William Forsyth (1737 – 1804) stipple engraving by Samuel Freeman (Wellcome Institute Collection)

When William Forsyth published his Treatise on the culture and management of fruit trees in 1802 he had been gardener to King George III for eighteen years, during which time he was credited with the transformation of the royal orchards at Kensington Palace. His experimental pruning techniques rejuvenated the Palace’s old fruit trees making them productive once more. Forsyth was also celebrated for his invention of a dressing for damaged trees, which was believed to assist in restoring them to good health.

Before his royal appointment, William Forsyth already had a prestigious career in horticulture. Born in Aberdeenshire, Forsyth re-located to London to train at the Chelsea Physic Garden under another Scottish gardener, Philip Miller (1691 – 1777), eventually becoming head gardener there in 1771. He took up the position of superintendent of the royal gardens at Kensington Palace and St James’s Palace in 1784. The now familiar garden shrub forsythia was named for him and he is an ancestor of the late entertainer, Bruce Forsyth.

William Forsyth’s employment brought him to the attention of the English establishment, who saw his work in the royal gardens. They were impressed by his success with the King’s fruit trees, and persuaded by the efficacy of his ‘composition’ or remedy for damaged trees. Against the background of the Napoleonic Wars when access to good timber was essential, the composition was discussed in both houses of Parliament and the recipe published in the national interest. It was printed in local newspapers across the country to encourage landowners across England to adopt it for the health of their forest trees.

This dressing, or ‘composition’ as Forsyth called it, was made out of cow dung, lime plaster (‘that from the ceilings of rooms is preferable’), wood ashes and sand. It was applied to tree wounds after careful preparation of the surface, first removing any dead or diseased wood. Gradually, the damaged area was restored and covered over by new bark.

In his book, Forsyth explains how his work with trees started. As the new gardener to the royal family in 1784, Forsyth was expected to produce abundant and tasty fruits for the royal tables, but when he arrived at Kensington Palace he was faced with a dilemma.

The gardens contained dozens of fruit trees, some large orchard trees, dwarf standard trees, and others wall trained, but the trees were old and had stopped bearing well. He observes the pear trees are ‘in a very cankery and unfruitful state’, but after changing the soil around the trees and pruning them, 18 months later he notices no improvement. Forsyth says,

‘I began to consider what was best to be done with so many old pear-trees that were worn out. The fruit that they produced I could not send to his Majesty’s table with any credit to myself, it being small, hard and kernelly.’

But rather than grub up the old trees and wait for new stock to start bearing – Forsyth estimates this would have taken ‘between twelve and fourteen years’ – he decides to ‘try an experiment, with a view of recovering the old ones.’

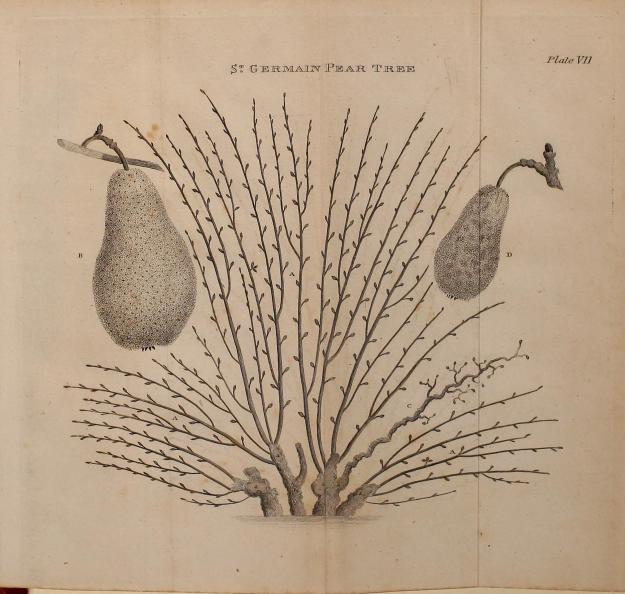

In 1786 Forsyth began a process of ‘heading down’ seven old trees, probably best explained by the illustrations below. Some large branches were removed as close to a bud as possible, allowing the tree to produce new, vigorous shoots. In the case of wall trained pear trees, the new growth was carefully tied in.

St Germain Pear Tree

This plate represents an old decayed Pear-tree, with four stems, which was headed down, all but the branch C, and the young wood trained in the common way, or fan-fashioned.

Branches marked A show young wood, producing the fine large fruit B.

C. An old branch pruned in the common way, having large spurs standing out a foot or eighteen inches, and producing the diminutive, kernelly and ill-favoured fruit D, not fit to be eaten.

White Beurre Pear Tree

Fig. 1. An old decayed Beurre pear-tree, headed down at f, and restored from one inch and a half of live bark.

Fig. 2. An old branch of the same tree before it was headed down, trained and pruned in the old way, with spurs standing out a foot, or a foot and a half from the wall; and the rough bark, infested with a destructive insect

The diagram of an old White Beurre pear tree shows detail of an old branch which has been removed – the bark was infested with insects, so the pruning has the effect of eliminating persistent pests as well as promoting new growth.

As well as the headed down trees, Forsyth kept seven trees as a control group and pruned these in the regular way. Forsyth observes that in the third year after ‘heading down’, the trees were producing more fruit that they did previously, and that it is larger and of better quality. After four years the trees are producing ‘upwards of five times the quantity of fruit that the others did’. Here’s an excerpt showing the improved yield and also the systematic nature of Forsyth’s records.

Trees treated according to the common method of pruning:

‘A Crasane produced one hundred pears, and the tree spread fourteen yards.

Another Crasane produced sixteen pears, and the tree spread ten yards.’

Trees headed down and pruned according to my method:

‘A Crasane bore five hundred and twenty pears.

A Brown Beurre bore five hundred and three pears.

Another Brown Beurre bore five hundred and fifty pears.’

Forsyth’s crops were even greater using his pruning method on smaller, standard trees; so much so, he ‘is obliged to prop the branches, to prevent their being broken down by the weight of it.’

In other chapters, Forsyth records similar successes with apples, plums, apricots, peaches and grape vines, and towards the end of the book publishes a series of endorsements from prominent people who have tried his pruning methods and his composition in their own gardens.

What’s inspiring today about Forsyth’s treatise is his willingness to use his vast horticultural experience pragmatically – and creatively – to address a problem. He teaches us that from time to time it’s worthwhile to step back from the ‘correct way’ of doing things and experiment with a different approach to address the challenges that gardening presents us with.

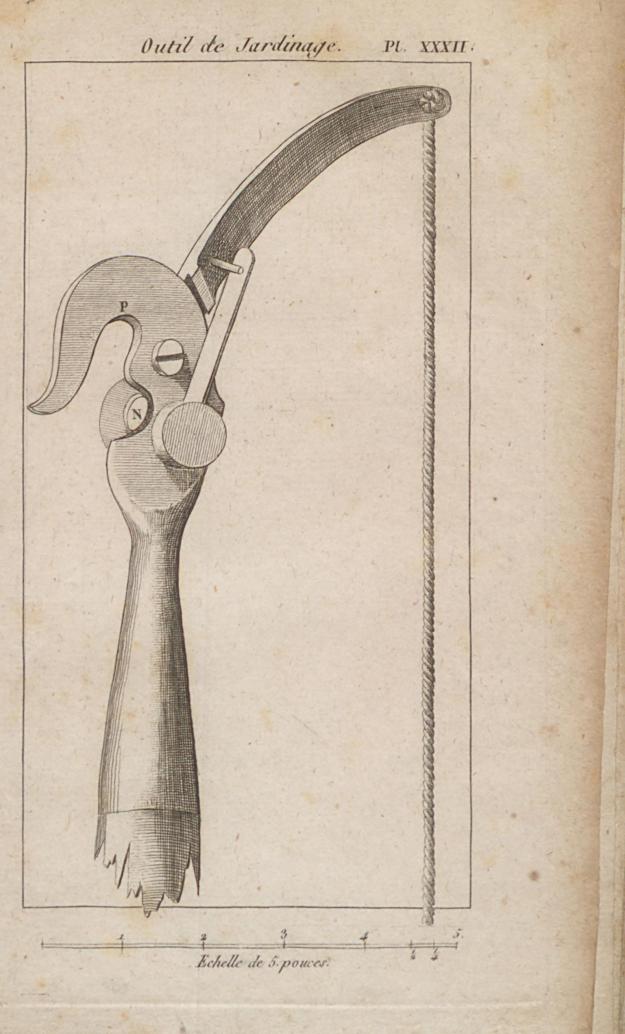

Links below to Forsyth’s Treatise. I’ve included a plate of the pruning tools used by Forsyth and an explanation of these from the text.

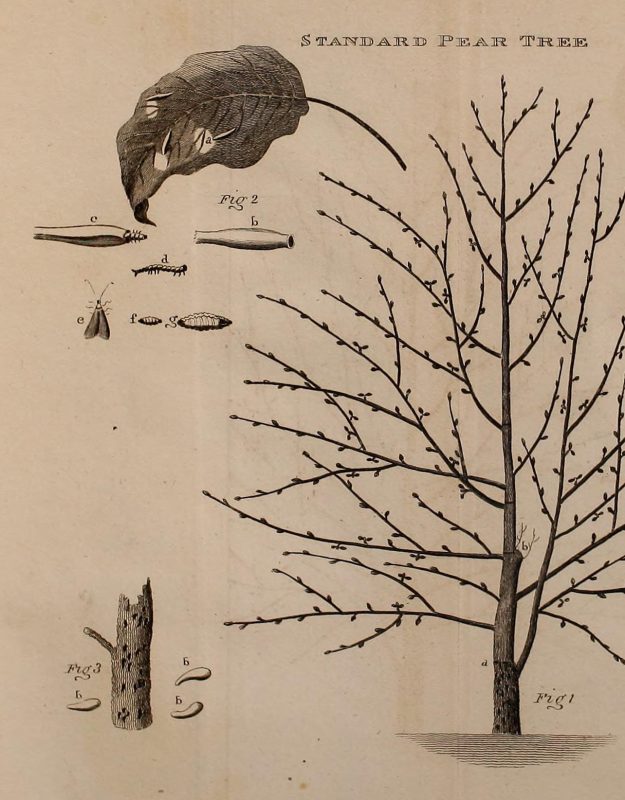

Standard Pear Tree

An old Bergamot Pear, headed down at the cicatrix a, taken from the wall and planted out as a dwarf standard.

b. A wound, covered with the composition, where a large upright shoot was cut off, to give the leading shoot freedom to grow straight.

Figs 2 and 3 show the insect (probably the Codling moth) so destructive to fruit trees.

Tools used by Forsyth both for pruning and for preparing wood to receive his healing composition

Forsyth’s directions for making his Composition from 1791

Gardener with pear tree, Ote Hall, Sussex. Photographed by Charles Jones circa 1901 – 20 (V&A Collections)

The above photograph gives a sense of the abundance of a wall trained pear, when pruned skillfully.

Further reading:

William Forsyth’s Treatise on the culture and management of fruit trees