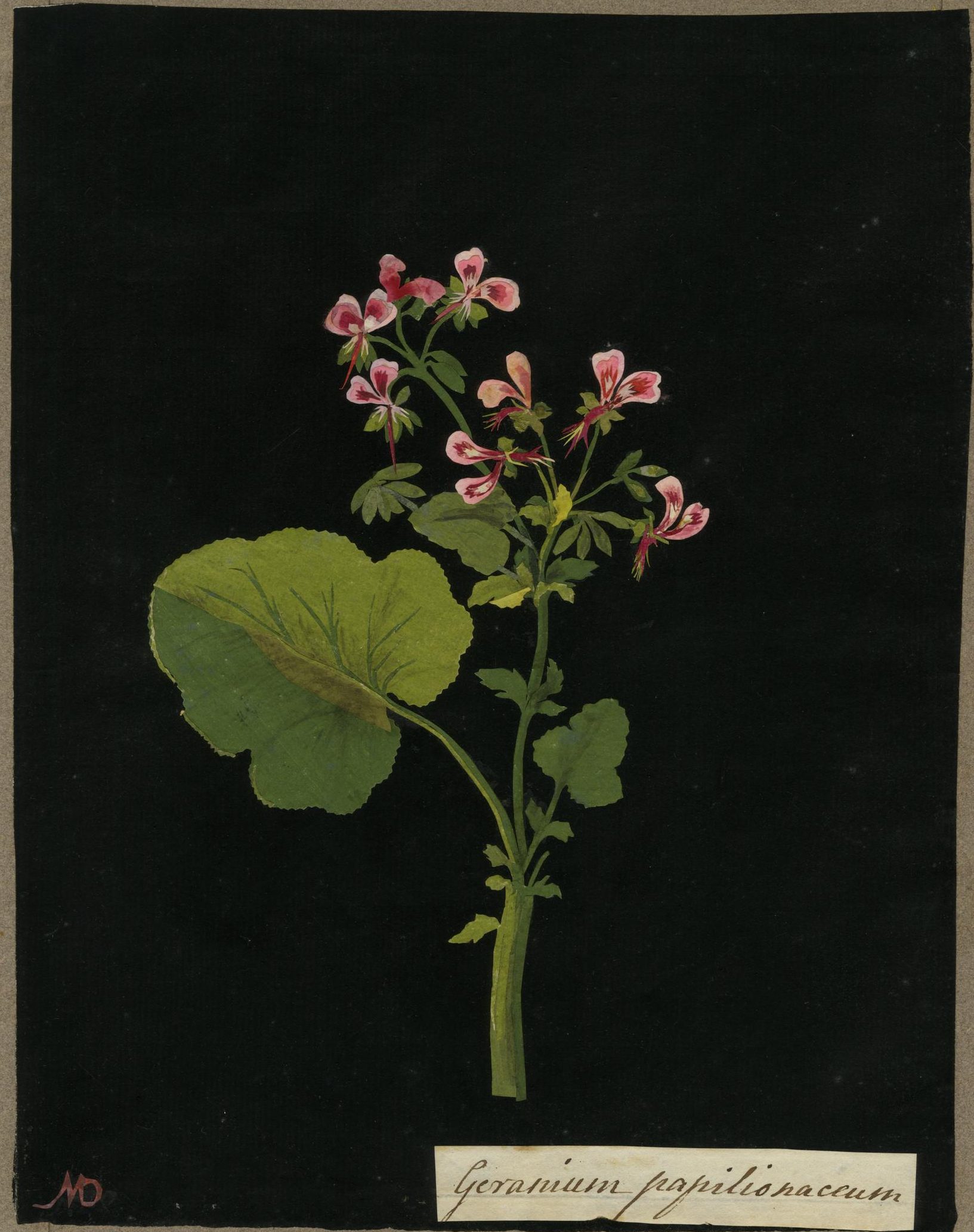

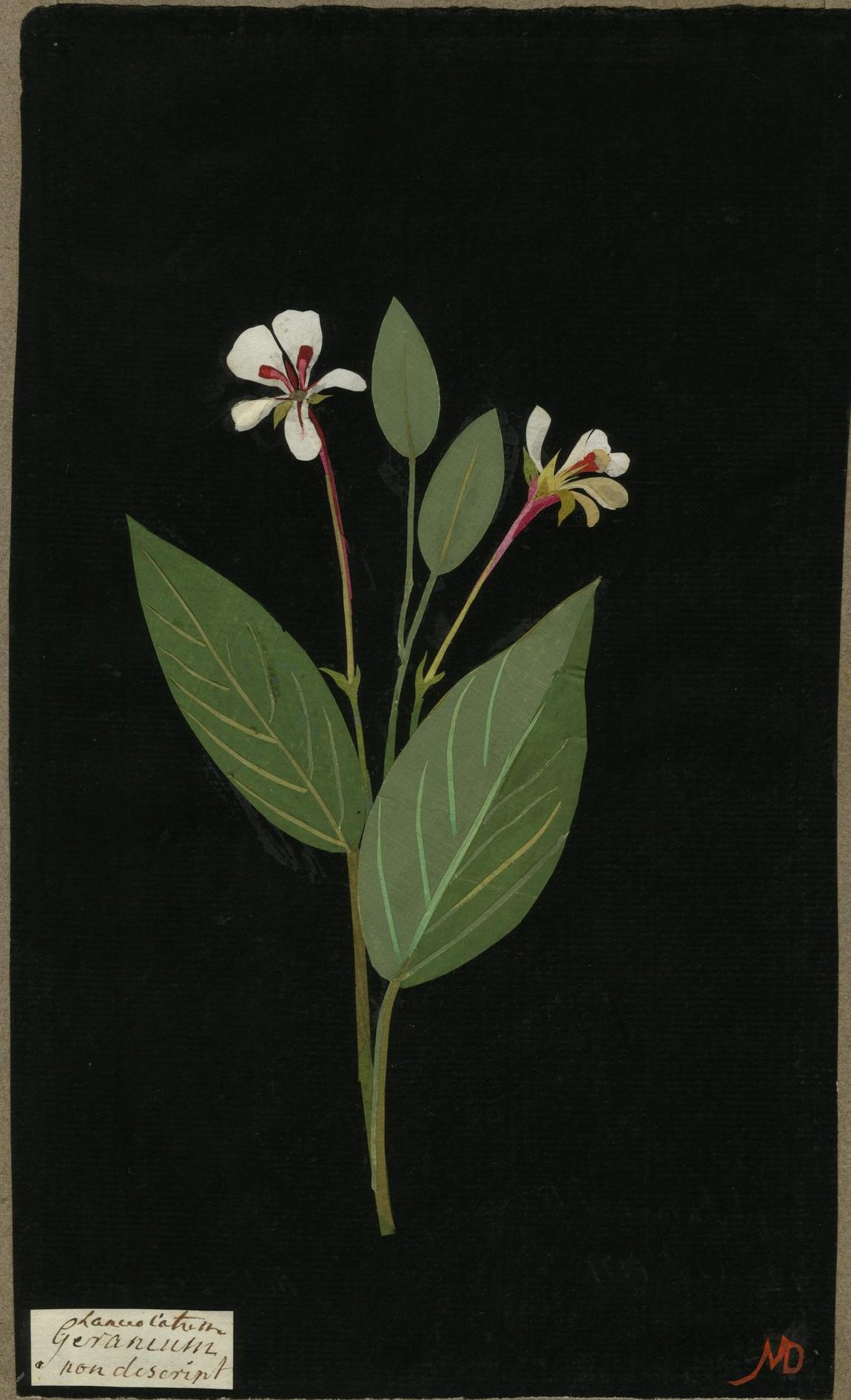

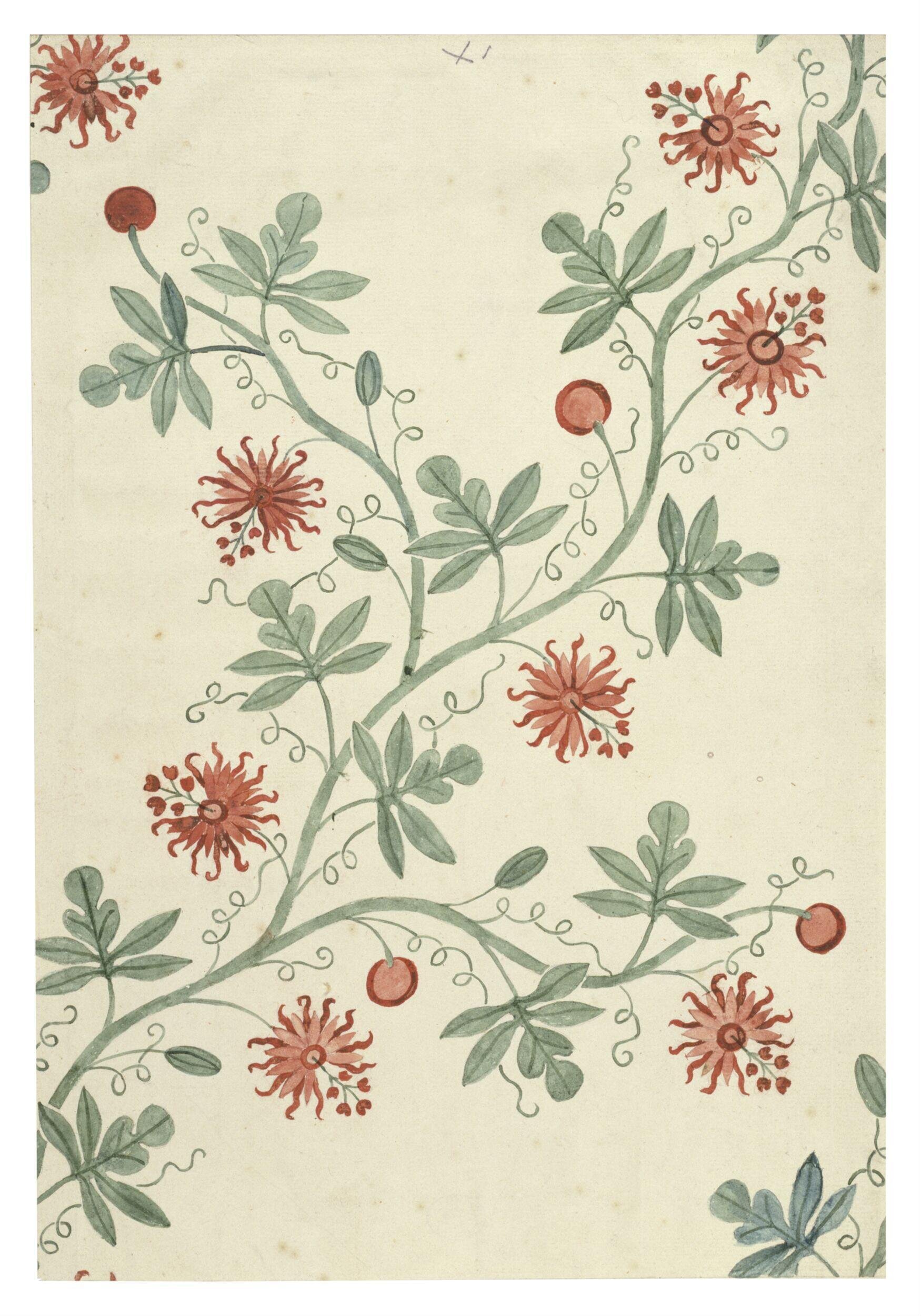

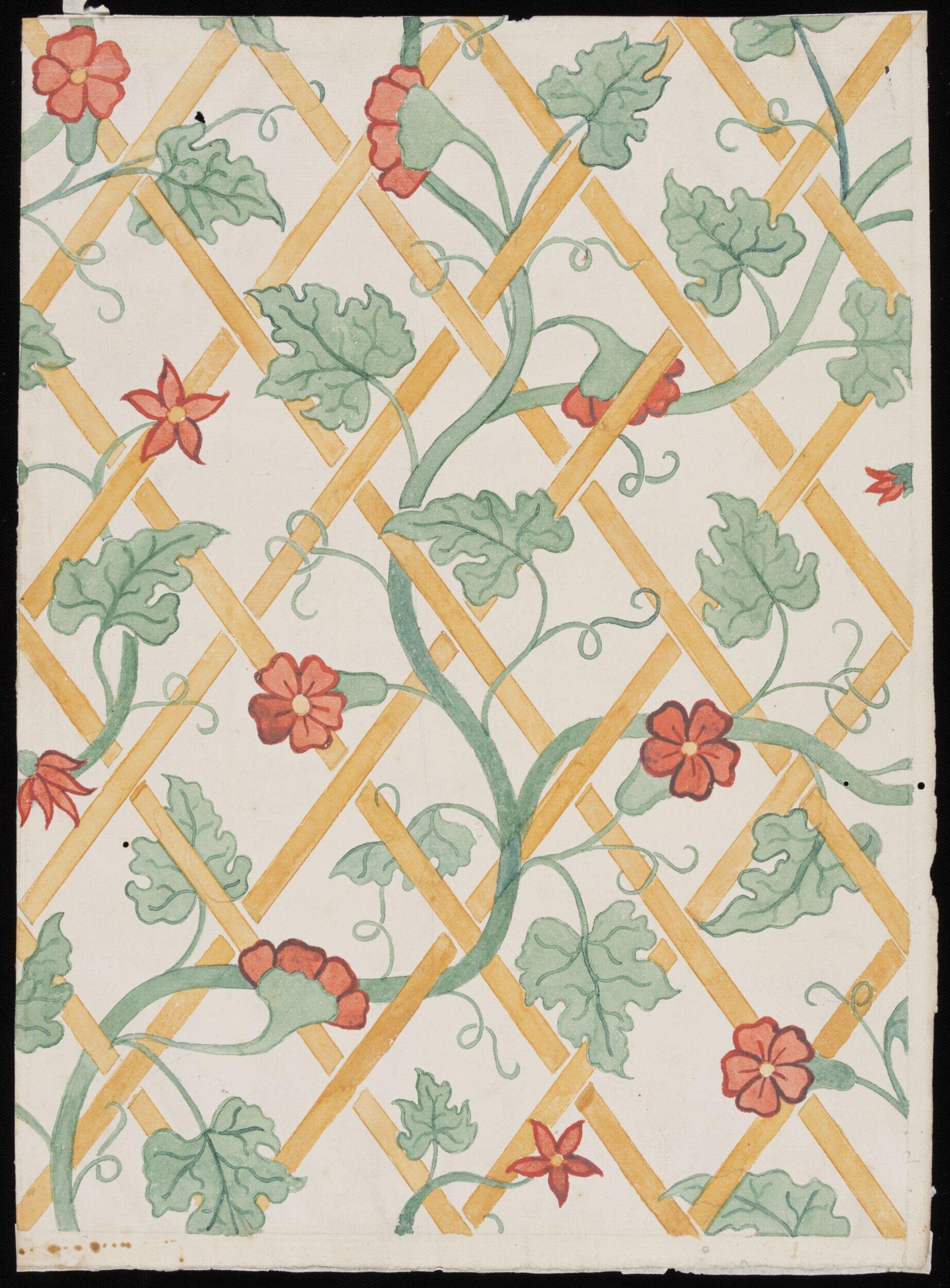

Other plants appear more exotic, like a red passion flower (below), and the red and gold tubular shaped flowers with finely cut leaves could possibly be a South African erica, or heath, popular with English plant collectors in the eighteenth century.

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca.1726

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726 – 1727

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726-1727

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726 – 1728

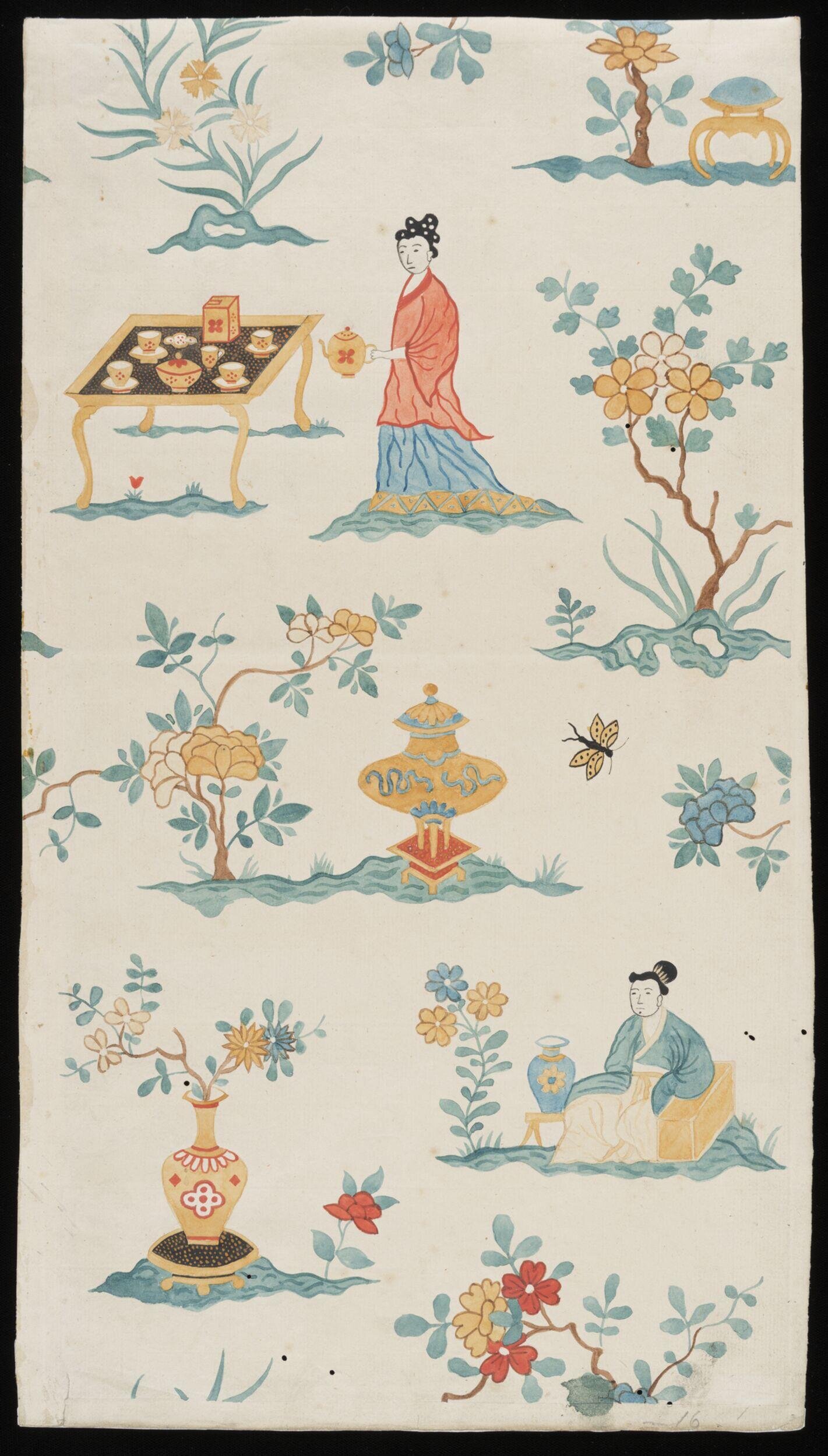

A nod here to the 18th century enthusiasm for Chinoiserie.

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726 – 1728.

The containers in this design (above) appear to be flower bricks, which had a series of small holes in the top enabling individual stems to be held upright and separate from each other.

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726-1728.

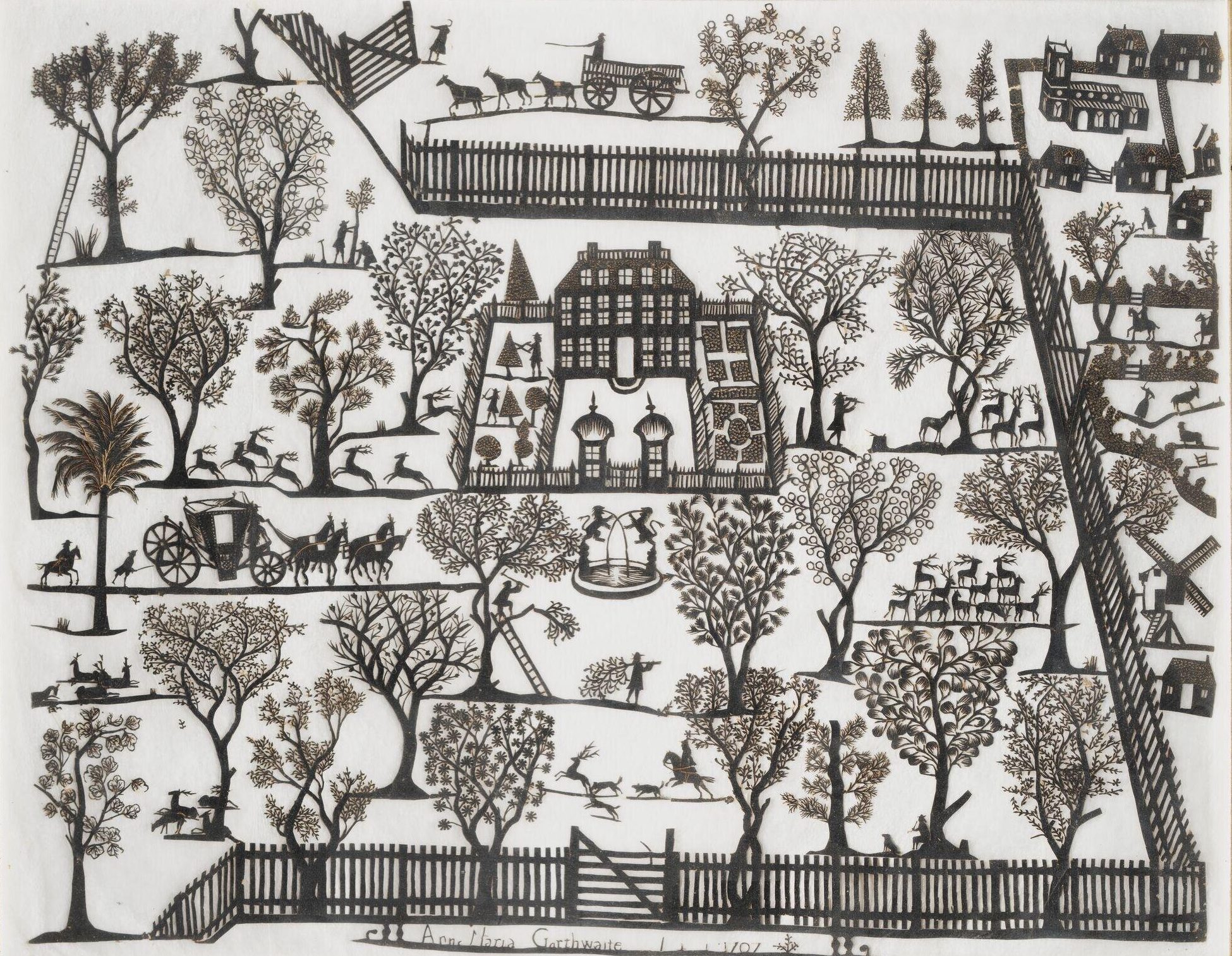

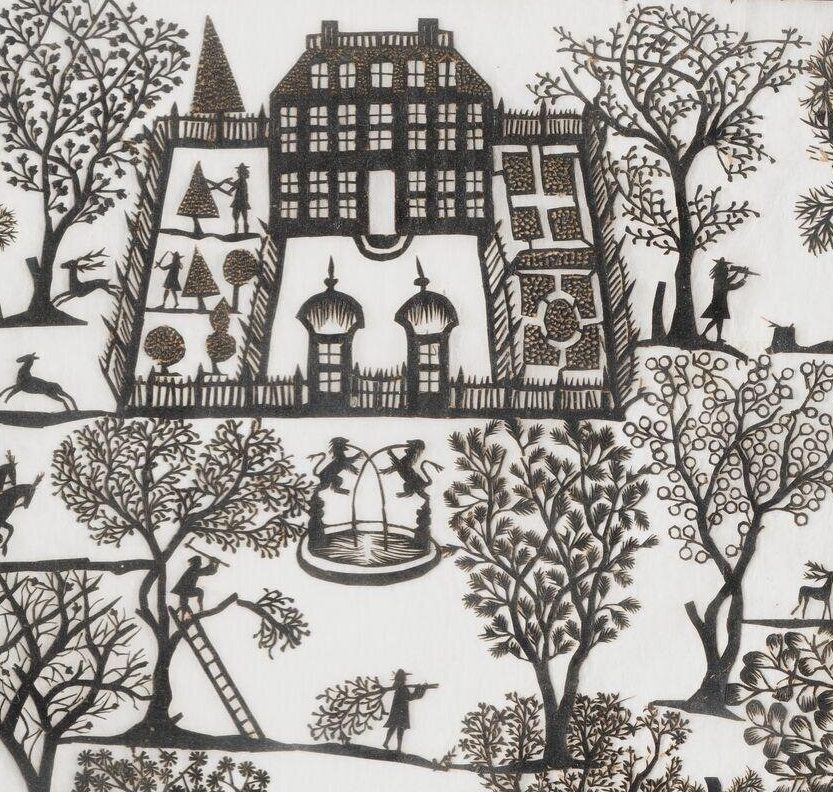

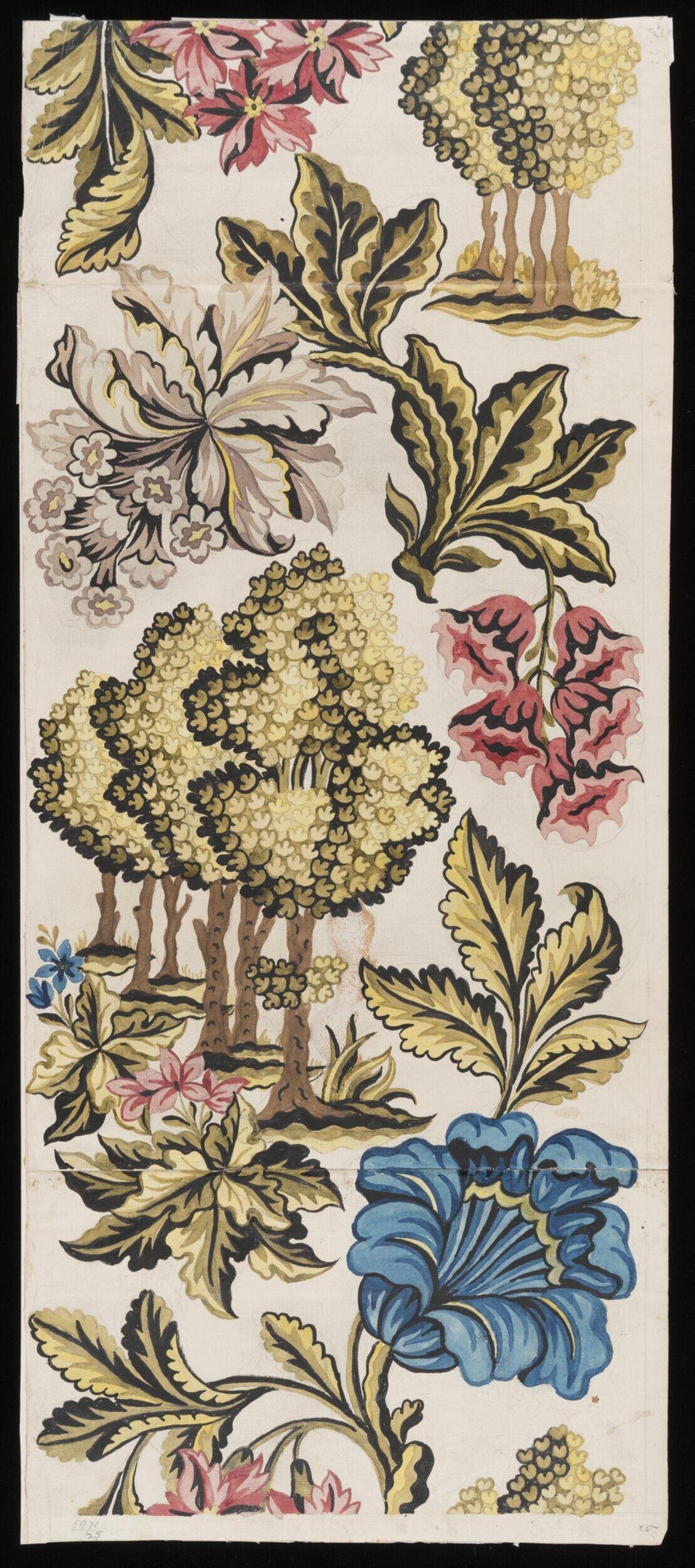

A simple design with fruit trees (above) appears to refer back to a papercut Anna Maria Garthwaite made in 1707, when she was just seventeen. This framed papercut is also in the V&A’s collection and shows a rural manor house at the edge of a village, enclosed by its formal garden and parkland. The image is packed with detailed observations of trees, houses, hedges and fences, while the activities of gardeners, woodsmen and a herd of deer, bring a playful vitality to the composition. Here in this early work, Garthwaite’s graphic style is already full of confidence and charm.

Cut paperwork by Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1707

Cut paperwork by Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1707 (detail)

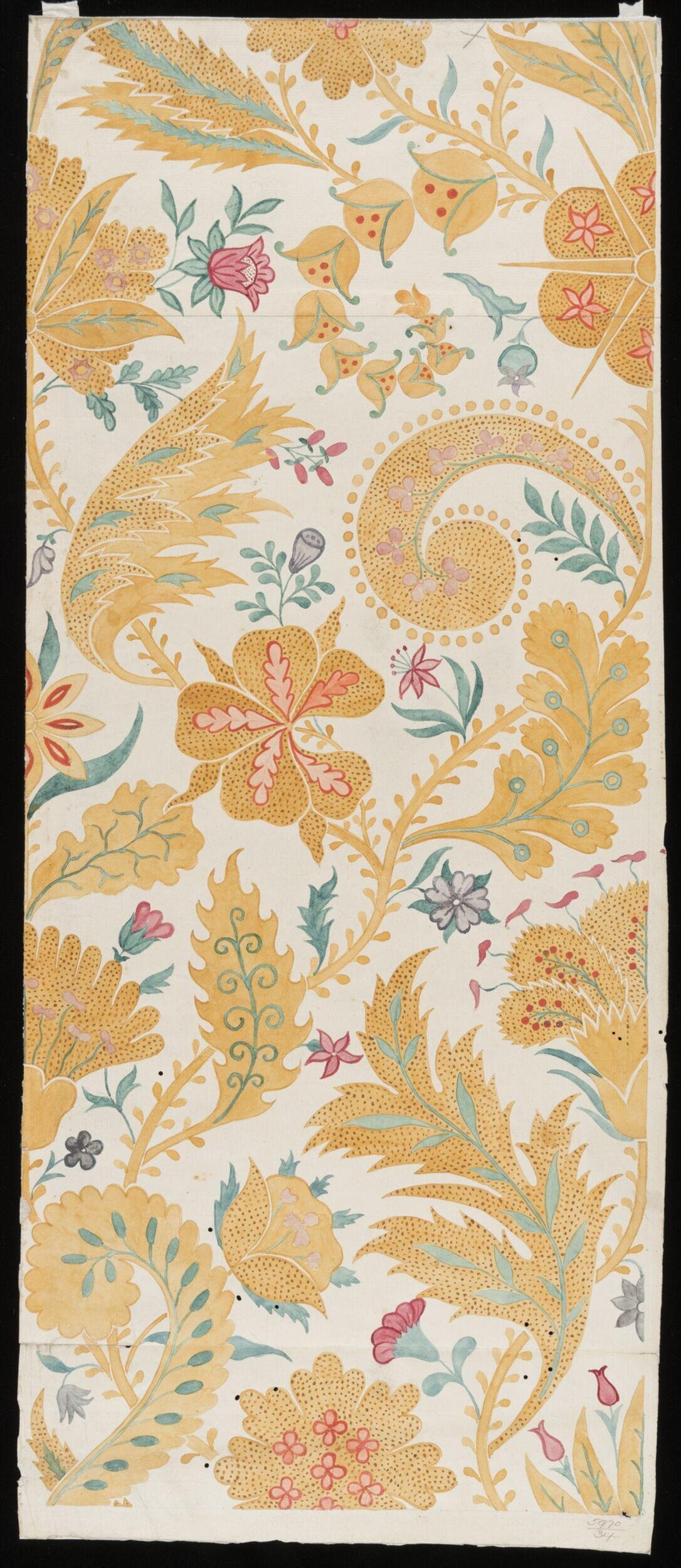

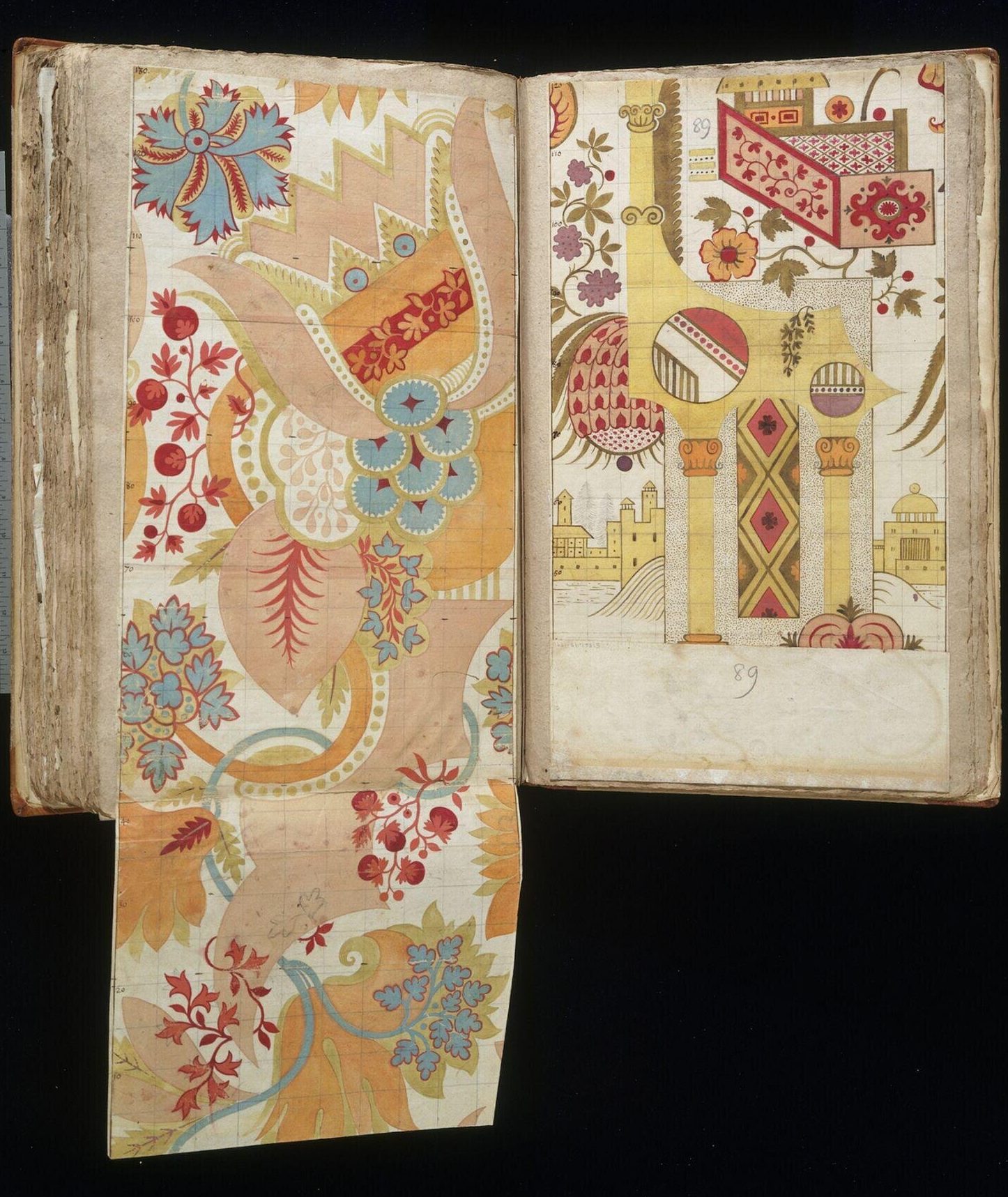

From the late 17th century until the early 18th century there was a trend across Europe for ‘bizarre silks’ characterised by large, often asymmetric patterns and highly stylised exotic fruits, flowers and palaces, all suggesting faraway places and reflecting the influence of new textiles and ceramics arriving in England from India and the far East. In Spitalfields, designer James Leman (1688 – 1745) was at the forefront of this style, producing bold, colourful designs. Here are some examples of Leman’s work from the V&A Collections.

Design for woven silk from the ‘Leman Album’, pencil, pen and ink, watercolour and bodycolour on laid paper, by James Leman, Spitalfields, 1709

Design for woven silk from the ‘Leman Album’, pencil, pen and ink and watercolour on laid paper, by James Leman, Spitalfields, 1708

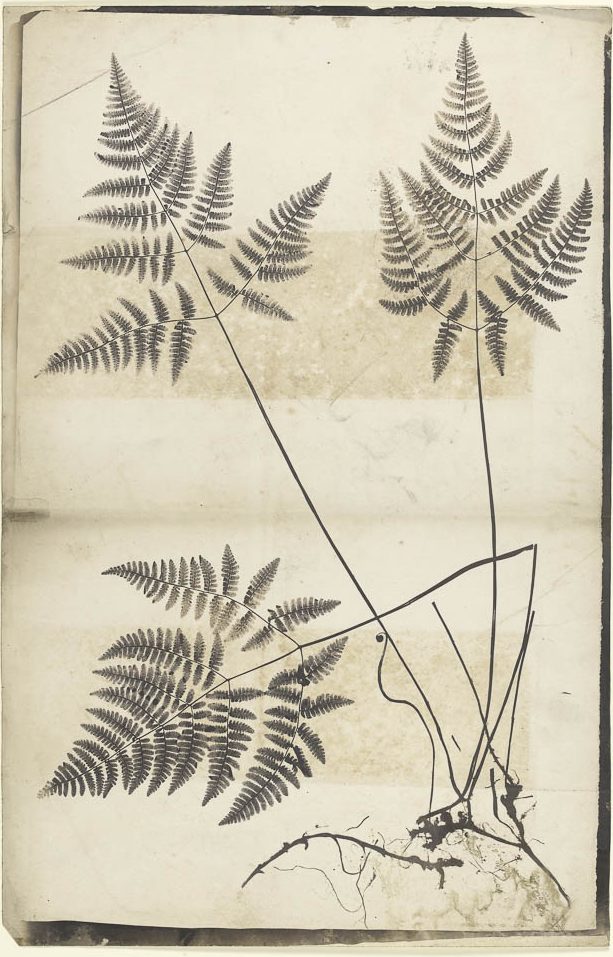

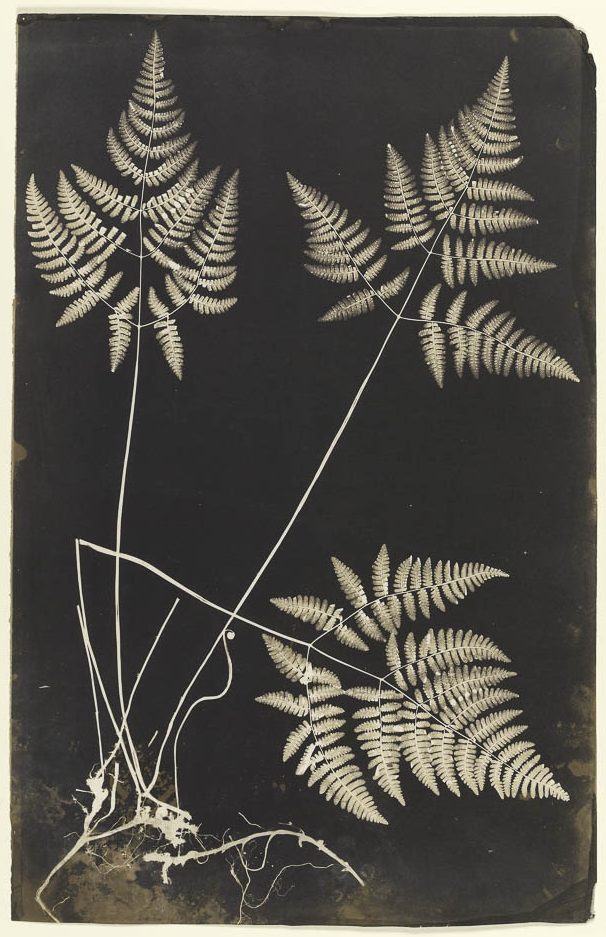

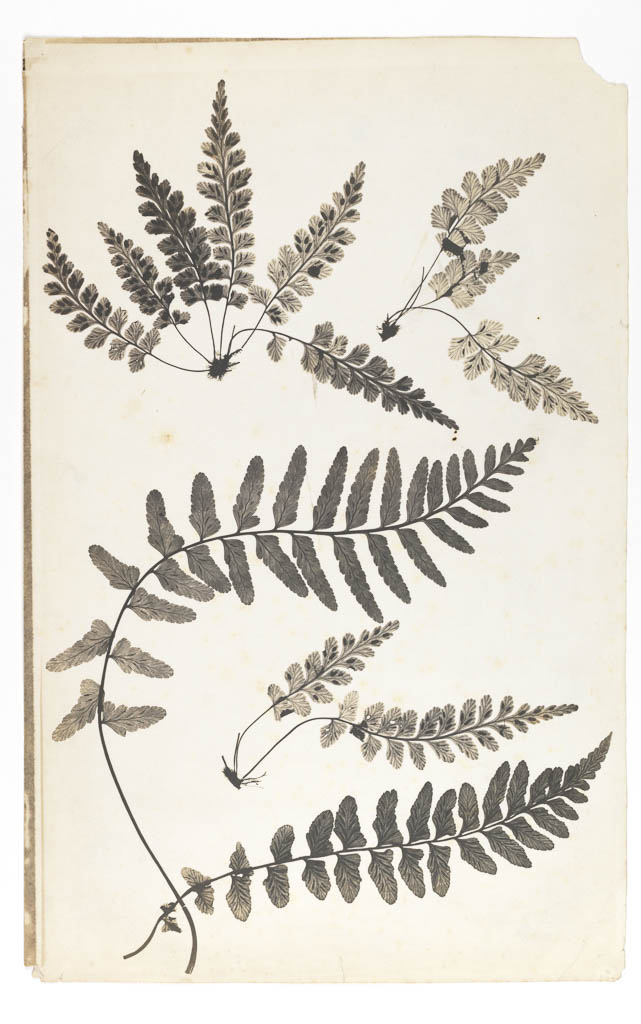

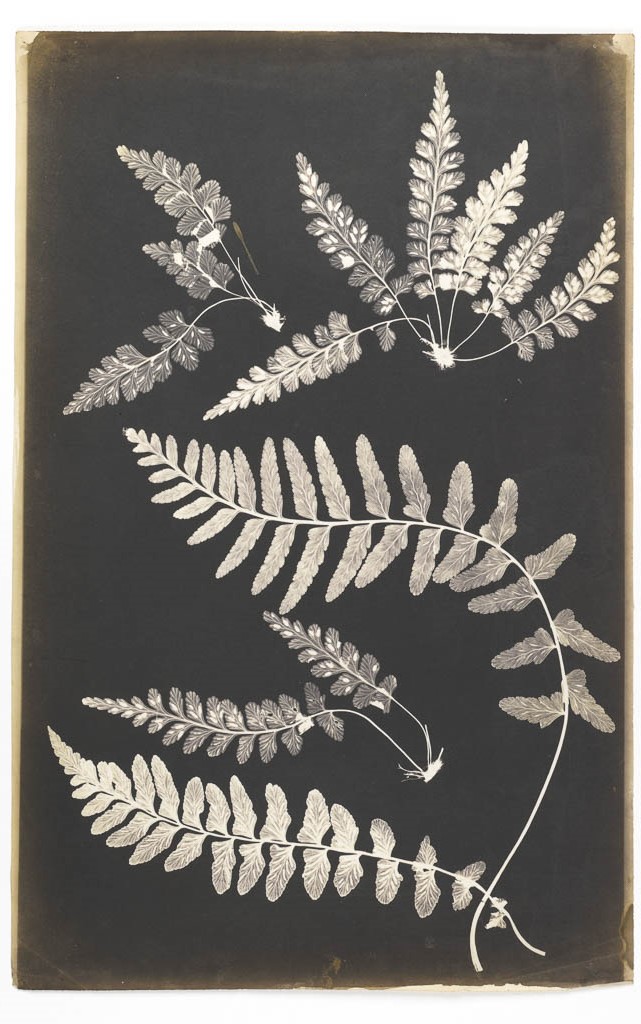

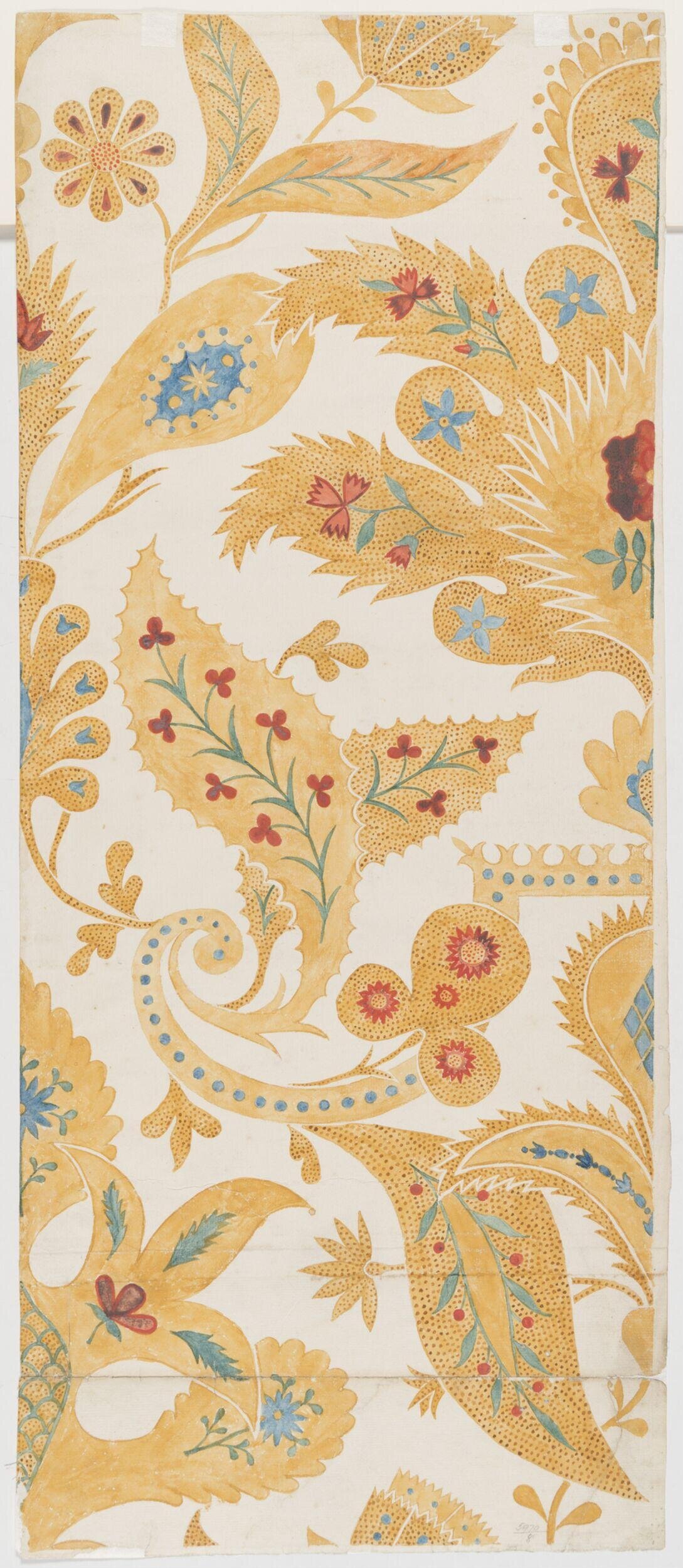

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1726-1727

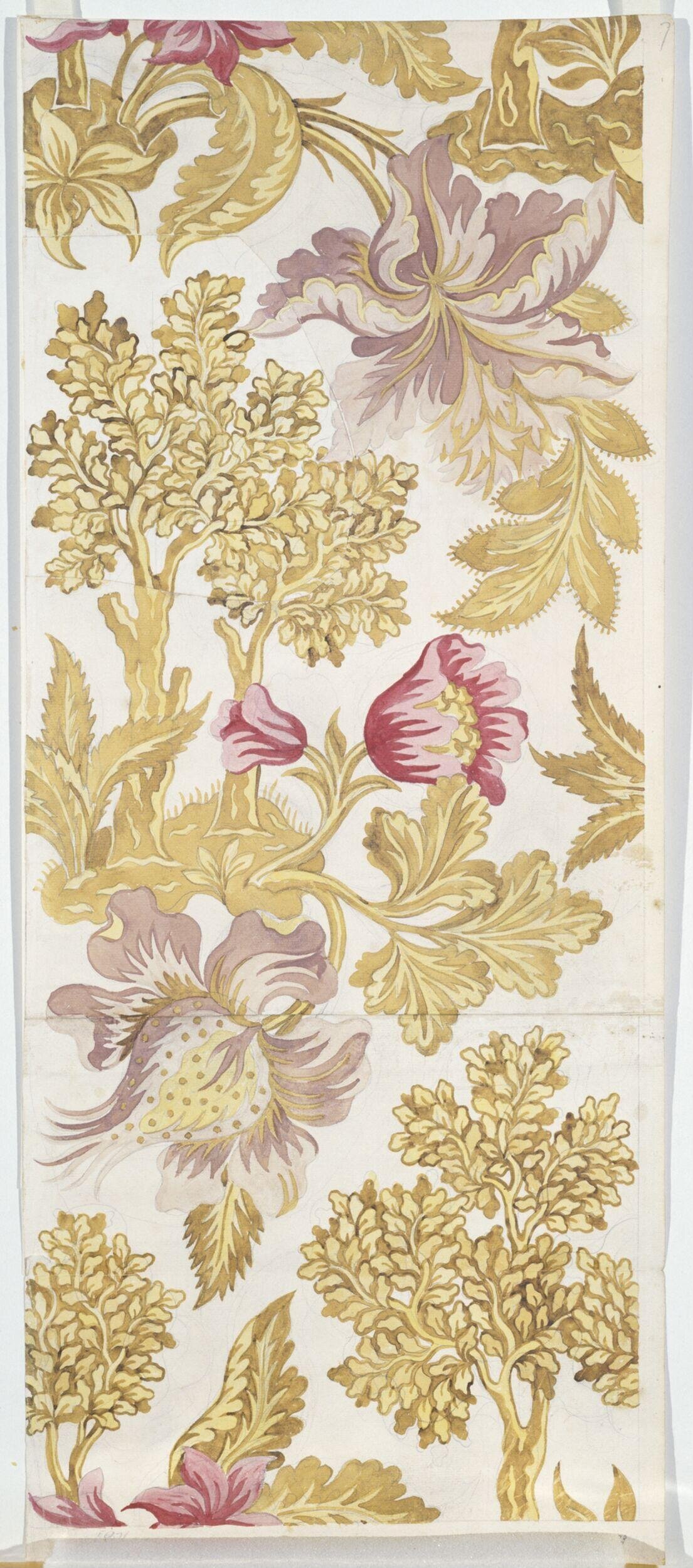

Before her arrival in London, Garthwaite produced patterns similar to the ‘bizarre’ style (see above), using a combination of scrolling organic shapes, decorated with popular flowers like dianthus and roses. In the years immediately after she moved to Spitalfields her designs appear more closely aligned with the work of local textile artists, like Leman, presumably as she became familiar with the fashions of the London market. Her use of contrasts and highlights made objects appear more three dimensional and the range of colours she used became darker and bolder.

Design for woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1729

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1731-1732

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca. 1733.

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca. 1734.

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca. 1734.

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1735

Design for a woven silk by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1730 – 1740.

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1742.

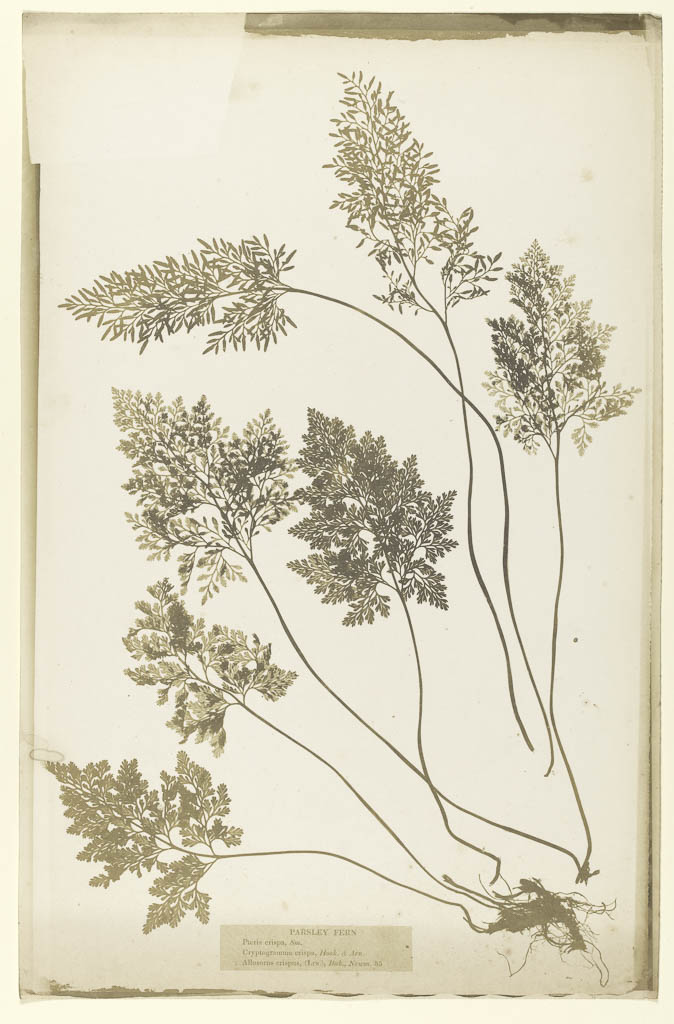

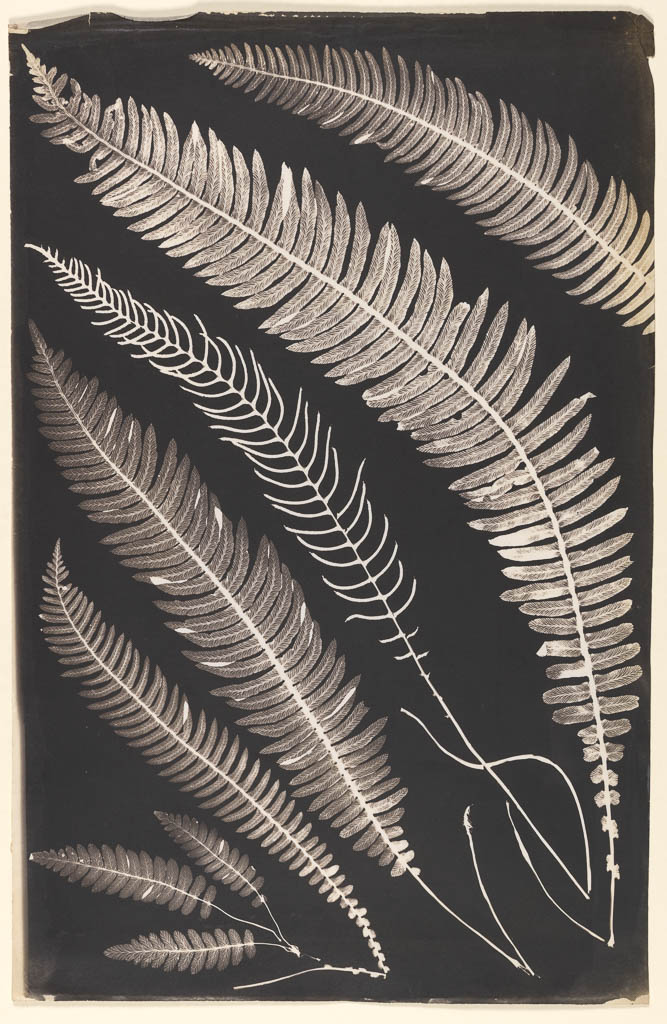

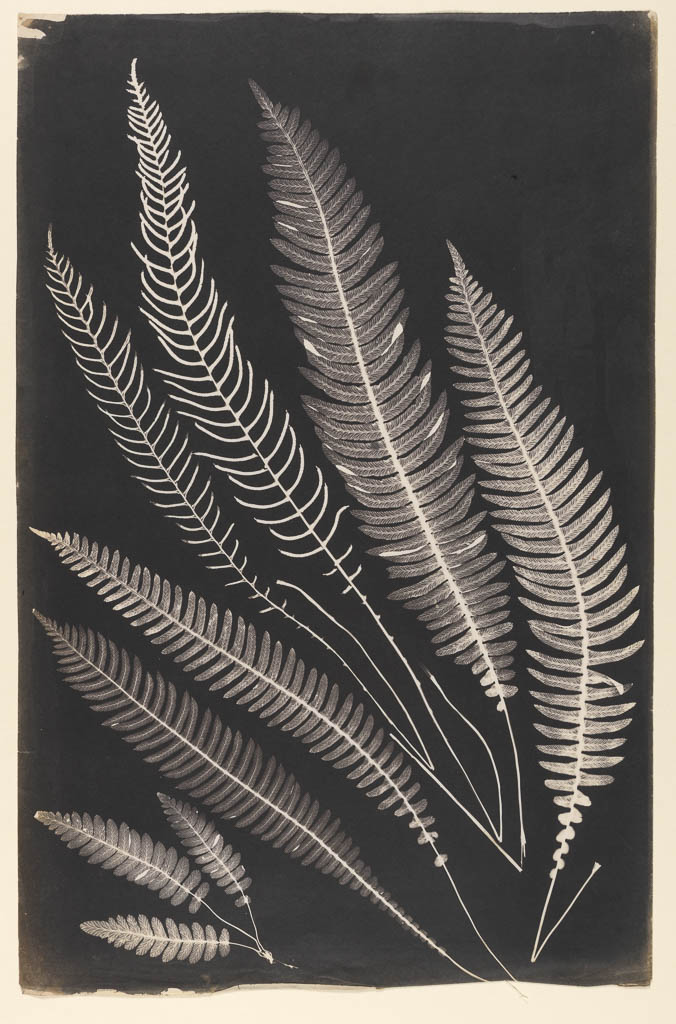

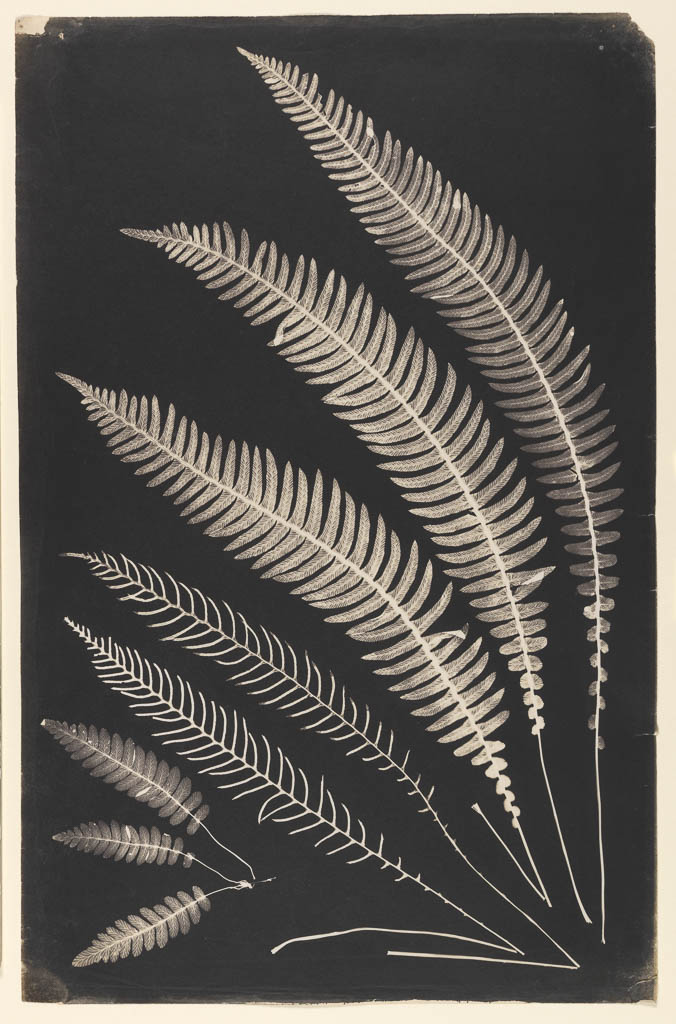

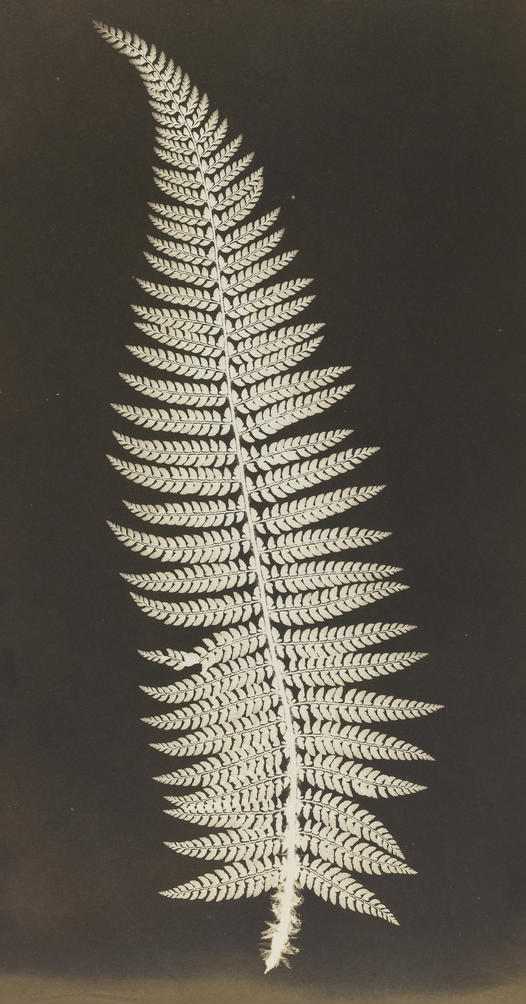

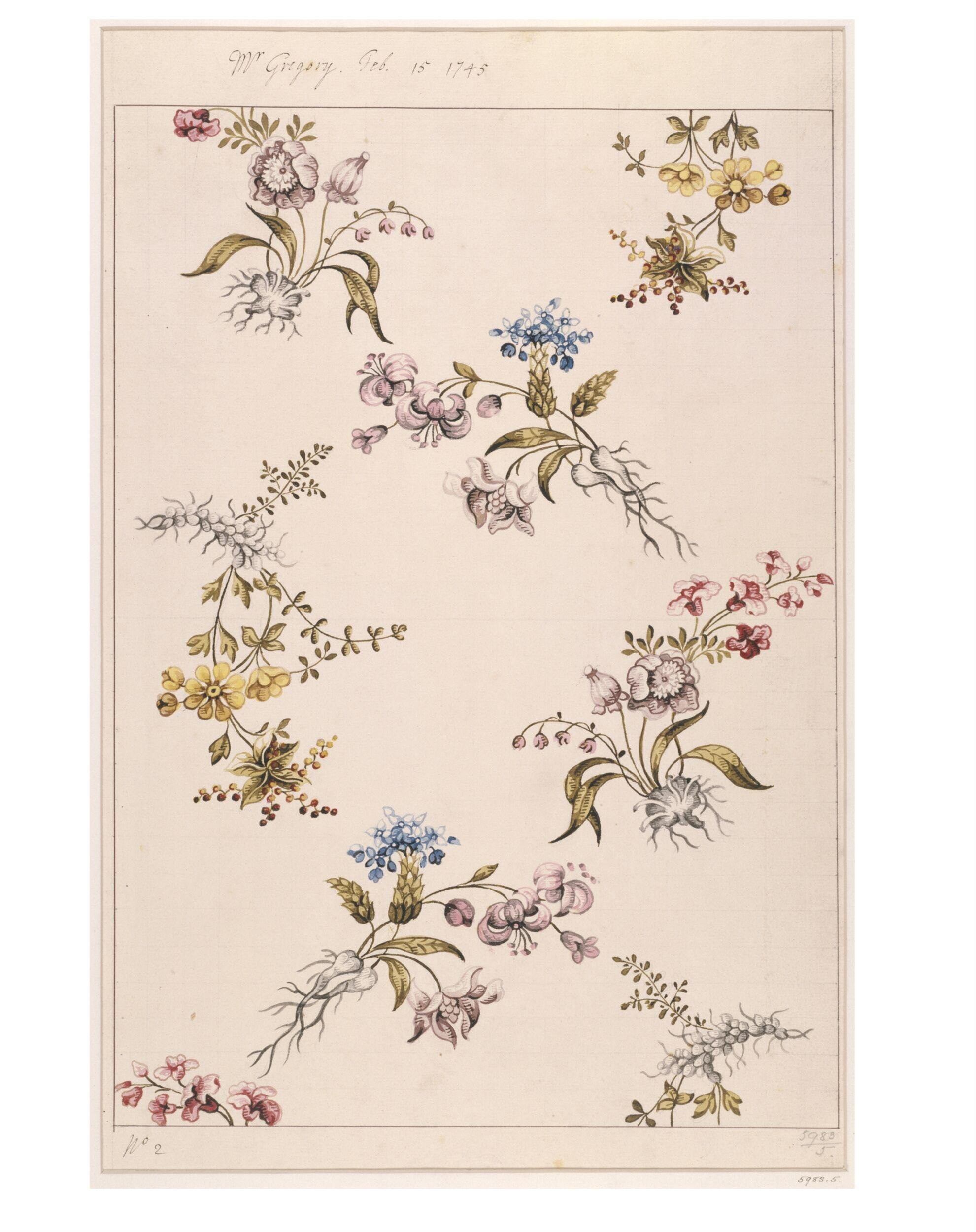

The 1740s saw a new fashion for woven silks with a naturalistic botanical theme, and Garthwaite excelled at these delicate designs. Some patterns are based on the form of a single species of flower, like the design above that uses the natural shape of anemone flowers stems and buds. Other designs use a combination of specimens carefully placed to make the pattern.

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1747.

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca. 1745.

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, ca. 1745.

Garthwaite also used closely observed elements from different plants to construct composite specimens that appeared life like, but impossible in nature. In the example above, a single root nodule towards the right of the image appears to support several unrelated leaves and flowers. Further down in the image two seemingly identical roots bear three quite different flowers.

In the design below, the branch that forms the structure of the pattern appears to bear six different species of flower. It’s interesting to see that in the final woven design the branches are green, instead of Garthwaite’s original choice of brown.

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1748.

Dress fabric of brocaded silk, designed by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, London, 1748

Design for a woven silk made by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, 1742.

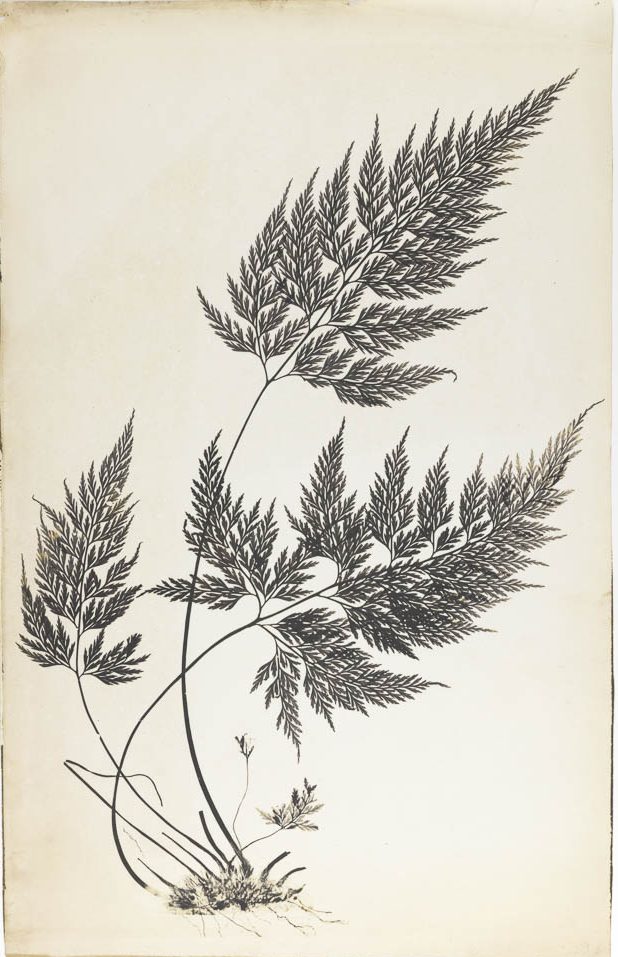

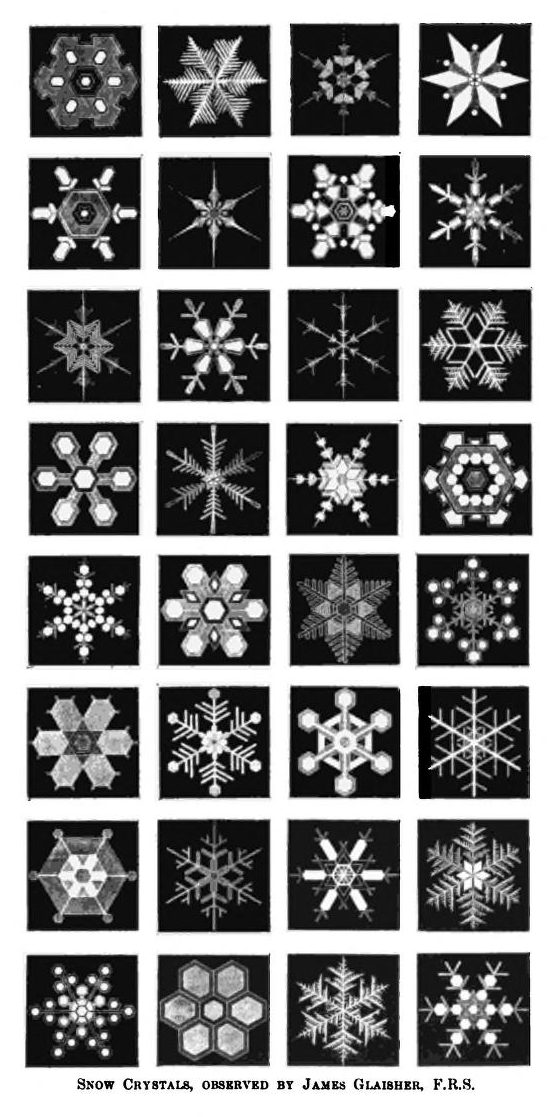

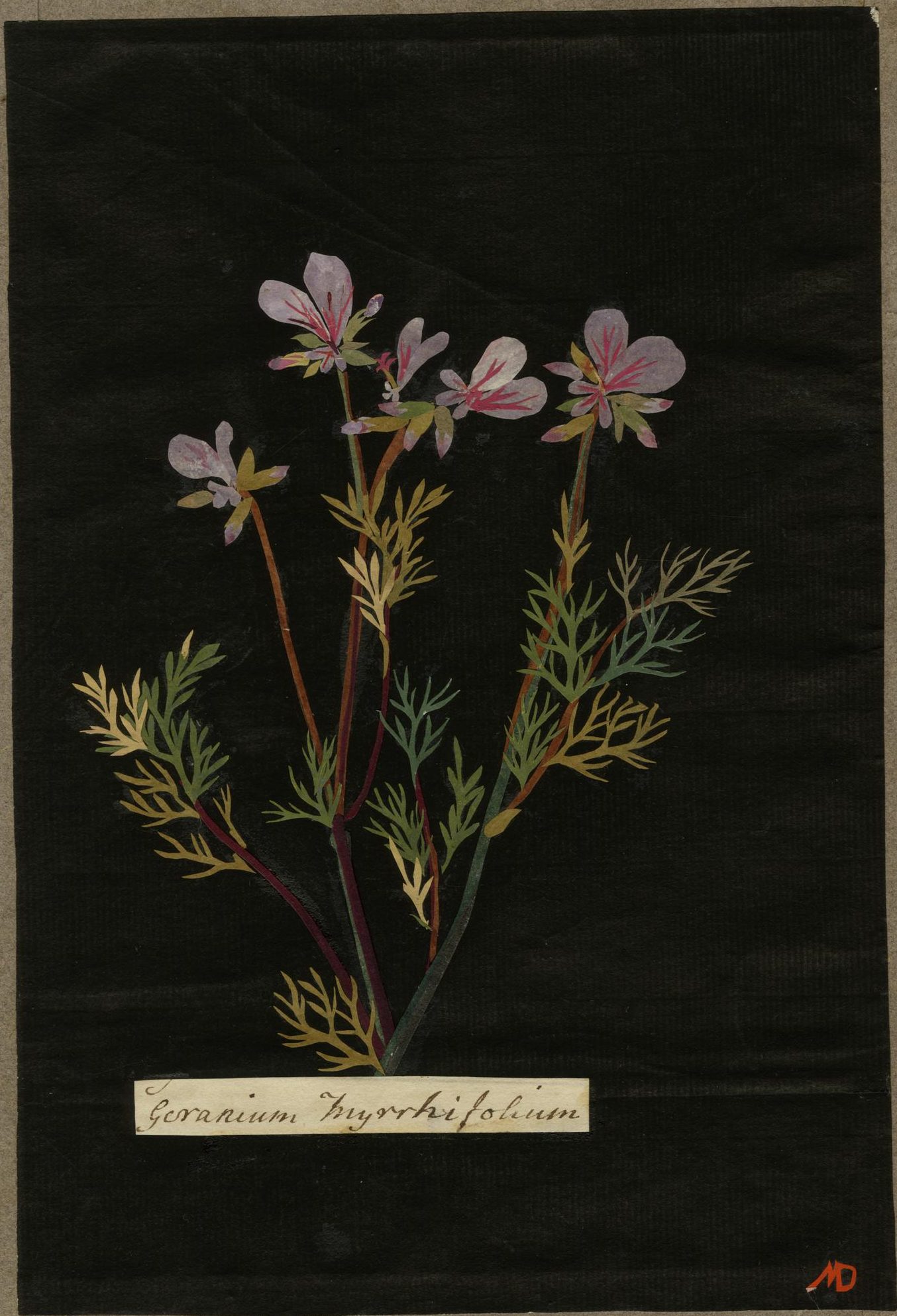

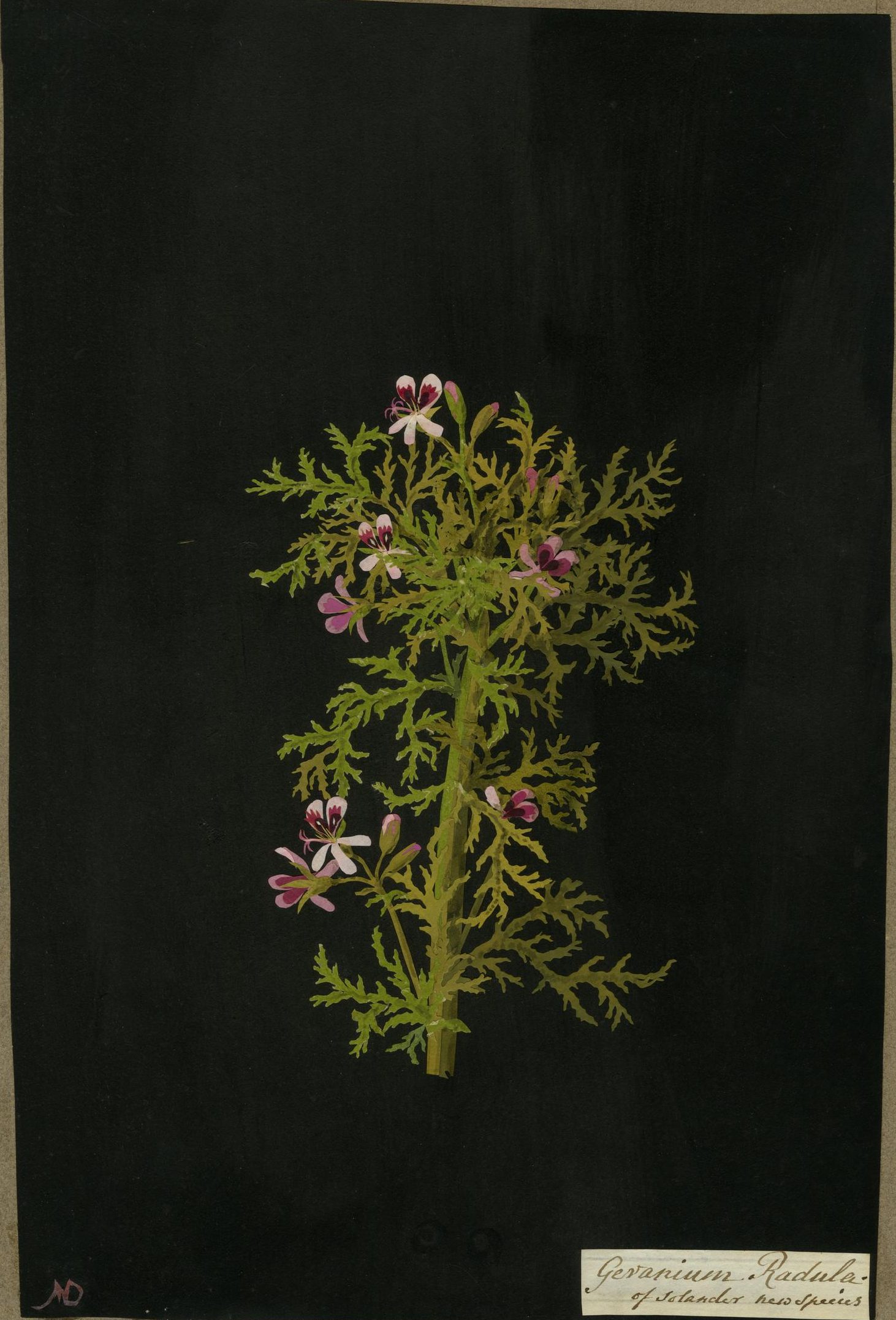

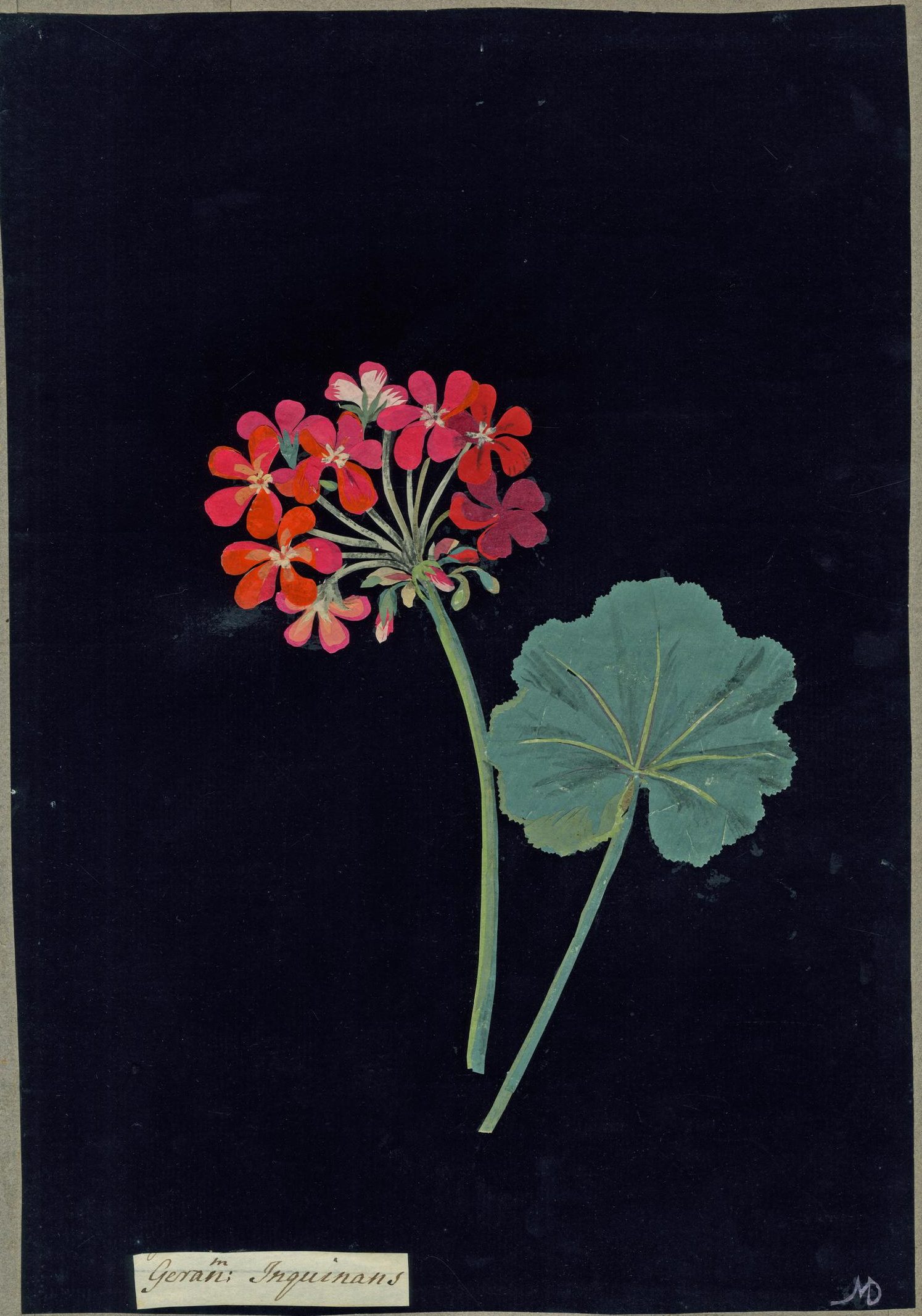

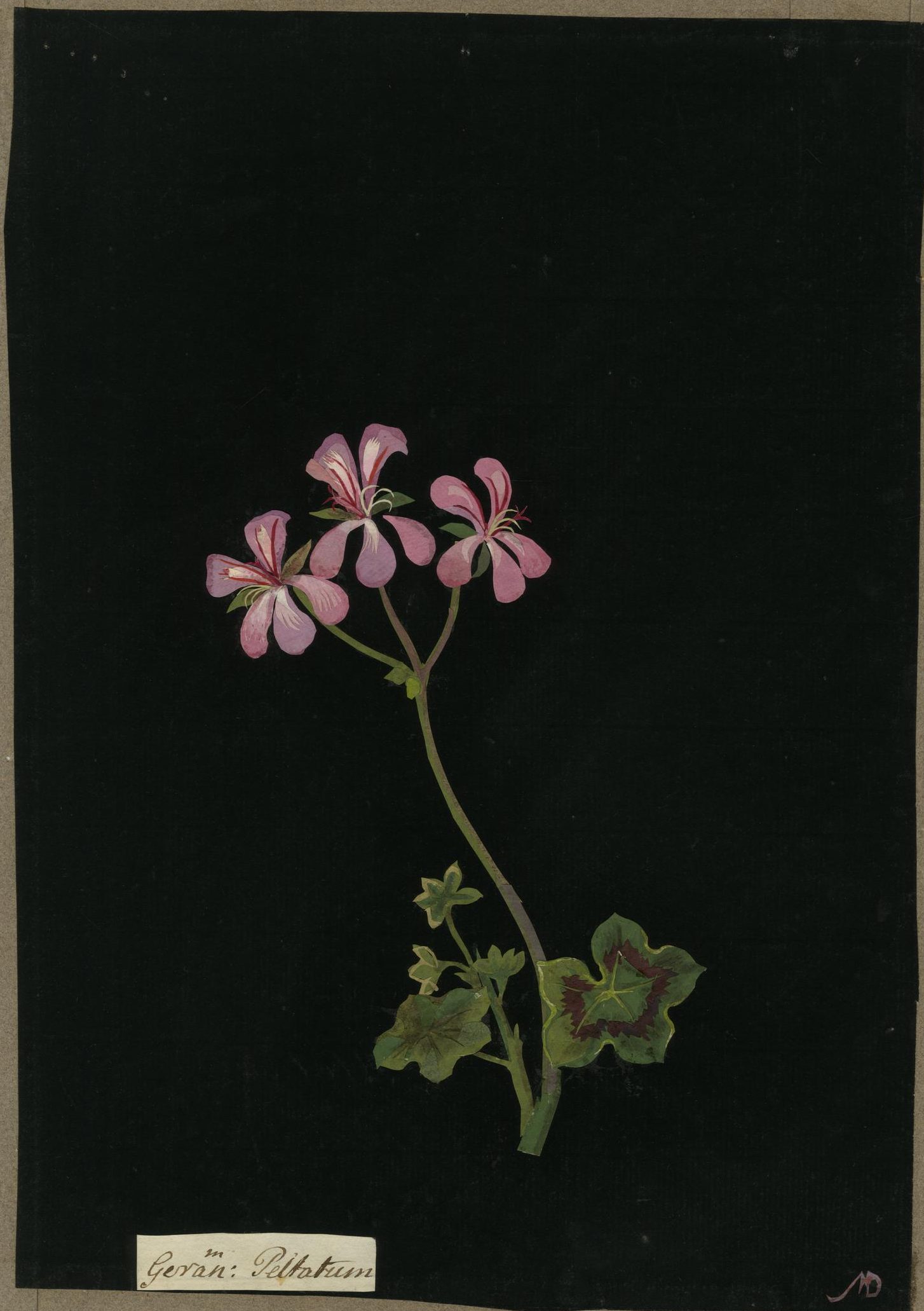

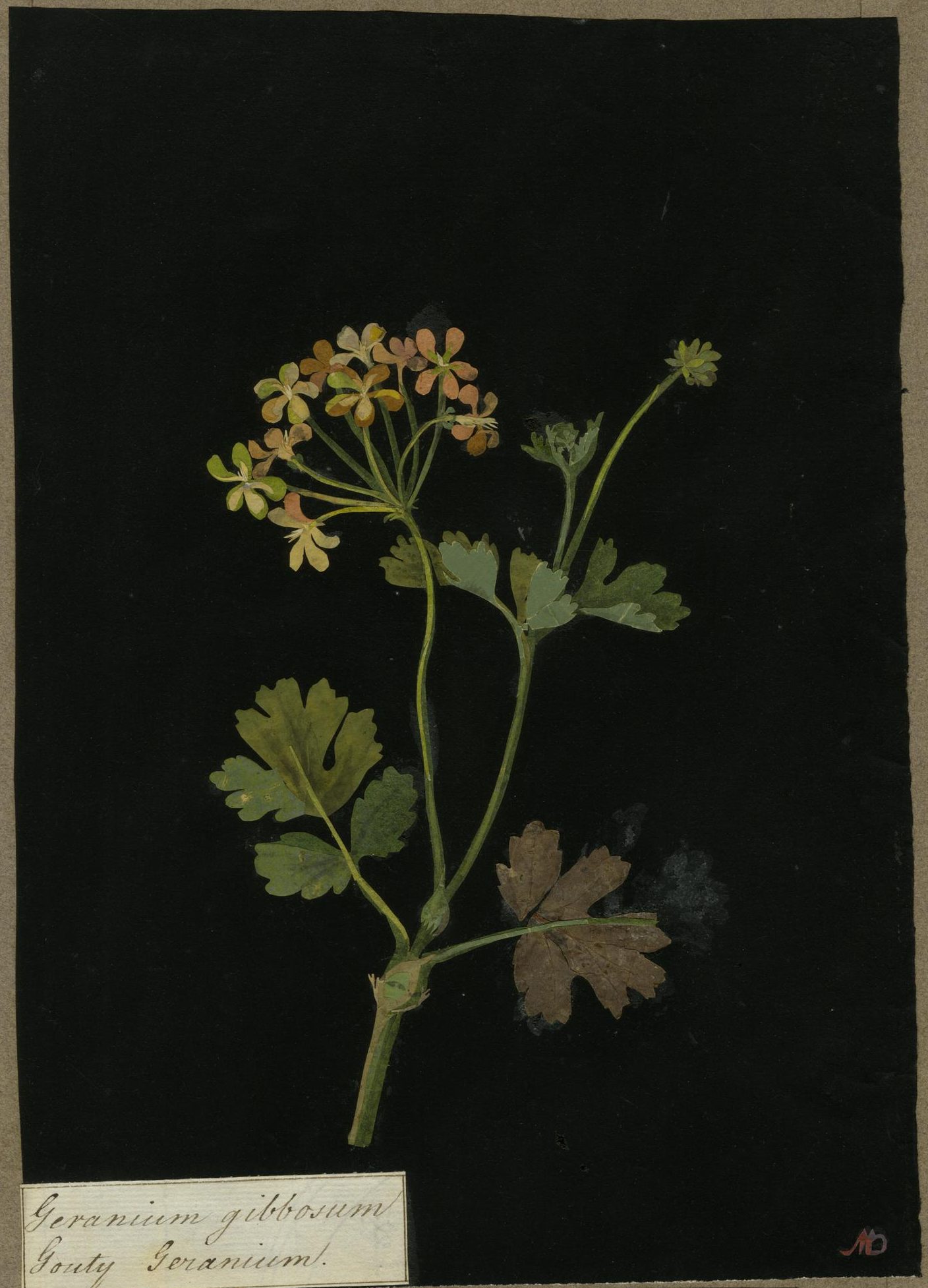

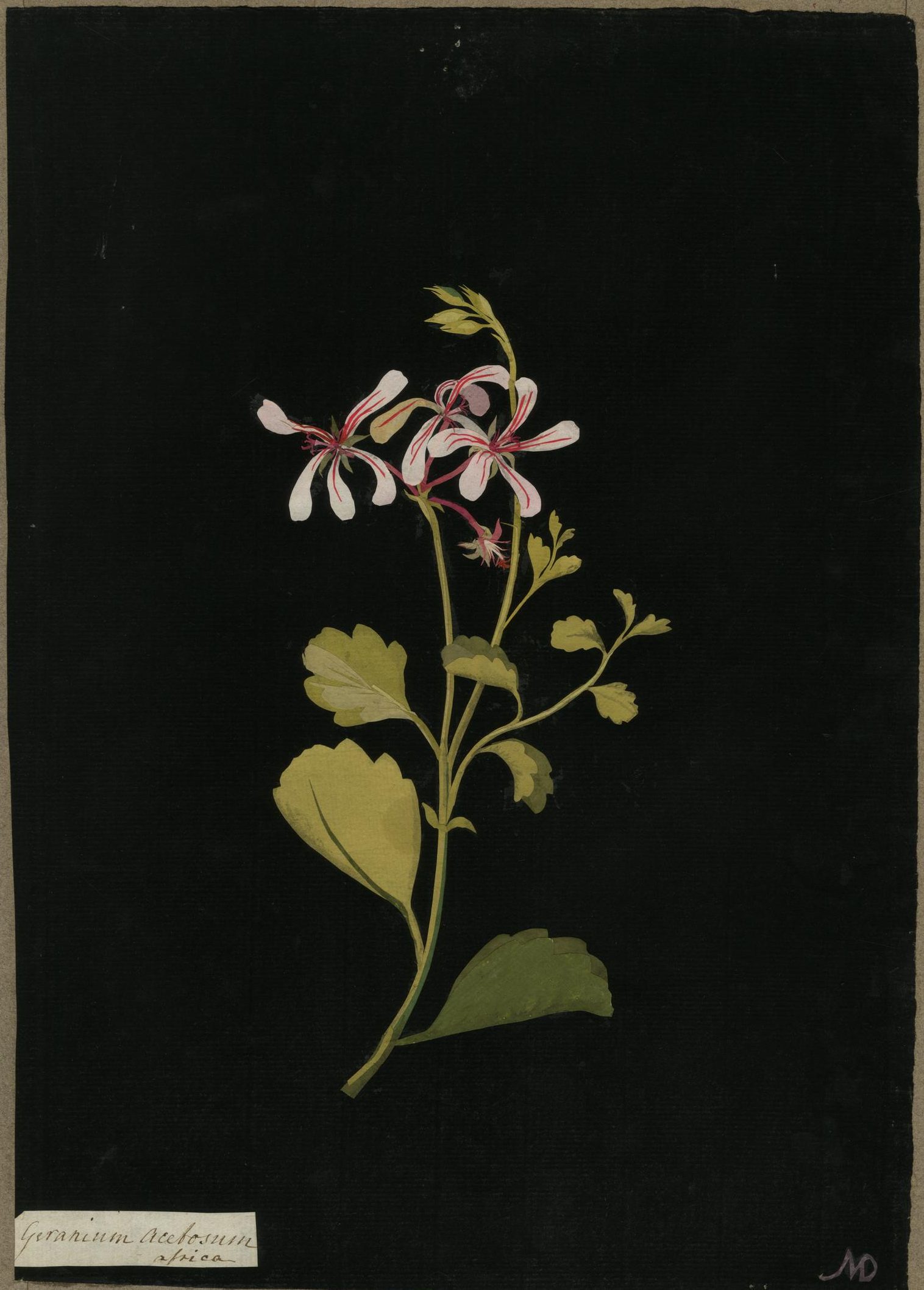

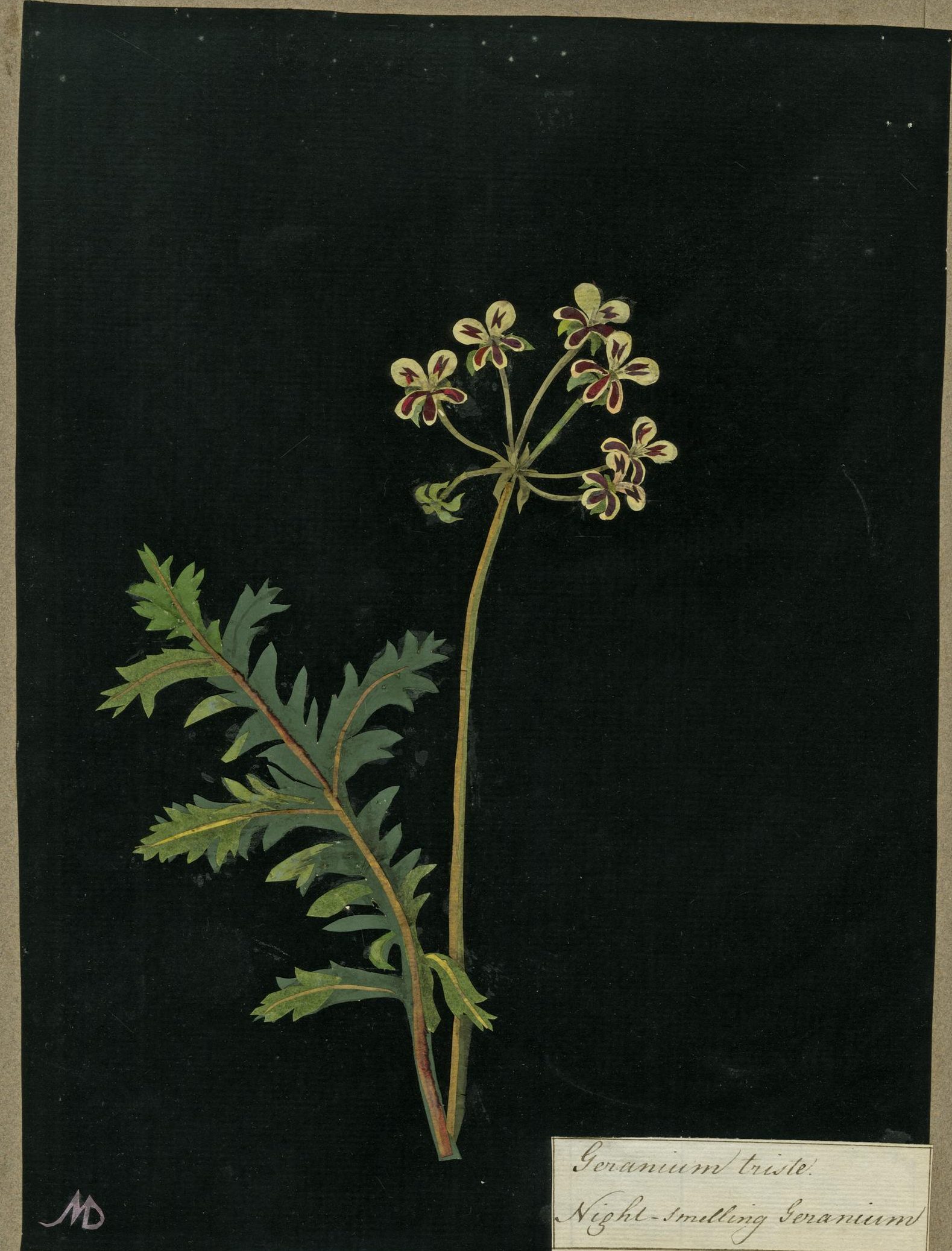

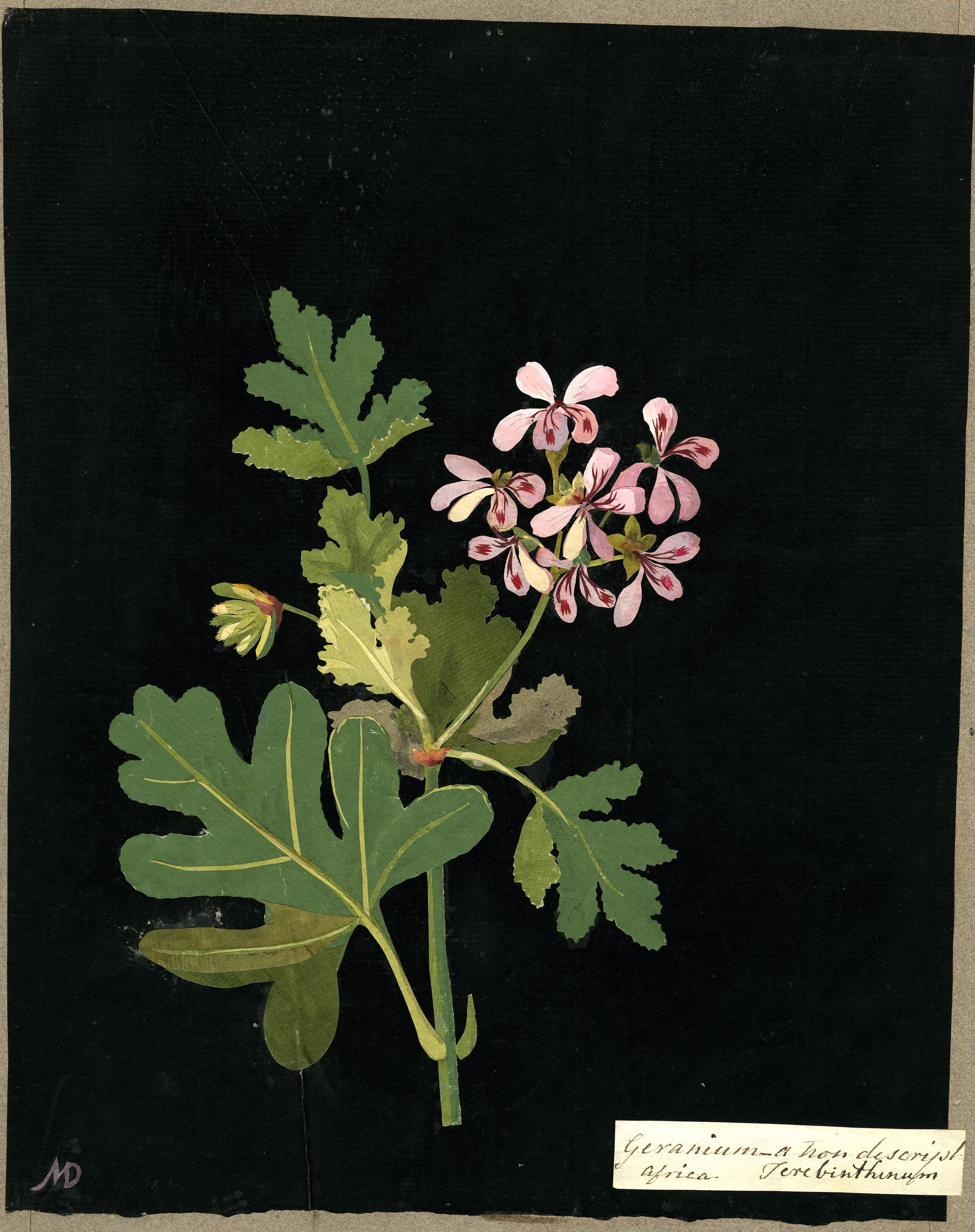

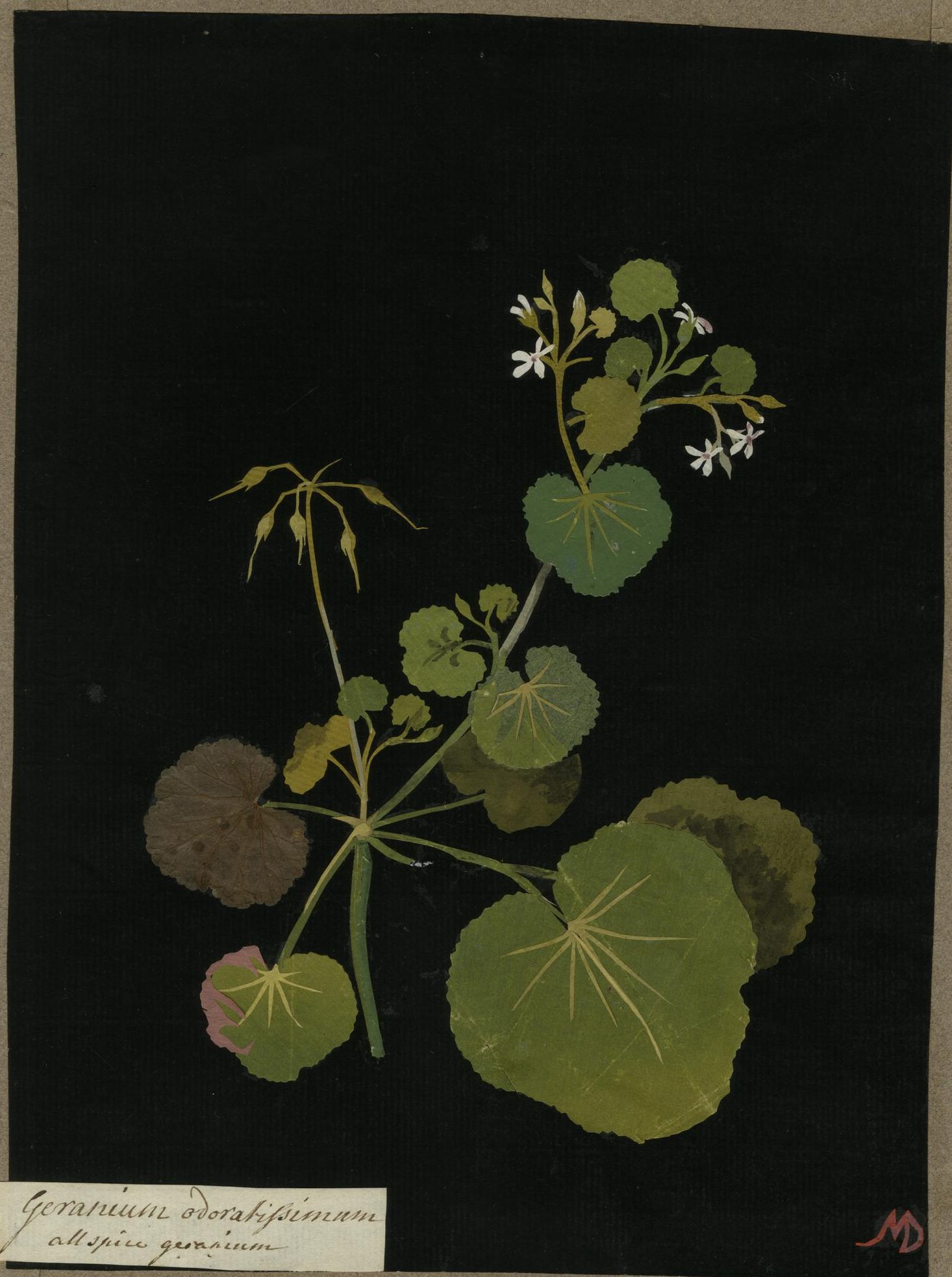

There has been some speculation about where Garthwaite and other designers might have found inspiration for the ornate floral elements that populate their designs. Although Spitalfields is intensely urban today, in the 1700s it was at the edge of the city of London, next to open countryside. Here, amongst the fields and market gardens, was a local concentration of plant nurseries. In Great Garden Street, (now Greatorex Street), parallel to Brick Lane and just a few streets away from Garthwaite’s house, was a nursery on twelve acres managed by Leonard Gurle selling over 300 fruit trees, and an array of garden plants including many imported rarities. Further east at Mile End was Mr Clements who specialised in vines.

To the north in nearby Hoxton were nurseries belonging to James Ricketts, William Darby and George Pearson. Pearson specialised in anemones while Darby supplied shrubs and rare greenhouse specimens and ‘kept a folio paper book in which he pasted the leaves and flowers of almost all manner of plants, which made for more accurate identification than the woodcuts reproduced in herbals’. All these establishments with their glasshouses filled with exotic plants would have been a treasure trove of material for the botanical artist.

In any age, the challenges for the commercial artist to keep pace with new ideas, changing fashions and technological innovations are immense, and although Garthwaite continued to produce designs into the 1750s she didn’t enjoy the same level success as in earlier years. However, we are fortunate indeed that so many of her designs have survived, and her career in textiles can still be appreciated today.

The designs by Anna Maria Garthwaite featured here are just a fraction of those in the V&A’s collection – well worth browsing more via the link below. There’s also much more information about the nurseries of East London via The Garden History Blog and the Hackney Society – links below.

Further reading:

Anna Maria Garthwaite Collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum here

Anna Maria Garthwaite Wikipedia here

Spitalfields Life: At Anna Maria Garthwaite’s house here

The Garden History Blog: London Nurseries in the 1690s here

The Hackney Society: Horticultural Hoxton here

James Leman Collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum here

Bizarre silks Wikipedia here