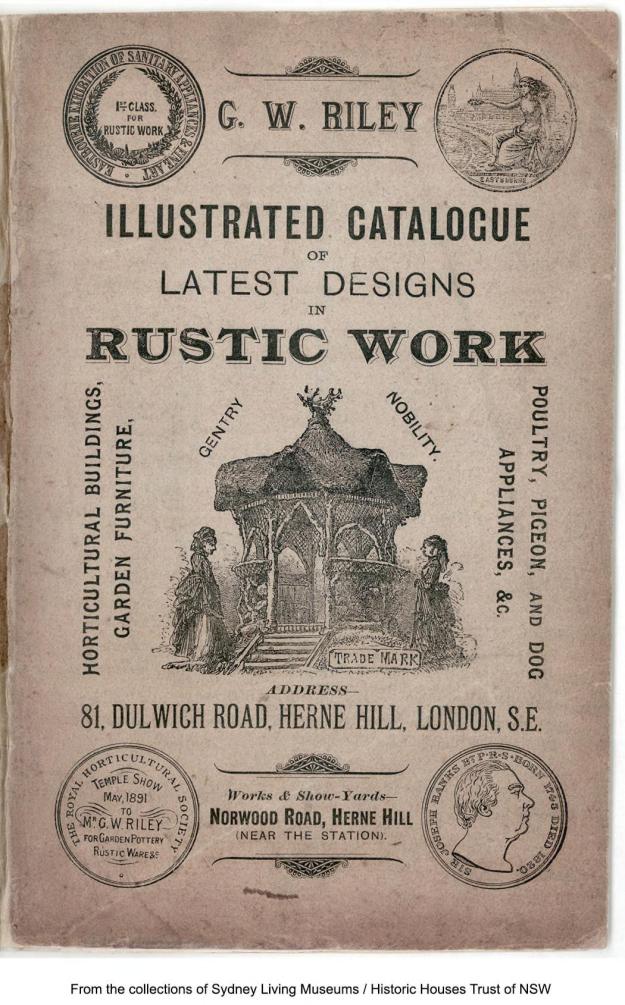

G W Riley’s Illustrated Catalogue of designs in Rustic Work from 1895 reveals an astonishing array of garden buildings, furniture and accessories, all constructed out of wood in rustic style. Based in Herne Hill, a relatively new south London suburb in the 1890s, his workshops and show yards were in Norwood Road, near to the station, enabling potential customers to visit before making a purchase, and for the goods to be despatched by rail to a station close to their homes.

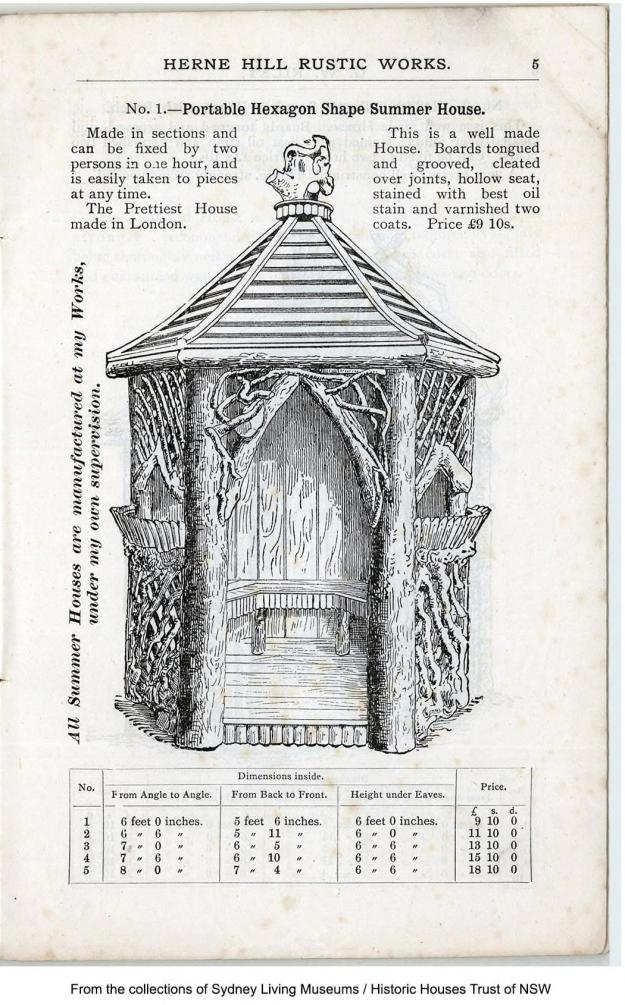

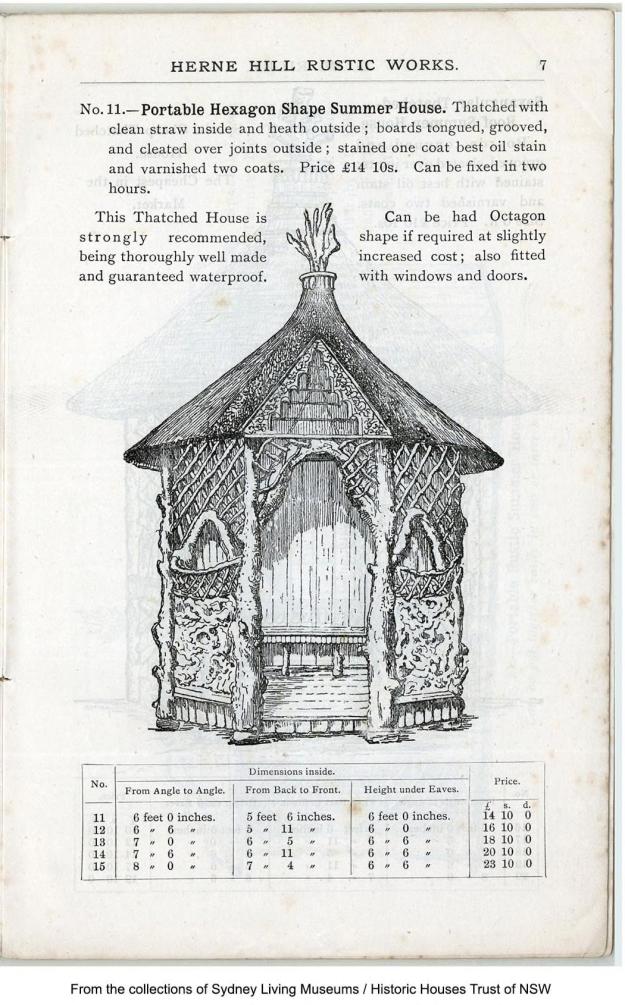

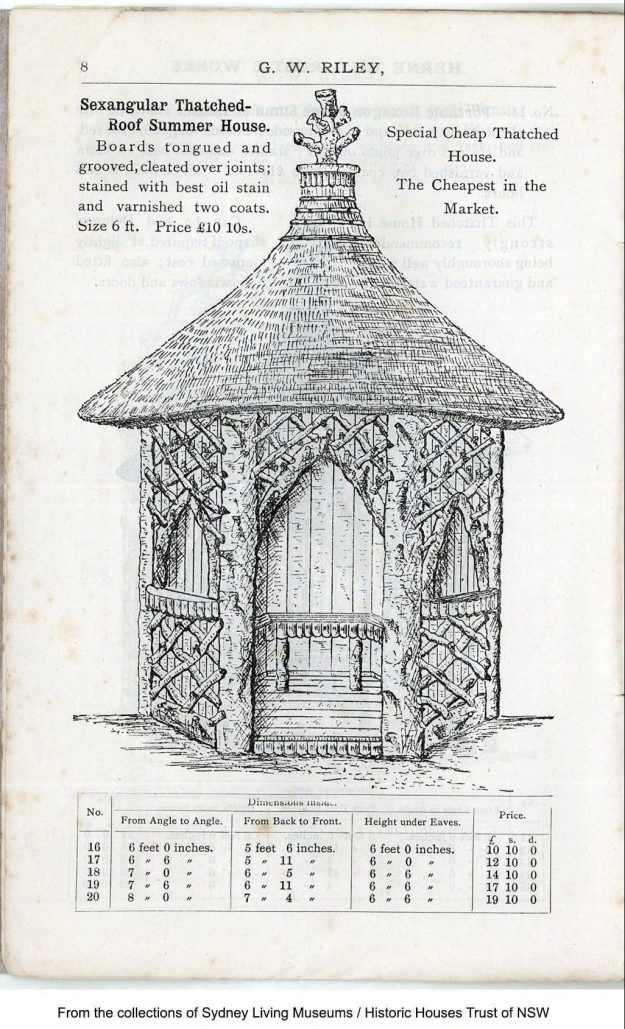

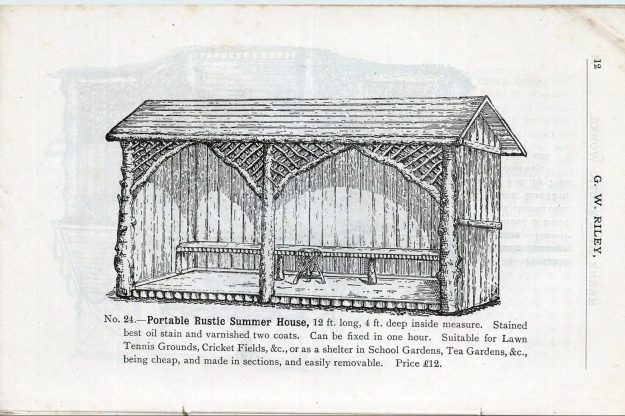

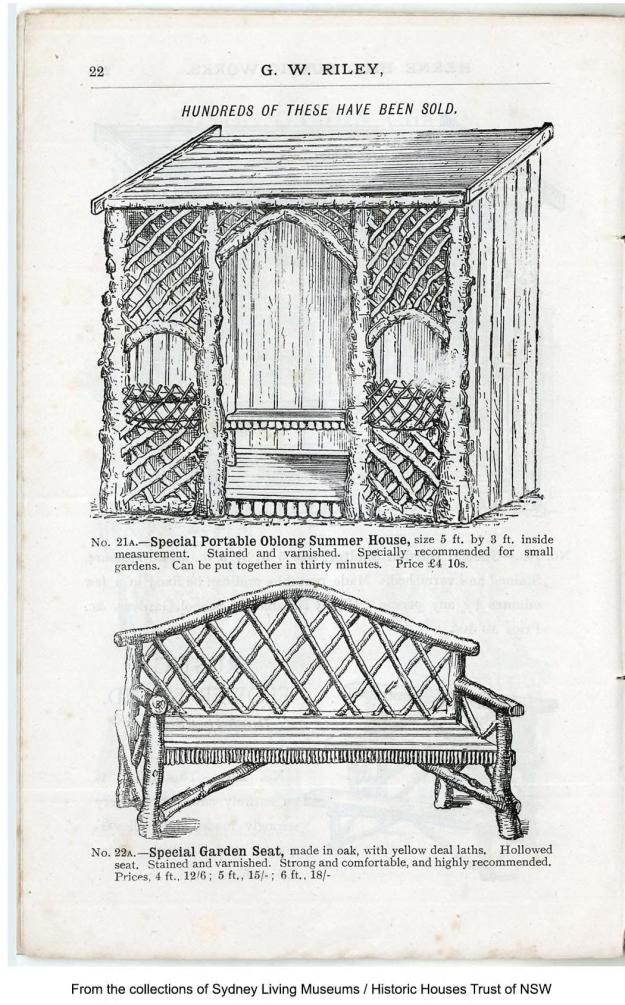

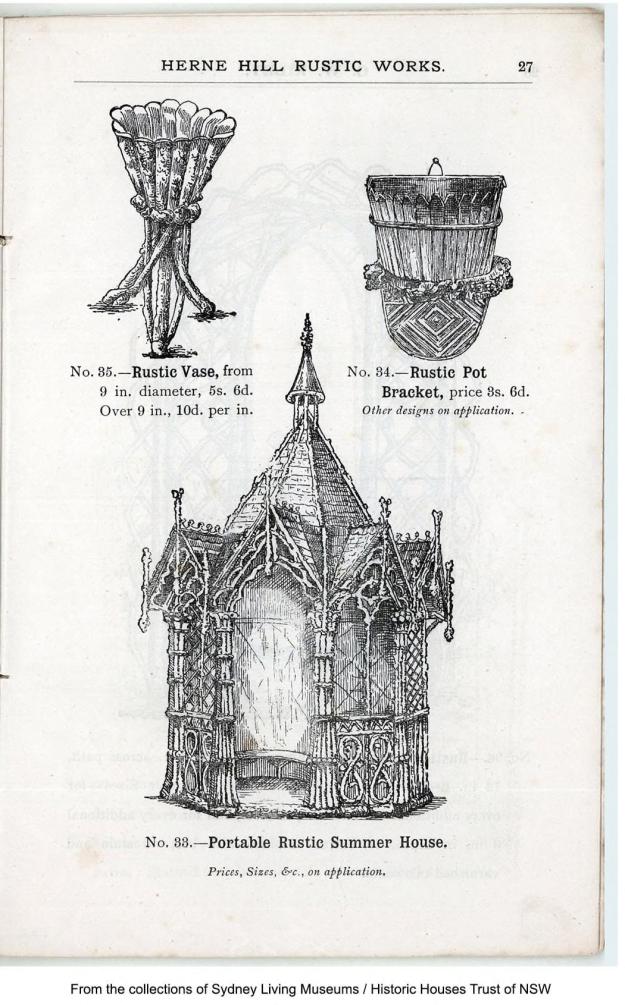

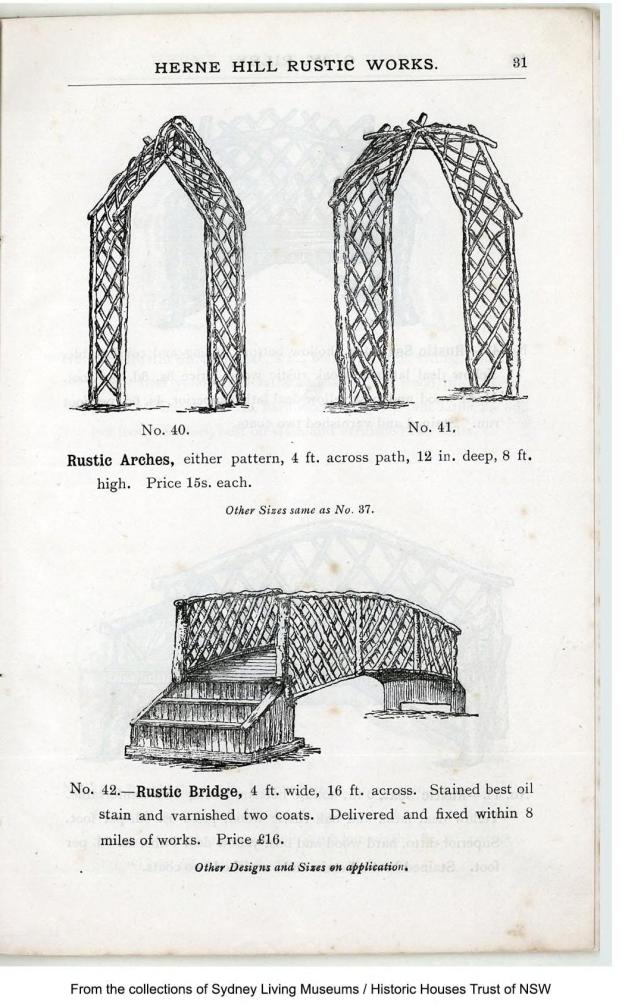

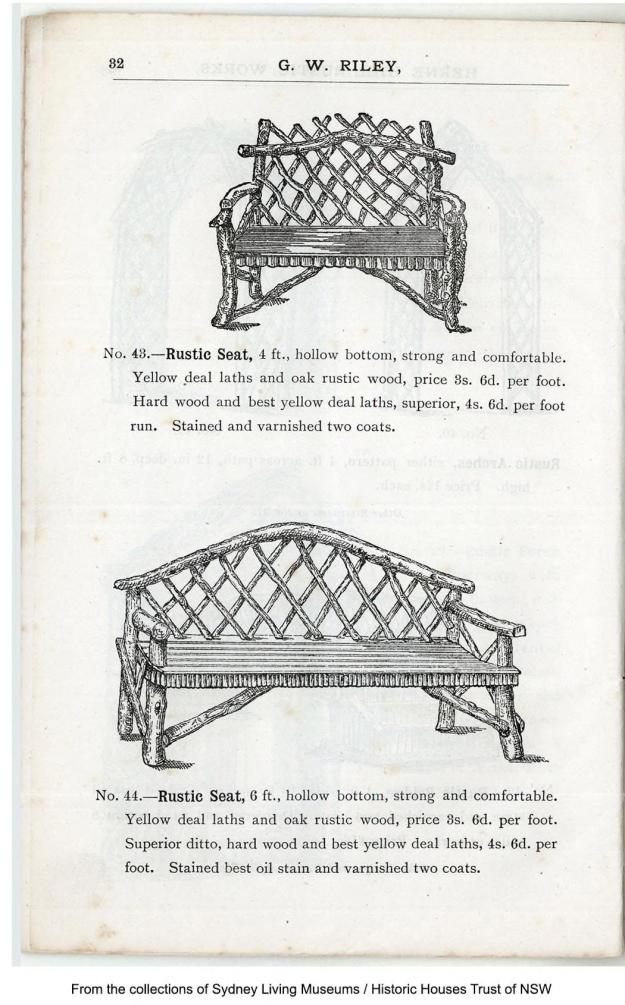

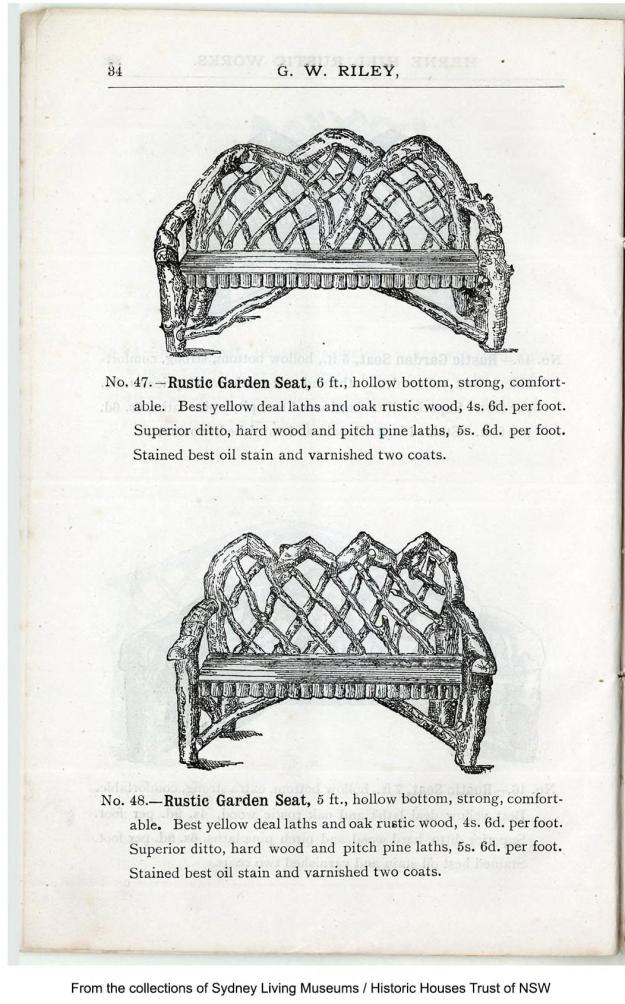

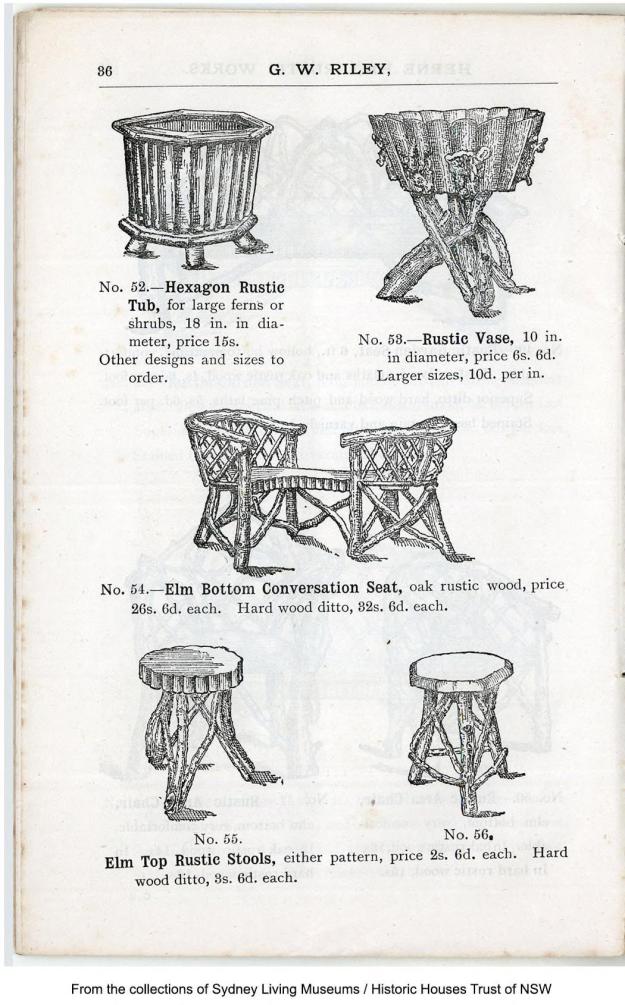

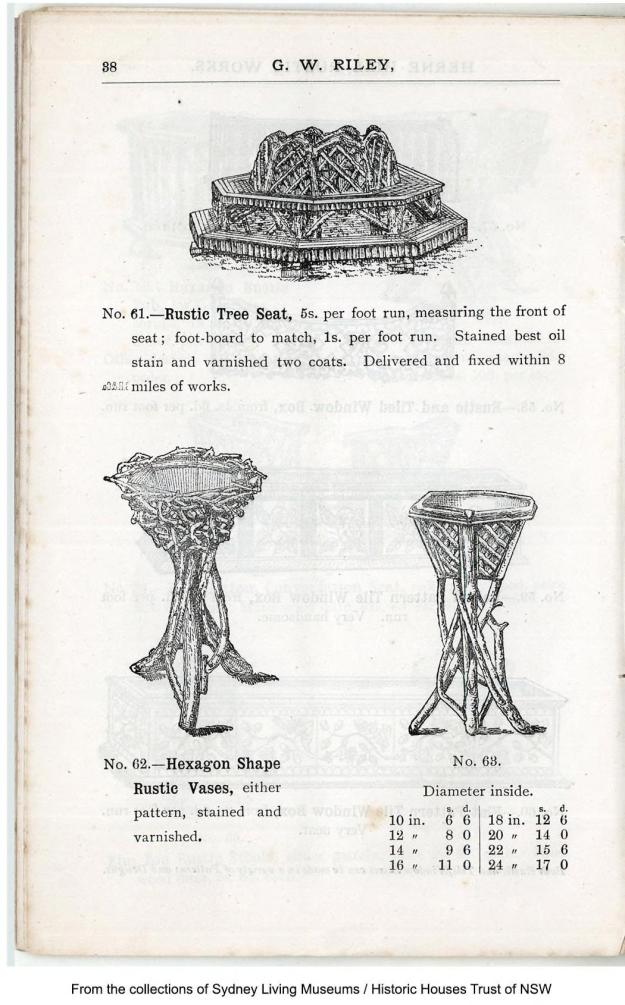

Riley’s summer houses were made to order and took around two weeks to complete. Each design came in a range of sizes, some intended purely for domestic use, while larger structures are described as ‘suitable for Lawn Tennis grounds, Cricket fields &c or as a shelter in School Gardens, Tea Gardens &c.’ As well as garden buildings, Riley made and sold rustic themed seats, window boxes and arches for climbing plants. A particular favourite of mine is a rustic porch designed to adorn a front doorway – thereby transforming a suburban house into something more like a country cottage.

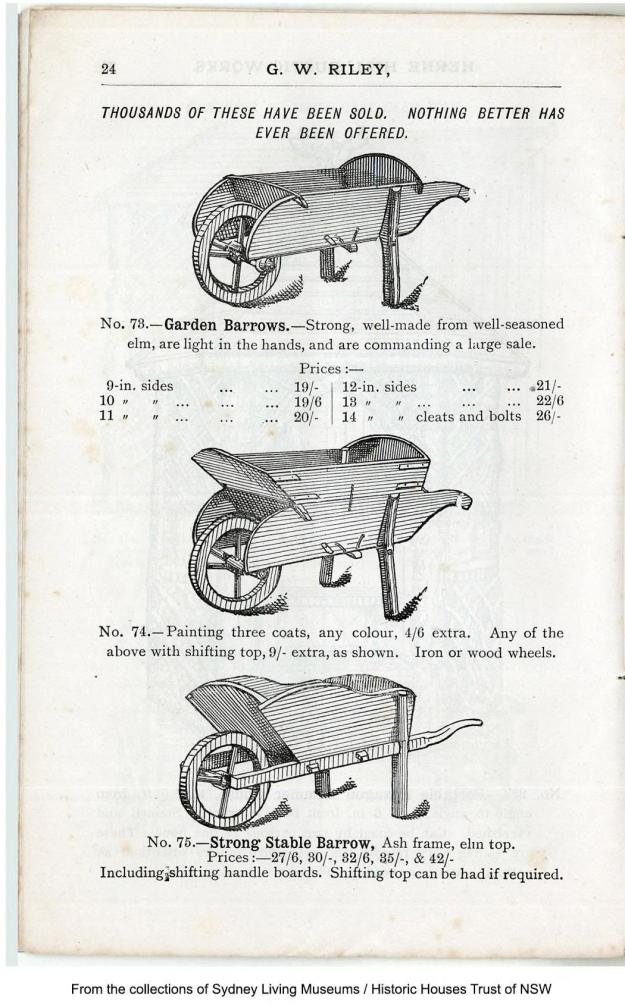

As well as the extensive range of rustic works, Riley also sold dog kennels, pigeon and poultry houses, wheelbarrows and lawnmowers. His catalogue boasts medals for rustic work, including one from the Royal Horticultural Society in the category of Garden Pottery and Rustic Wares.

The inspiration for rustic style has its origins in the Romantic Movement and the English landscape gardens of the 18th century. ‘Grotesque architecture, or, Rural amusement:’ first published in 1767, provides an illustrated survey of fashionable garden buildings, including huts, retreats, summer and winter hermitages, and grottos, suggesting these ‘may be executed with flints, irregular stones, rude branches, and roots of trees’.

Rustic style continued its popularity in 19th century gardens, particularly towards the end of the Victorian period. The rustic aesthetic embraced the natural shapes of unfinished wood, making these irregular forms a feature of the designs. According to the Smithsonian Museum, ‘Rustic furnishings and accessories were thought to be especially suited to the garden, as they blended in with the natural landscapes.’

Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (1856) by the influential garden writer and journalist Shirley Hibberd (1825 – 1890) reflects an ongoing enthusiasm for all things rustic in the mid 19th century, especially amongst Hibberd’s target audience, the emergent urban middle classes.

The summer house was a rustic adornment Hibberd was especially fond of, devoting a whole chapter to them, and describing these structures as ‘desirable, and indeed almost necessary features in gardens of all dimensions and styles.’ Hibberd reveals that this was his preferred place to write, as long as the weather permitted.

A bit like today’s flat pack furniture, Riley’s summer houses were constructed out of wood in sections, and delivered to customers’ homes to be assembled themselves or with the help of a handyman. Riley’s catalogue advertises some of the summer houses as being ‘portable’ and Hibberd sheds some light on why this might have been a desirable feature for some customers.

Hibberd, who was based in London, points out that a significant proportion of people rented their properties, and that additions tenants made to the garden, such as a summer house, could end up belonging to their landlord. However, a portable structure was classed as a ‘tenant’s fixture’ that the tenant would be able to take with them when they moved on. Hibberd mentions that some manufacturers (like Riley) had made this kind of summer house a speciality. Hibbert observes:

‘Too many of us, alas, cannot afford, except on our own freehold, to spend a large sum of money on the erection of a summer-house, and then on the expiration of a tenancy to have to leave it behind. It is clear, therefore, that we want something of a more portable nature, something, in fact, that will answer the purpose of the expensive permanent summer-house and yet remain the property of the tenant. Happily we have long been able to gratify this wish, for several manufacturers of repute have made the tenant’s fixture or portable summer-houses a speciality. Those, therefore, who have a few pounds only to spend on the luxury of a summer-house can easily obtain what they require ready made and quite complete for placing in any position in the garden.’

To modern taste, Riley’s rustic work can appear ersatz; a suburban version of rusticity. It’s easy to be dismissive of these late 19th century designs, but taste is highly subjective, and as a city dweller myself, their appeal is understandable. As towns and cities expanded in the 19th century, becoming industrial centres, city dwellers would have welcomed reminders of nature and the countryside in their gardens, even if they were inauthentic.

Because Riley’s rustic work was made largely out of unfinished wood, and destined to be placed outside in all kinds of weather, it would seem unlikely that any examples have survived. However, the Folly Flaneuse, a fellow blogger, has found remarkable examples of garden buildings in a similar style by makers Henry and Julius Caesar, Rustic House Builders from Knutsford, in Cheshire, which are still standing. So, perhaps some of Riley’s rustic work is out there, waiting to be discovered.

Links to this and other sources below:

Portable Hexagon Shape Summer House

Hexagon Rustic Summer House with Porch

Portable Hexagon Shape Summer House

Sexangular Thatched Roof Summer House

Special Cheap House

Portable Rustic Summer House

Portable Rustic Summer House

Portable Rustic Summer House

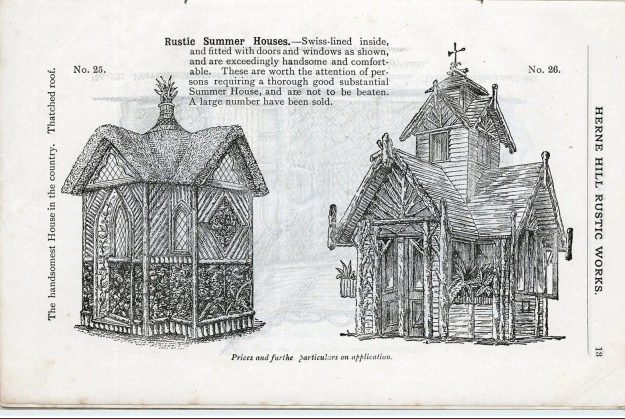

Rustic Summer Houses

Portable Rustic Summer House

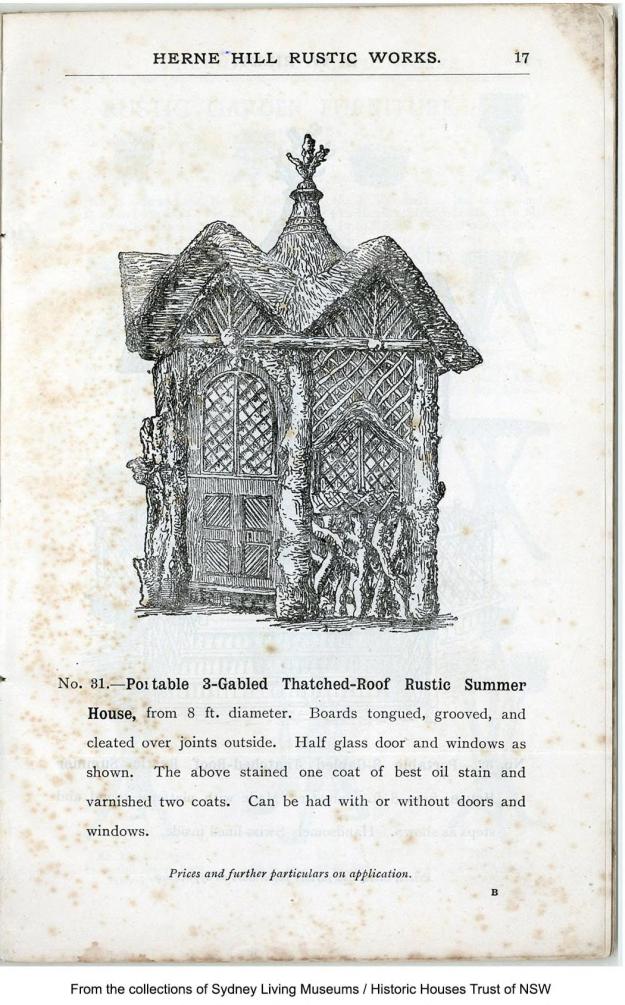

Portable 3-Gabled Thatched Roof Rustic Summer House

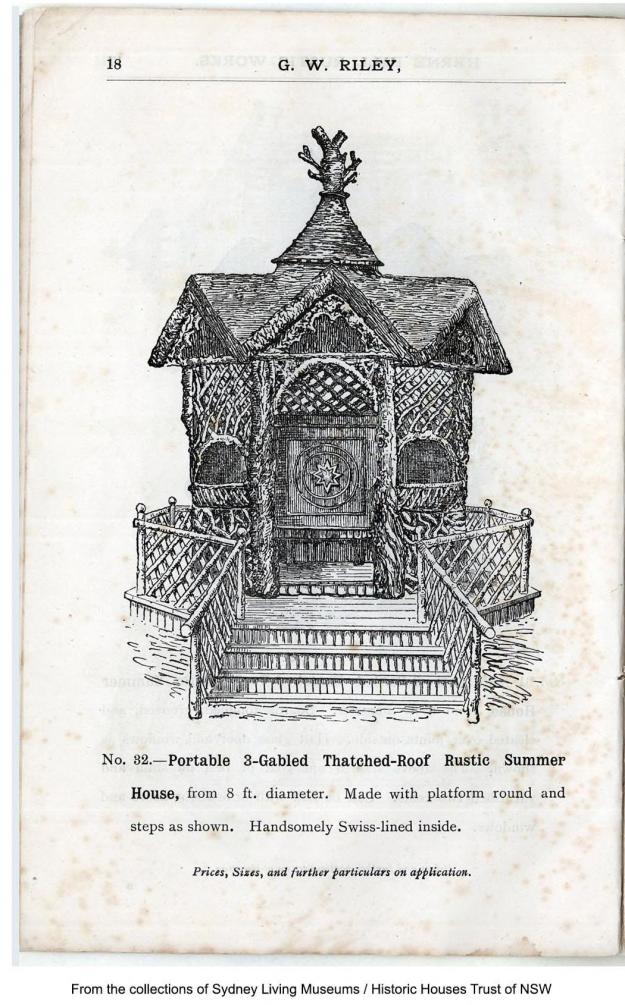

Portable 3-Gabled Thatched Roof Rustic Summer House

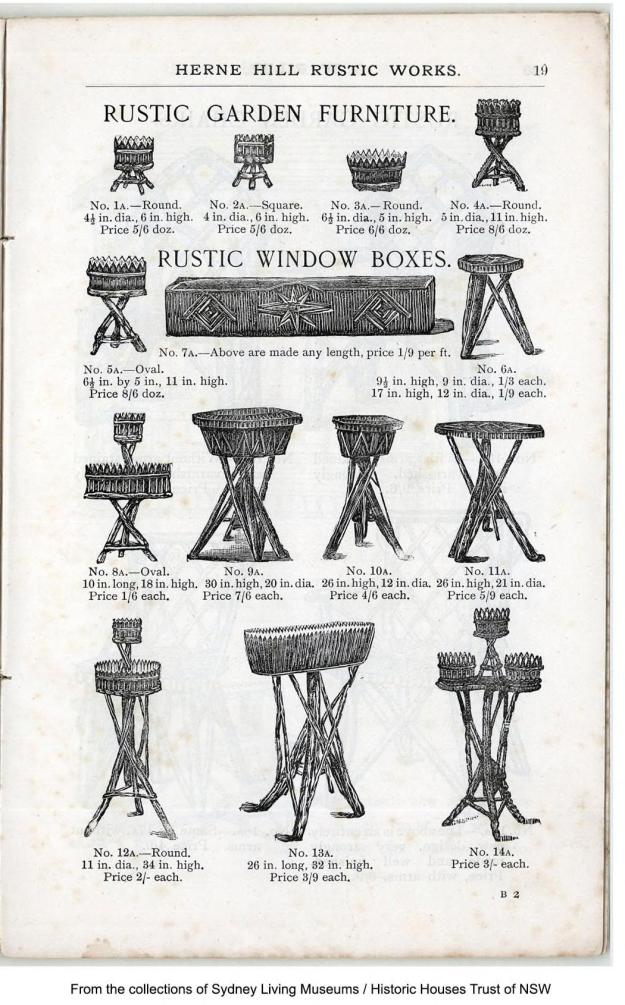

Rustic Garden Chairs

Further reading:

G. W. Riley: Illustrated catalogue of latest designs in rustic work here

Grotesque architecture, or, Rural amusement here

Smithsonian Gardens here

Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (1895) here

The Folly Flaneuse: Henry and Julius Caesar, Rustic House Builders here