Poppy by Constant Alexandre Famin, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

Today, if an artist needs visual reference for any plant, whether it’s the form of a leaf, or a flower or seed pod, it’s available instantly in a matter of seconds, via the internet. At the same time, gardening books, magazines and catalogues, also packed with photographs, assist with identification and remind us how a vast array of plants actually look.

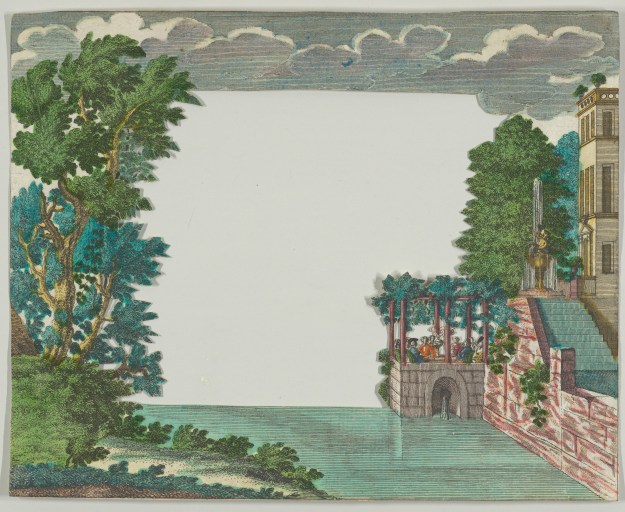

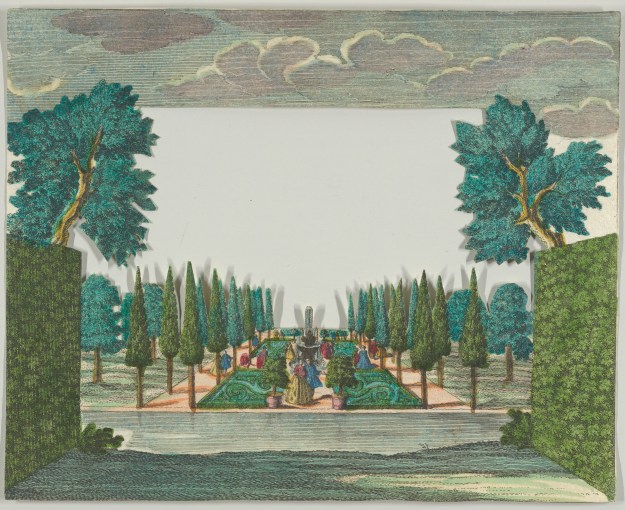

We’re so accustomed to the availability of these botanical resources, we take them entirely for granted, but in the 1860s, when these photographs of foliage and flowers were taken, those who worked in creative industries had to rely on physical specimens (if they were in season) or drawings, woodcuts and engravings as references for their work.

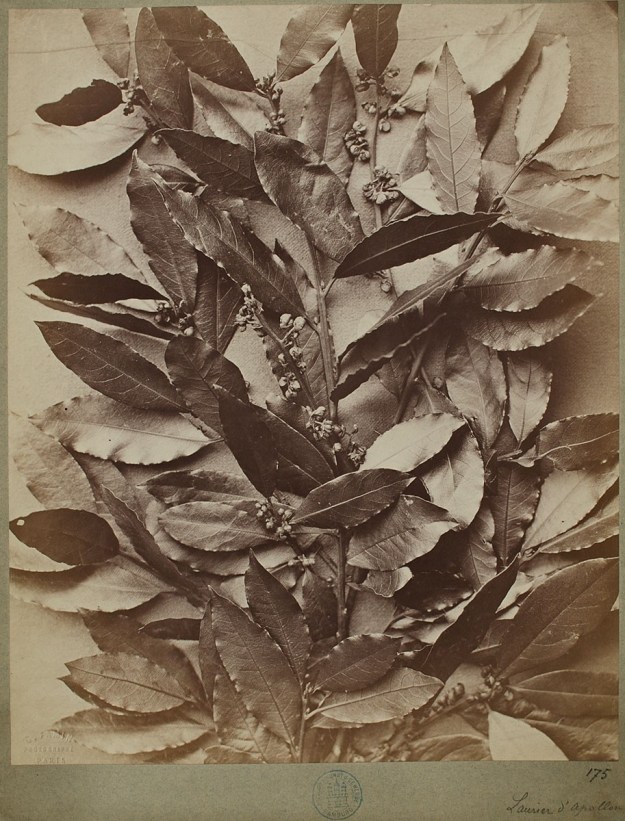

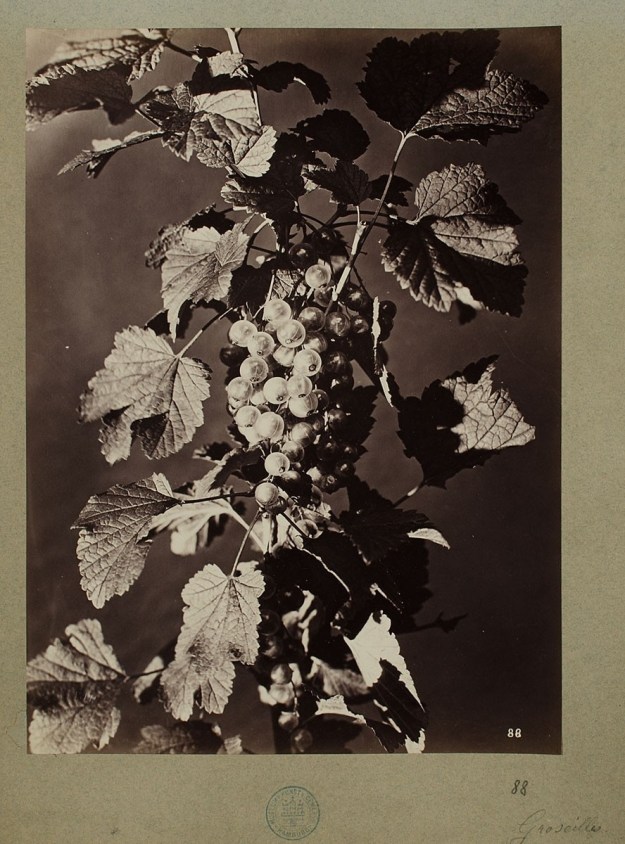

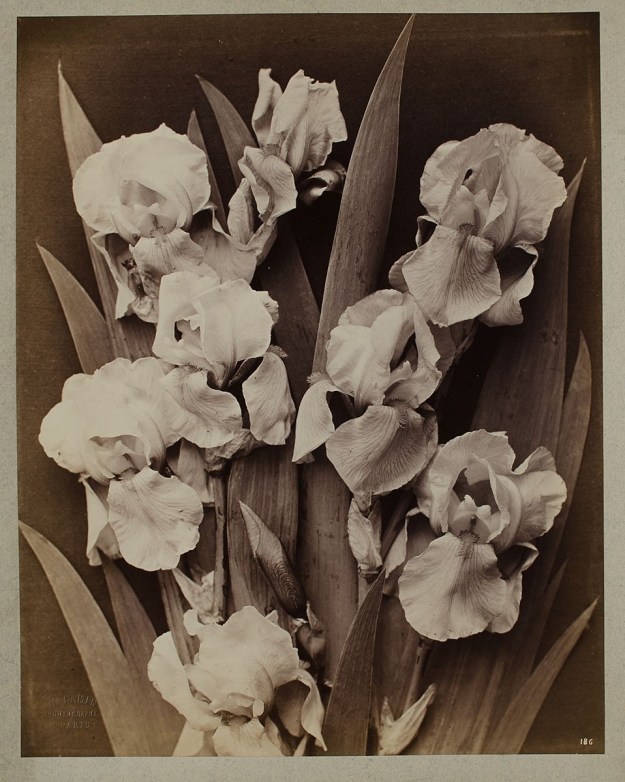

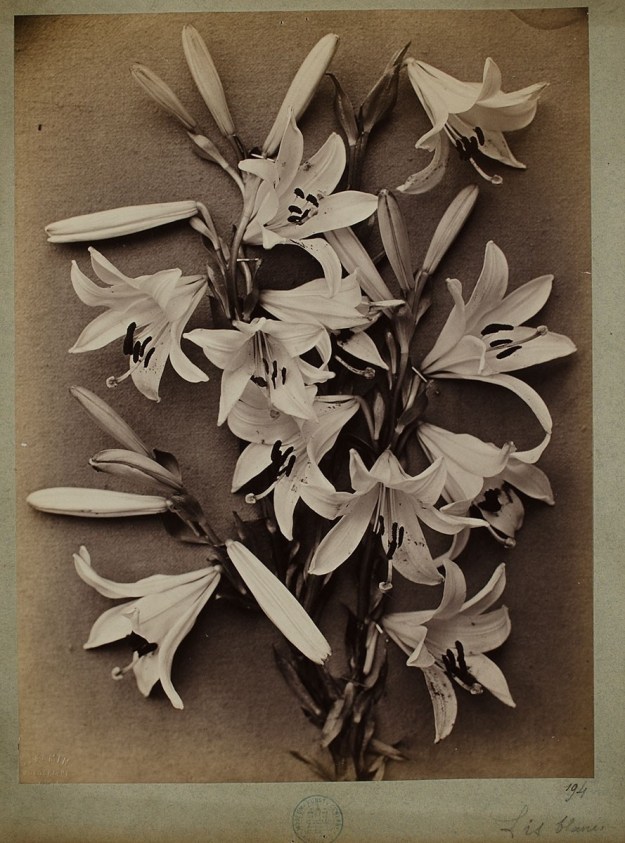

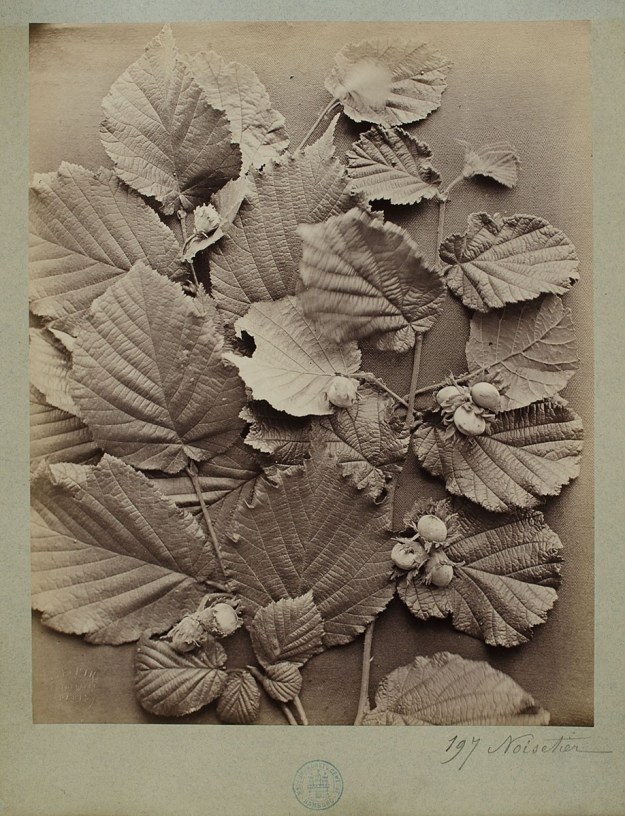

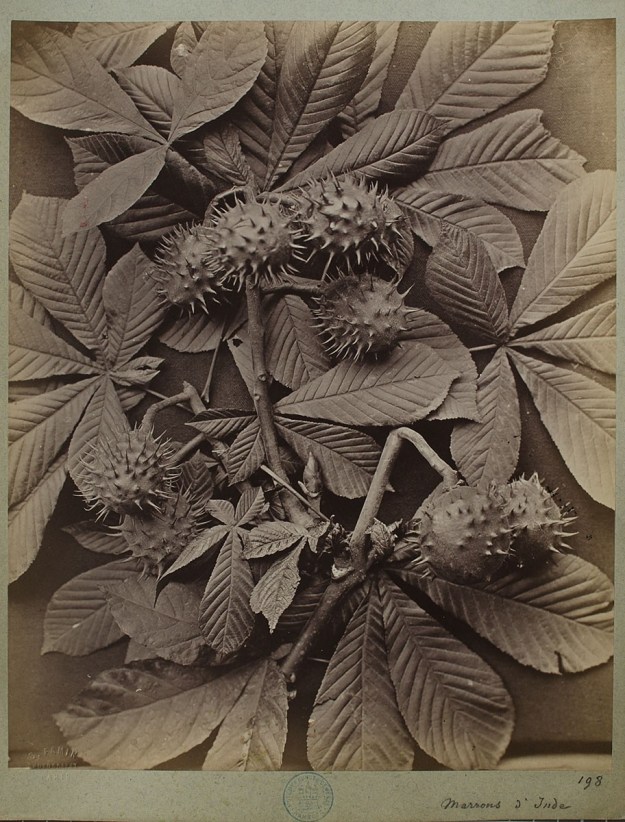

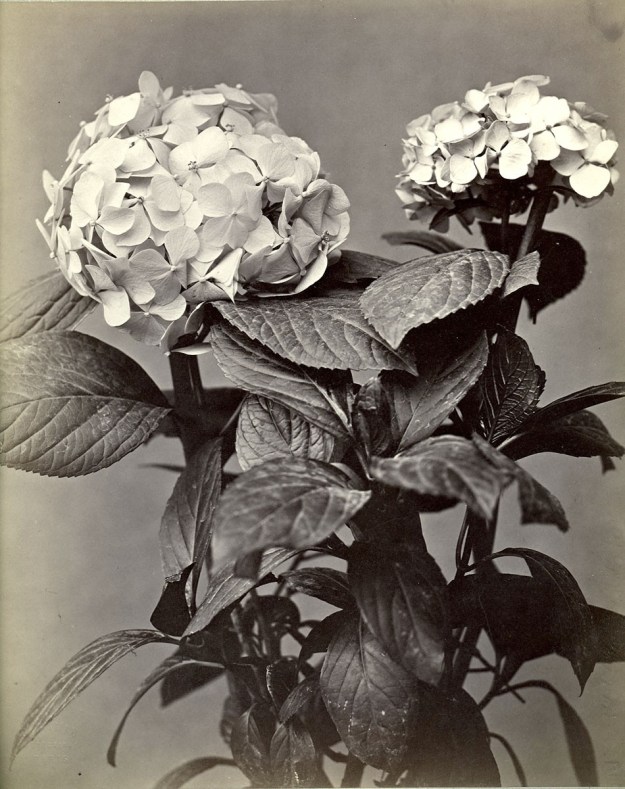

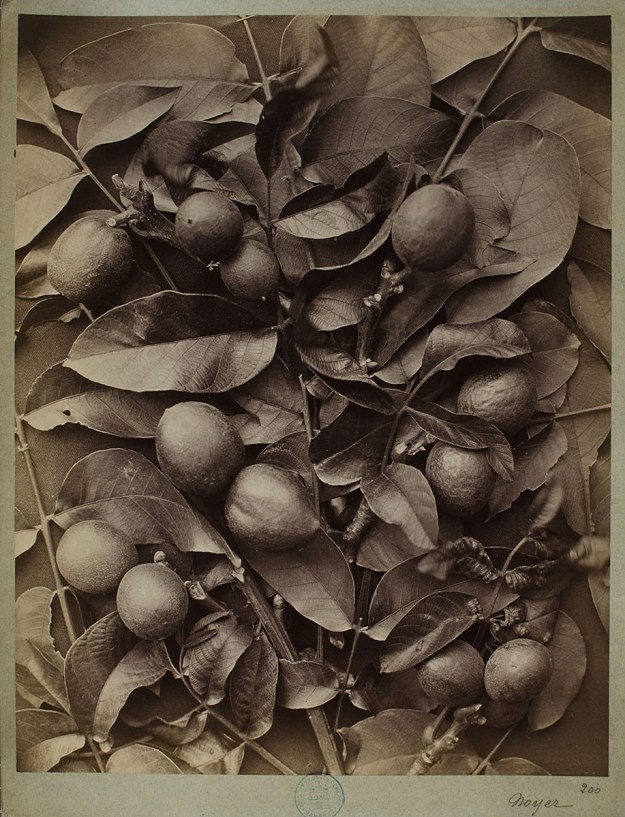

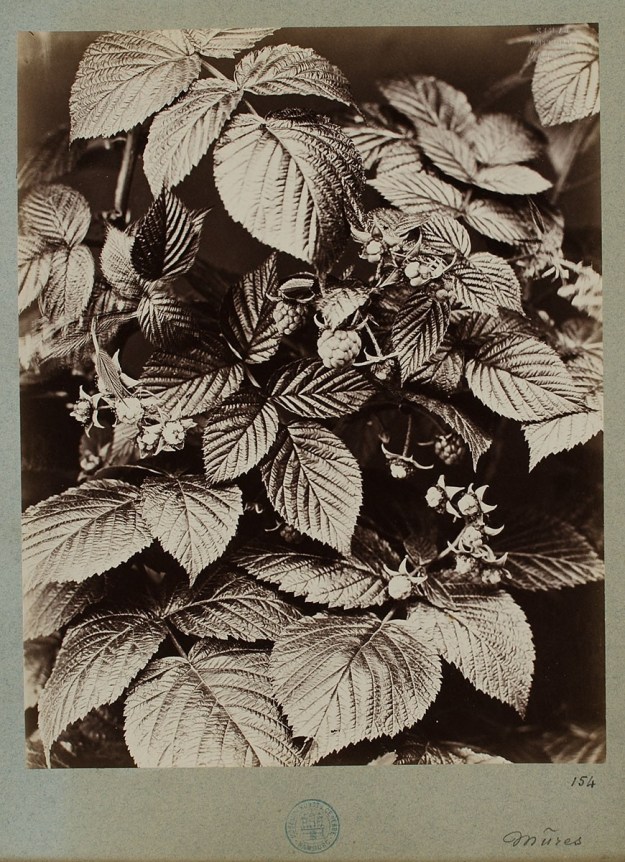

Famin’s innovative plant themed photographs were aimed at artists and craftspeople, giving them year round access to accurate and detailed reference images of plants. Each image, taken from a glass negative, was printed onto paper and mounted onto cards – perhaps easier to use in the studio than propping open a book or folder. For fragile flowers like iris, lilac and poppies, with their complicated forms and fleeting blooms lasting just a matter of days, these photographs would have been especially valuable at times when living specimens were unavailable.

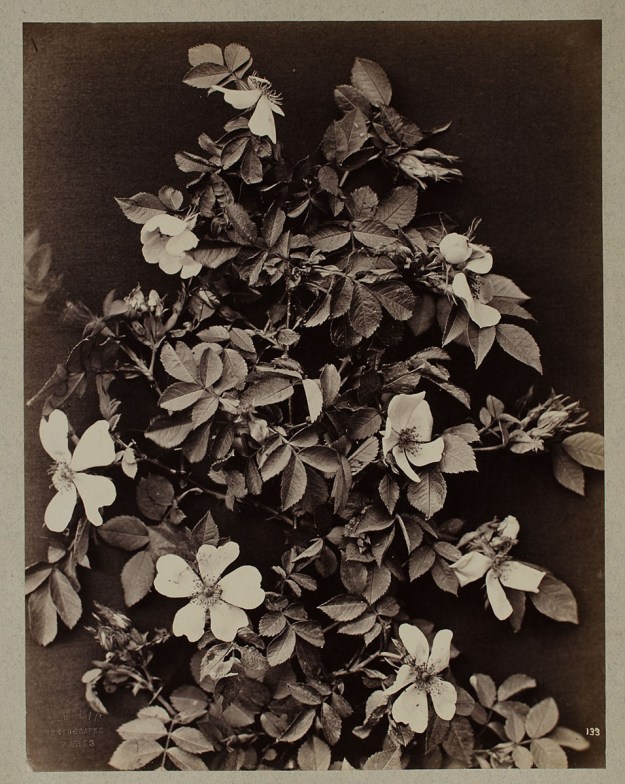

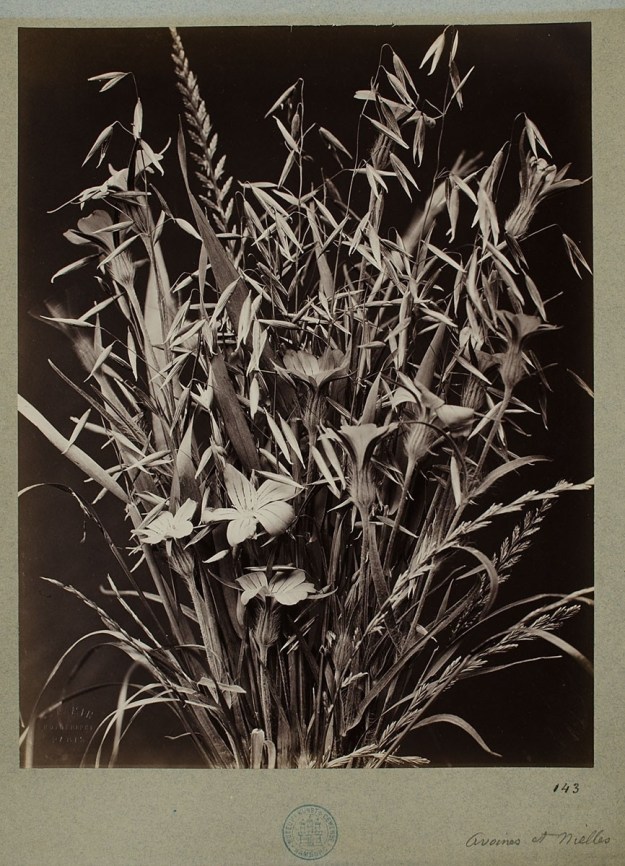

Typically in this series, Famin arranges multiple stems from the same plant and photographs them so that they fill, or sometimes spill over, the edge of the frame. The effect is to produce a sense of intensity; for a moment, as we view each image, we are overwhelmed with the special character and presence of each plant.

One of the most evocative photographs depicts a sheaf of oats and corncockle flowers, an annual weed of arable fields, seeming to shimmer against a dark background. The sheaf also contains what appears to be crested dog’s tail grass, demonstrating the diversity of plants present in crops before the widespread use of selective weed killers.

Even though examples of his work are held by some of the world’s leading museums, information about the life of French photographer Constant Alexandre Famin (1827 – 1888) is sparse. We do know that Famin had a commercial photography business with two studios in Paris, producing images of parkland, the countryside, and examples of architecture as reference for painters.

The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg has twenty four examples of Famin’s still life plant images in their collection, but judging from the numbering at the bottom of each of these, there appear to have been at least 200 photographs in the series. A brief online search reveals more of Famin’s plant images – photographs of hyacinths, hollyhocks and foxgloves appear from time to time in auction sales.

Judging by the seasonal variety of the specimens he recorded, Famin’s plant series must have been produced over the course of at least one calendar year. Beginning with spring flowering narcissus and apple blossom, the images continue with summer roses, poppies, strawberries and currants. A range of trees include oak, hawthorn and walnut, often with their late season fruits. Gathering the freshest specimens for the project must have taken some effort and meticulous planning.

Although there’s consistency to the composition across Famin’s botanical series, there’s also some variety in the images, reflecting the character of each plant. Light reflecting from the surface of blackberry, strawberry and holly leaves gives them an unexpected solidity, and a metallic quality. The sculptural spikiness of holly leaves, and the armoured fruit cases of the horse chestnut contrast with softer textures of hydrangea and fuchsia flowers. A magnificent opium poppy shows some unexpected motion blur in one of the leaves – perhaps it escaped from careful positioning during the long exposure. Looking now at these skillful photographs, they seem more than just reference, but artworks in their own right, representing plants in a new way.

Links to sources below.

Dog Rose

41. Apple blossom

56. Narcissus

Lilac

175. Bay

88. Red currants

127. Vine leaves

Iris

194. White lilies

173 Peach blossom

Hazel

170. Holly

198. Horse Chestnut

85. Hydrangea

Roses

143. Oats and corncockle

163. Oak leaves

29. Irises

200. Walnut

23. Fuschia

154. Blackberry

Sweet chestnut

148. Strawberry

Further reading:

Constant Alexandre Famin’s photographs at theMuseum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg here

Photo Central has some of Famin’s work for sale here

Biographical details at Monoskop here