Bringing Home Christmas from The Book of Christmas by Thomas Kibble Hervey. First published in 1836, this 1888 version is made available by the University of California Libraries via archive.org

Our understanding of Christmas and New Year celebrations in late Georgian England (and earlier) owes an enormous debt to The Book of Christmas by Thomas Kibble Hervey (1799 – 1859). Published in 1836 Hervey’s survey of the festive season examines in detail everything from the food people ate and the carols they sang, to a multitude of annual local events.

Bringing evergreen branches inside to decorate our houses in wintertime is still a much loved tradition. Hervey allocates several pages of his book to these decorations and their importance in seasonal celebrations:

‘One of the most striking signs of the season, and which meets the eye in all directions, is that which arises out of the ancient and still familiar practice of adorning our houses and churches with evergreens during the continuance of this festival.’

The origins of this ancient custom and its symbolism of renewal are rooted in European folklore, and over time evergreen decorations became incorporated into Christian festivals. The Puritans briefly rejected these decorations in churches owing to their heathen origins, but Hervey observes that the practice, despite ‘outcry and prohibition’, had once again become as popular as ever.

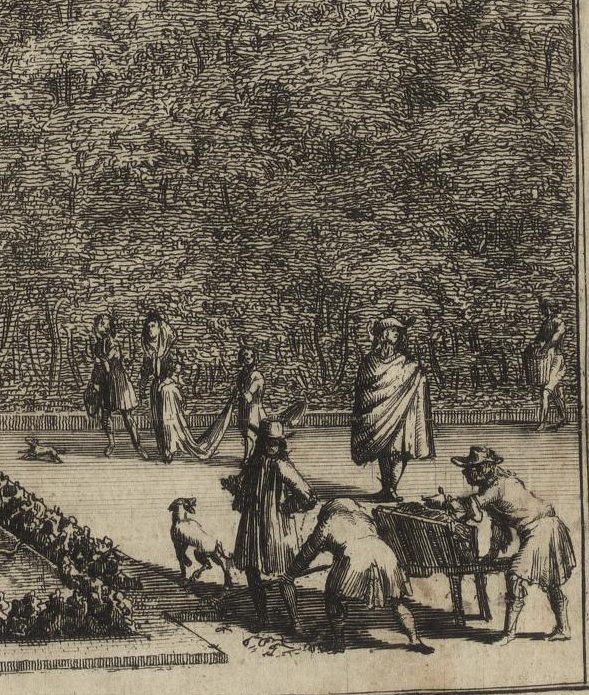

The illustration for this section of the book shows a country man on his way to market with a cartload of evergreens. These, according to Hervey, would be used to decorate mantel-pieces and windows, and wreaths would be made for lamps, Christmas candles and for use as table decorations. He also mentions displays of greenery in markets and shops, observing that, ‘every tub of butter has a sprig of rosemary in its breast.’

Material was gathered both from hedges and ‘winter gardens’ and could include holly, rosemary, bay, mistletoe and ivy – but was not restricted to these plants. Yew and cypress are mentioned as well as box, pine, fir and even myrtle where it was available.

A fourteenth century song he describes is interesting for mentioning holly and ivy as Christmas decoration. The song confirms the precedence of the holly, which is brought inside while ivy is confined to outdoor use:

‘Nay Ivy! Nay it shall not be, I wys;

Let Holy have the maystry, as the manner ys.

Holy stond in the halle, fayre to behold;

Ivy stond without the doore: she is full sore a cold.’

Written before the Christmas tree became popular in England, Hervey relates a popular custom from Germany and Sicily in which

‘.. a large bough is set up in the principal room, the smaller branches of which are hung with little presents suitable to the different members of the household.’

The British Library cites the popularity of his book as a factor in the revival of Christmas celebrations in the 1840s and their continuation through the Victorian period. Robert Seymour’s accompanying illustrations are a fascinating record of home and street life in the mid 1830s. Hervey’s enthusiasm for the festive season is infectious – even if Christmas is not your favourite time of year, I do recommend a dip into this book – links below.

The Book of Christmas features illustrations by Robert Seymour

Robert Seymour records in minute detail the decorations at either end of a gun displayed above the kitchen mantelpiece, .

Evergreen sprigs decorate the mirror and light fitting in this drawing room.

This grandfather clock has been decorated for New Year celebrations.

Further reading:

The Book of Christmas (1836) The British Library publishes some illustrations from the original version of the book – plus links to other Christmas related publications.

Thomas Kibble Hervey Wikipedia entry

Robert Seymour Wikipedia entry