One of a pair of garden lodges at the original entrance to Montacute House, Somerset with yew hedging and topiary in the foreground.

Yew in all its various forms underpins the planting of the garden at Montacute House, in Somerset. Twin rows of yew topiary line the drive to the Grade 1 listed house, while hedges of various styles and heights divide spaces and define paths and walkways. Constructed out of local Ham Hill stone, with its deep, golden hue, Montacute House was built in the late 16th century by Sir Edward Phelips, and passed into National Trust ownership in 1927.

Under the direction of head gardener Chris Gaskin, much of Montacute’s yew is being re-shaped, bringing the plants back to a more manageable size and to a scale that is in harmony with the house and its surroundings. This has involved some drastic pruning, reducing their height and spread and thinning the centre of the plants to bring in light and air. Fortunately, yews respond remarkably well to this treatment, having the ability to re-generate from old wood, and are already showing fresh green growth on the cut branches.

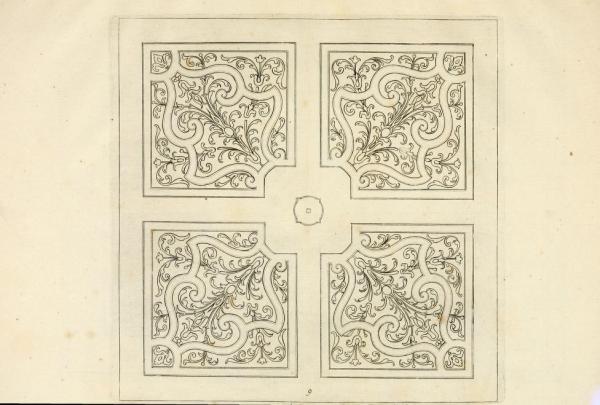

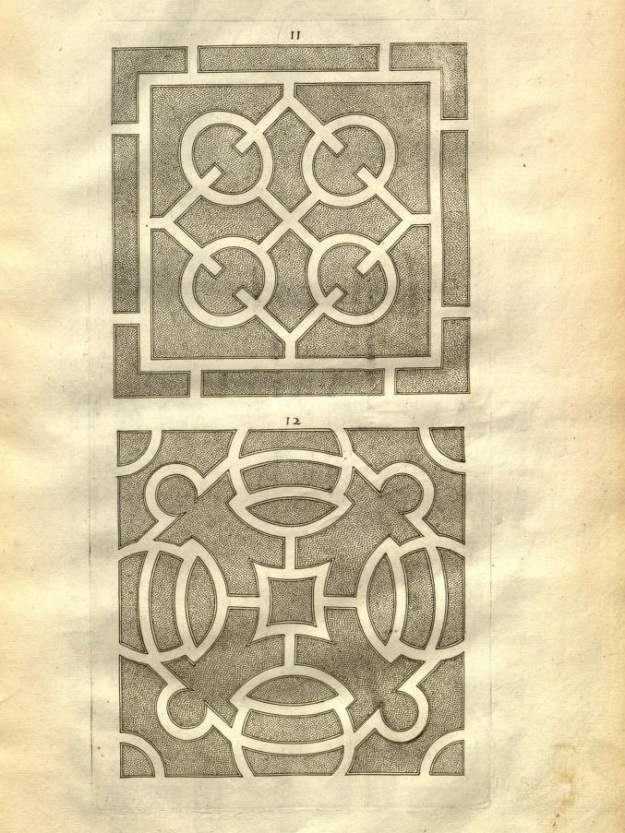

The re-instatement of the parterre garden is also part of the plan for re-modelling the garden. Situated on the north side of the house, this large rectangular area of lawn is sunken, with a fountain at its centre. Stone steps on each side lead up to a surrounding walkway, providing views of the parterre and the parkland beyond.

The first step in this enormous task has been for the gardeners mark out the shape of the parterre, which they’ve done by mowing paths in the lawn. These pathways will eventually be covered with gravel and the beds planted with flowers. It’s expected this project will take ten years to realise – perhaps longer – as the effect of Covid-19 on the National Trust’s funding situation continues to be felt.

Towards the end of the afternoon when most of the visitors had gone home, we had the opportunity to ask two of the staff about their experience of Montacute in lockdown. With no visitors and hardly anyone at the house, weeds started to grow up through the paving. Without their foliage, the newly pruned yew trees looked like wooden torches and the faint outline of the parterre in the grass contributed a haunting feel to the garden. With a bit of imagination, it felt like an abandoned place, in the process of being reclaimed by nature and pulled back into wilderness.

Although the people have now returned, this feeling has not completely disappeared – the un-mown parterre beds were full of wildflowers growing through the grass and children running along the grass pathways were delighted by the challenge of following their geometric shapes.

The lawn in front of the original entrance to the house is flanked by long flower borders and the view over the estate is framed by two matching garden lodges. Now a tranquil space, this area would once have been a bustling courtyard, with estate traffic and guests coming and going. It’s a reminder of how plants can create a special atmosphere – sometimes an impression of permanence and sometimes a sense of order slipping away.

More about the history of the house and gardens in the link below:

The row of yews lining the drive to the 18th century entrance before pruning. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A line of yew trees being re-shaped. The encroaching trees behind the yews have caused them to lean towards the light and grow out of shape.

A line of yew trees being re-shaped. The encroaching trees behind the yews cause them to lean towards the light and grow out of shape.

new growth appearing on the pruned trees.

Cloud-pruned yew hedge.

The parterre garden at Montacute before restoration work. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The parterre garden

The shape of the parterre, based on a 19th century design, has been laid out by mowing pathways through the lawn.

Some of the yews are quite characterful – these look as though they are about to make off into the parkland together.

Lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum) in flower in the unmown sections of the parterre.

Steps down to the sunken parterre garden.

Rear elevation of Montacute House. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A pair of lions with human faces hold the crest above the original front door to Montacute House.

Most of the roses had finished when we visited.

Visitors (with deep pockets) can stay in this exquisite gatehouse building at the Montacute estate, managed by the National Trust. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Further reading: