Self-portrait in the garden

Salted paper print, 1847

All photographs courtesy of the J Paul Getty Museum (unless otherwise stated)

This remarkable image of a man standing in his garden was produced by Hippolyte Bayard (1801 – 1887), an early pioneer of photography. His record of people and the built environment around Paris, where he lived, provides a vivid insight into the character of cultural life during this period.

Vernacular gardens are by their nature ephemeral places, so Bayard’s photographs from the 1840s showing his own garden, clearly a place he valued, and which features repeatedly in his work, is especially captivating for anyone interested in these spaces.

A strong sense of composition is evident in ‘Self-portrait in the garden’ (1847). The photographer leans on an enormous barrel, on top of which a tall ceramic vessel is placed, creating a connection between these two bulky objects, while a simple wooden ladder, balanced against the garden wall, adds more height and balance. If we look closely at the slightly irregular grid of the rustic trellis forming a background to the photograph, stems of a climbing plant are visible, trained along its structure. At ground level we see various terracotta pots, a watering can, as well as low-growing, evergreen plants – probably box – edging the borders. As well as plants, Bayard appears to have appreciated the objects and paraphernalia of gardening.

Bayard’s interest in the natural world is clear from his earliest photographic impressions made in the 1830s using salted paper prints and cyanotypes. He takes great care in the arrangement of plant specimens, feathers, fragments of cloth and lace. A long raceme of wisteria flowers looks elegant placed next to a leaf with a similar form, while in another image Bayard uses a range of different shapes – the spiky structure of a nigella flower contrasting with the softer outlines of sweet peas and nasturtiums.

Plant specimens

Salted paper print, about 1839 – 1841

Arrangement of flowers

Salted paper print, about 1839 – 1843

Arrangement of Specimens

Cyanotype, about 1842

Three feathers

Cyanotype, 1840 – 1841

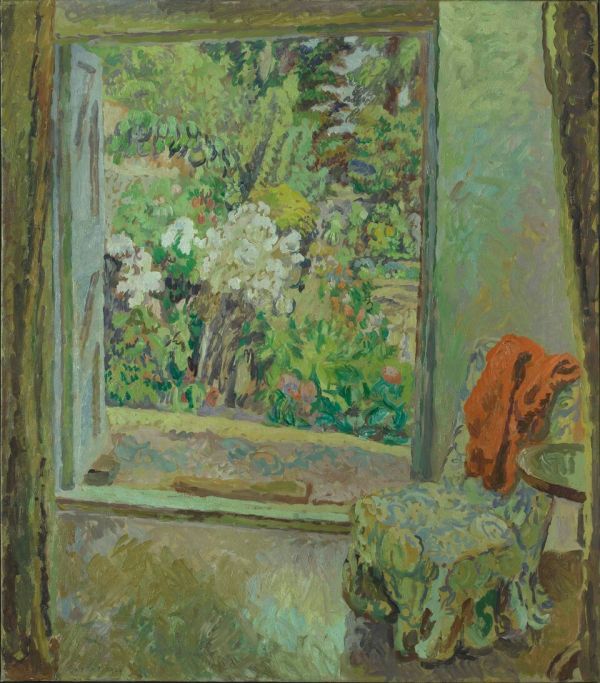

Further photographs of Bayard’s garden appear to show the trellis later in the season, clothed with vine leaves. In ‘Chair and watering can in the garden’, the vine leaves, combined with tall hollyhocks in the flower border fill the frame with foliage, while the empty chair seems to invite the viewer to take a seat and enjoy the lush growth.

Chair and watering can in a garden

Salted paper print from a calotype negative, about 1843 – 1847

Self-portrait in a garden

Salted paper print, about 1845 – 1849

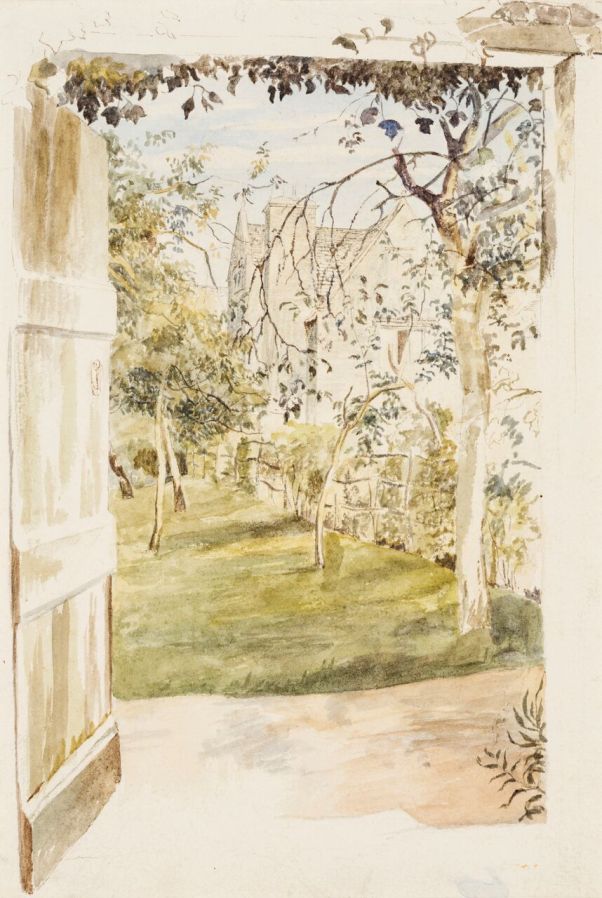

‘Garden Wall with tools’ (September 1844) suggests late summer warmth, with slanting shadows in the bright light, and an open shutter on the right, allowing sunlight into the house.

Garden Wall with tools

Salted paper print, September 1844

Leaves on a trellis

Salted paper print, about 1847

Still Life in Bayard’s Garden: Baskets, Watering Can and Planter Pots

1848

Potted Plant in a Garden

Salted paper print, 1849

The wooden gate in ‘Self-portrait in front of garden’ (1845), is another example of rustic woodwork, and features in several photographs of various visitors to Bayard’s garden.

Self-portrait in front of garden

Hand coloured salted paper print June 1845

Two Men and a Girl in a Garden

Albumenised salted paper print, about 1847

Group portrait in garden

Salted paper print, about 1847

Portrait of Georgina Benoist at gate

Salted paper print, about 1840 -1849

Bayard also produced still life studies of flower arrangements, often using dahlias. Originally from Mexico, dahlias began to be cultivated as garden plants in Europe in the 1820s. Dahlias were at the height of their popularity in the 1830s and 40s, when dozens of new double varieties were introduced by plant breeders, including a red flowered form which hadn’t been seen previously. These plants were highly collectible and still relatively expensive to buy, so represent a nod to Bayard’s engagement with gardening fashions. ‘Vase of flowers’ (about 1845 – 1846) shows dahlias in pride of place in his arrangement, with the light from a window creating a splash of brightness on a wall and the vase of flowers casting a beautiful shadow.

Vase of flowers

Salted paper print, about 1845 – 1846

Vase of flowers

Salted paper print, 1847

Flowers in a vase

Salted paper print, about 1845 – 1849

Hippolyte Bayard was employed as a civil servant in the 1830s and, according to the J Paul Getty Museum, ‘devoted much of his free time inventing processes that captured and fixed images from nature on paper using a basic camera, chemicals and light.’ However, Bayard’s achievements were overshadowed by the launch of the daguerreotype in 1839. With the backing of the French government, the daguerreotype became the first commercially successful photographic process.

Bayard’s response to his disappointment at having been overlooked in favour of Daguerre’s rival process was to produce an extraordinary photograph – ‘Self-portrait as a drowned man (1840). The text written on the back of the image reads:

‘The corpse of the gentleman you see here . . . is that of Monsieur Bayard, inventor of the process that you have just seen. . . . As far as I know this ingenious and indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with perfecting his discovery. . . . The Government, who gave much to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life! . . . He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him. Ladies and gentlemen, you’d better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay.’

Bayard’s creation of this photographic alter ego, expressing both his personal pain and his unfair treatment by the French government, is full of satirical complexity. Today the image seems extraordinarily modern, bringing to mind the work of artists like Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, and many others, who have used photographic self-portraits in their work.

The powerful message of Bayard’s self-portrait seems to have prompted the French Academy of Sciences to recognise and acquire details of his photographic process and Bayard used the money to purchase better equipment to progress his experimentation. His involvement with photography continued – as well as being a founder member of the Société française de photographie he was also commissioned to record historical sites in France for the Historic Monuments Commission.

Self-portrait as a drowned man 1840

(Wikimedia Commons)

In the studio of Bayard

Salted paper print from a paper negative, about 1845

Links to Bayard’s work at the J Paul Getty Museum below:

Further reading:

J Paul Getty Museum biography of Hippolyte Bayard here

Hippolyte Bayard on Wikipedia here

Curator Carolyn Peter’s reflections on Bayard here

The Stanford Dahlia project here