Dahlia Picta Perfecta

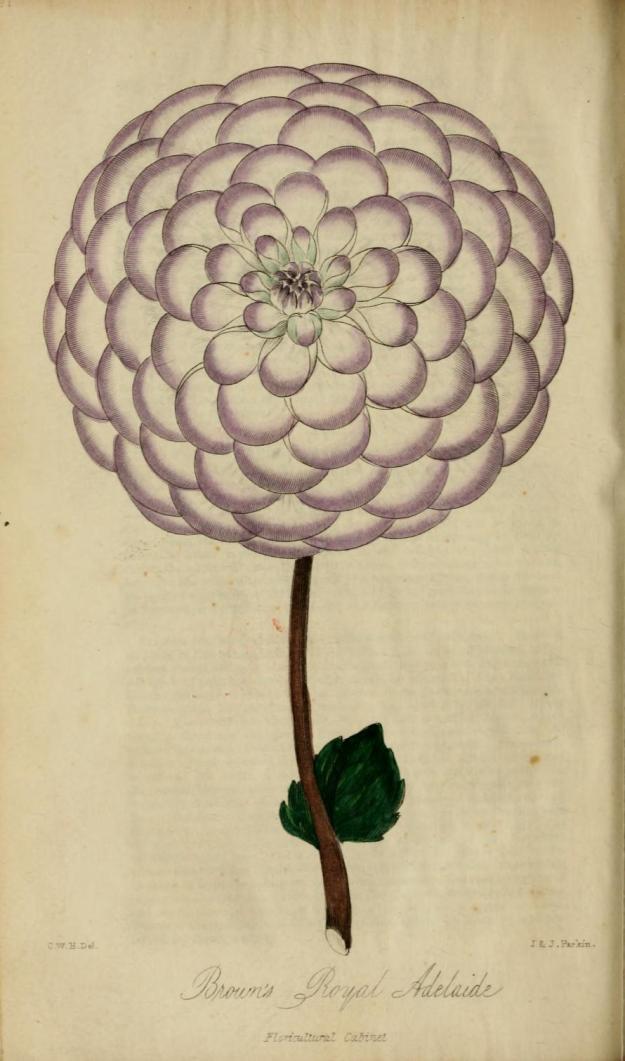

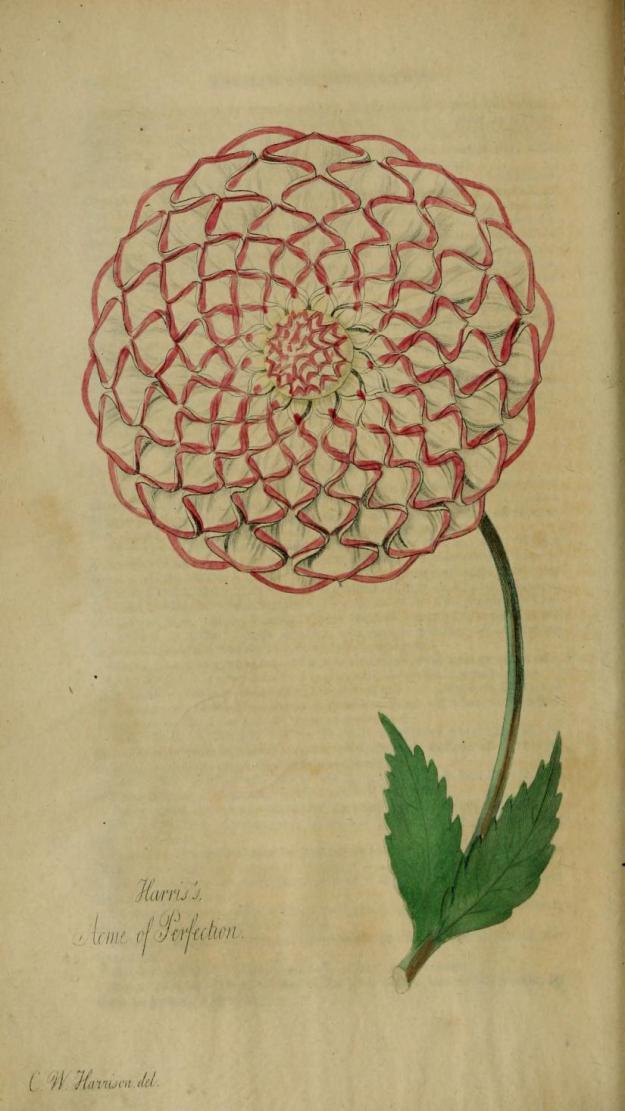

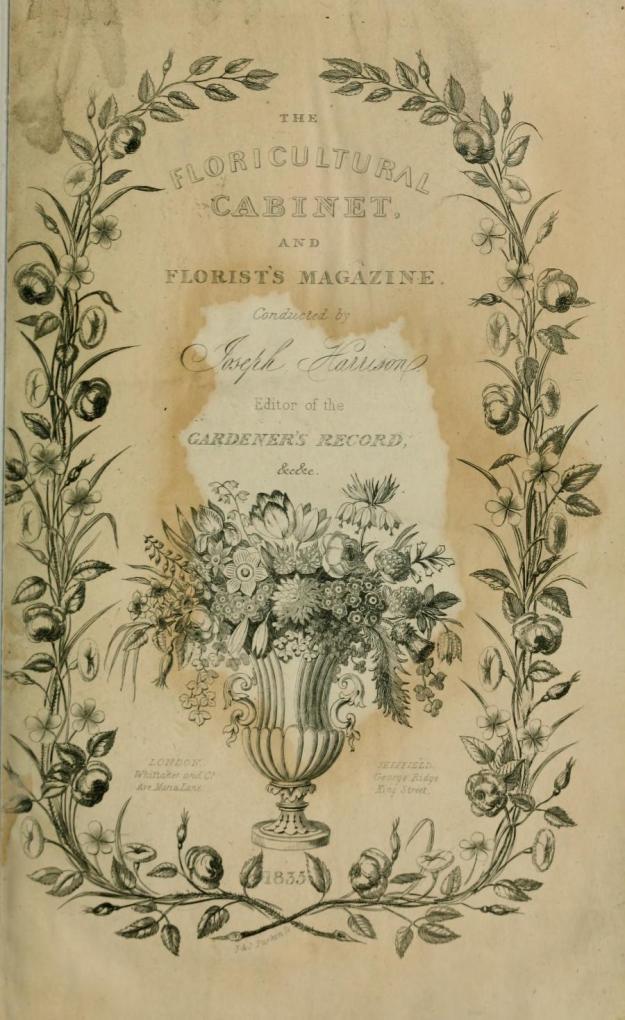

The Floricultural Cabinet 1835 (Natural History Museum)

This coloured plate showing a bright crimson ‘Picta Perfecta’ dahlia, with its beautifully shaped petals edged in black, was first published in The Floricultural Cabinet and Florist’s Magazine in 1835. Launched in 1833 by Joseph Harrison, a gardener and florist, his magazine reflects the appetite amongst amateur and professional gardeners alike for the cultivation of dahlias for show.

In the 1830s, dahlias were enormously popular garden and exhibition flowers, loved for their jewel colours, abundance of blooms and long flowering season. Starting in July, dahlia shows took place at regular intervals through the summer and early autumn. Harrison visited floral exhibitions all over the country, many hosted by newly formed horticultural societies, and published his accounts of these in the magazine.

Today his accounts give us valuable insights into the character and atmosphere of these shows. Dahlia shows ranged from those staged in public houses, such as the Baker’s Arms in Hackney Road, East London, and the Bull and Mouth Inn in Sheffield, to large exhibitions attracting huge crowds, such as the Metropolitan Society’s Grand Dahlia Show at Vauxhall Gardens in London. Many of the shows hosted dinners for members after the prizes had been given out, and some enjoyed dancing, and music from brass bands. Whatever their size, all the shows were united by appreciation for the dahlia and the spirit of competition.

Harrison’s attendance at these shows allowed him to meet the horticulturalists producing new dahlias, giving him an important overview of dahlia cultivation in England and contacts in the wider horticultural industry. He soon established himself as an influential voice informing taste and trends in gardening through his magazine, in much the same way horticultural journalists and garden designers do today.

With a format that gave advice on growing techniques from expert growers and seed and bulb suppliers, the magazine also encouraged amateurs to write in with questions and their own gardening tips. The Floricultural Cabinet was an instant success, boasting sales of 50,000 copies in 1833, its first year of publication.

Harrison appears to have understood the power of attractive colour images as a marketing tool to inspire readers to purchase his magazine, and the new plants he showcased. The dahlias in the coloured plates are accomplished artworks, portraying the flowers with accuracy and with a slightly naïve quality in the diagrammatic stylisation of the flowers. The ‘Picta Perfecta’ dahlia, praised in The Floricultural Cabinet for its perfectly round form and spectacular colours, was in fact a seeding raised by Harrison.

Harrison was meticulous in recording the names of prize winning dahlias as well as those of the judges and entrants. From his records, certain grower’s names re-appear, such as Mr Pamplin, a florist who lived in Islington, and raised the beautiful golden yellow dahlia ‘Pamplin’s Bloomsbury’ which was illustrated in the magazine.

Joseph Harrison (1798 – 1856) was born in Sheffield where his father worked as head gardener at nearby Wortley Hall, a position Joseph took over in 1828. He left Wortley Hall in 1837, setting up as a florist in Downham, Norfolk and eventually moving to Richmond, Surrey. As well as The Floricultural Cabinet, Harrison also edited The Gardener’s Record.

While they are an important part of our horticultural history, flower shows are by their nature ephemeral events. The plants, the exhibitors, and in some cases, even the venues where the shows took place are now long gone, but they live on in Harrison’s vivid descriptions.

Here follow extracts from The Floricultural Cabinet of three contrasting dahlia shows, documented by Harrison during his country wide tour of 1835. They start with the East London Dahlia Show, a small and well established local event with sixty stands of flowers on display. At the opposite end of the scale, Harrison is clearly captivated by The Bath Royal Flora and Horticultural Society’s Grand Annual Dahlia Show. Its decorations included an extraordinary figure of a Mexican chief made out of dahlias, to celebrate the country where the plant originated. But later in the season, Bath is topped by The Cambridge Florists’ Society Dahlia Show, with its model of a hot air balloon constructed out of 2,300 dahlia blooms and arranged around a chandelier:

The East London Dahlia Show

‘This exhibition took place, as usual, at the Bakers’ Arms, Hackney-road, and was well attended. Sixty stands of flowers were placed in competition, and the judges, Messrs, Alexander, Catleugh, and Glenny, placed them as follow :—

Stands of Twelve Blooms.—1, Mr. Dandy; 2, Mr. Crowder; 3, Mr. Rowlett; 4, Mr. Wade; 5, Mr. James; .6, Mr. Turner; 7, Mr. Dunn; 8, Mr. Williams; 9, Mr. Brown; 10, Mr. Riley; 11, Mr. Sharp; 12, Mr. Hogarth; 13, Mr. Green; 14, Mr. Buckmaster.

Stands of Six Blooms.—1, Mr. Williams; 2, Mr. Thornhill; 3,My. Dandy; 4, Mr. Crowder; 5, Mr, Wade; 6, Mr, Hogarth; 7, Mr, Dunn; 8, Mr, Carp

Sadly this pub that once stood at the corner of Warner Place and Hackney Road is now demolished.

The Bath Royal Flora and Horticultural Society’s Grand Annual Dahlia Show

‘The committee made extraordinary exertions to render this show the most splendid and attractive of the whole season, and they fully realized their purpose. The first object which met the view was a most singular figure on the right-hand lawn: it was that of a Mexican chief, holding a basket of flowers; the whole figure was composed of Dahlias, which, as our readers well know, came originally from that country ; and difficult as the task must have been, even the features of the countenance were very ingeniously delineated. This figure exhibited no less than 150 varieties of the Dahlia, in every imaginable tint, and of every gradation of size. A little beyond was the figure of a tree of considerable size, the trunk and every branch being composed of Dahlias of an equal number of varieties, and in the colour and size of the flowers.’

The Cambridge Florists’ Society

‘This Society had their grand Autumnal Show of Dahlias on Thursday, Sept. 24th, in the Assembly room at the Hoop Hotel. We have witnessed many floral exhibitions here and at other places, but we never before beheld any thing approaching the beauty and magnificence of this exhibition; on no previous occasion was the Dahlia exhibited in so high a state of excellence. We may expect to see great additions made to the colours and varieties of this very beautiful flower, but we much doubt if ever the grand stand of prize flowers displayed on this occasion will be surpassed in size or quality by that of any future show. The task of decorating the room was entrusted to Mr. Edward Catling, florist, of Cambridge; and nothing could possibly exceed the happy and elegant taste with which every ornament was executed. The sides and ends of the room were beautifully decorated with evergreens, wreaths, and Dahlias. At the head of the grand stand was an immense orange tree thickly studded with Dahlias, to represent the fruit in its various stages of growth, backed by a beautiful Fuchsia multiflora, 12 feet high, from the Botanic Garden. At the end of the room, was a prettily variegated crown entirely composed of Dahlias. But the grand attraction of all was a splendid balloon, wholly formed of Dahlia-blooms, suspended from the ceiling, the car of which appeared to be illuminated, from being placed over a gas chandelier. This ariel machine had a striking effect, the flowers being arranged in stripes to represent variegated silk; and we were told that more than 2,300 Dahlias were required to complete the balloon, exclusive of the car, from which two flags were pendent.—The afternoon show was attended by a numerous and respectable company; but the evening exhibition was crowded beyond all former precedent, owing to its being on the eve of the horse-fair, which gave the neighbouring country people an opportunity of witnessing the finest display of Dahlias ever seen in Cambridge. Upwards of 700 well-dressed persons were in the room at one time, and from eight to half-past nine o’clock the number amounted to little, if any, short of 3,000 persons, all with happy countenances, highly delighted with the fairy scene ; added to which were the musical strains of the Cambridge Military Band, who played several new and difficult pieces, with a precision and taste that would have done credit to veteran performers. After the ladies had withdrawn, more than 200 members and their friends sat down, with the splendid flowers before them, and enjoyed the scene with music, song, and toast. Fifteen new members were elected, and we rejoice to learn that the Society meets with the well-merited support of all classes.’

Further details and links below – the dahlia illustrations are taken from various issues of The Floricultural Cabinet across the 1830s.

Levick’s Beauty of Sheffield

The Floricultural Cabinet

Brown’s Royal Adelaide

The Floricultural Cabinet

Harris’s Acme of Perfection

The Floricultural Cabinet

Harris’s Inimitable Dahlia

The Floricultural Cabinet

Dodd’s Mary

The Floricultural Cabinet

Barratt’s Vicar of Wakefield

The Floricultural Cabinet

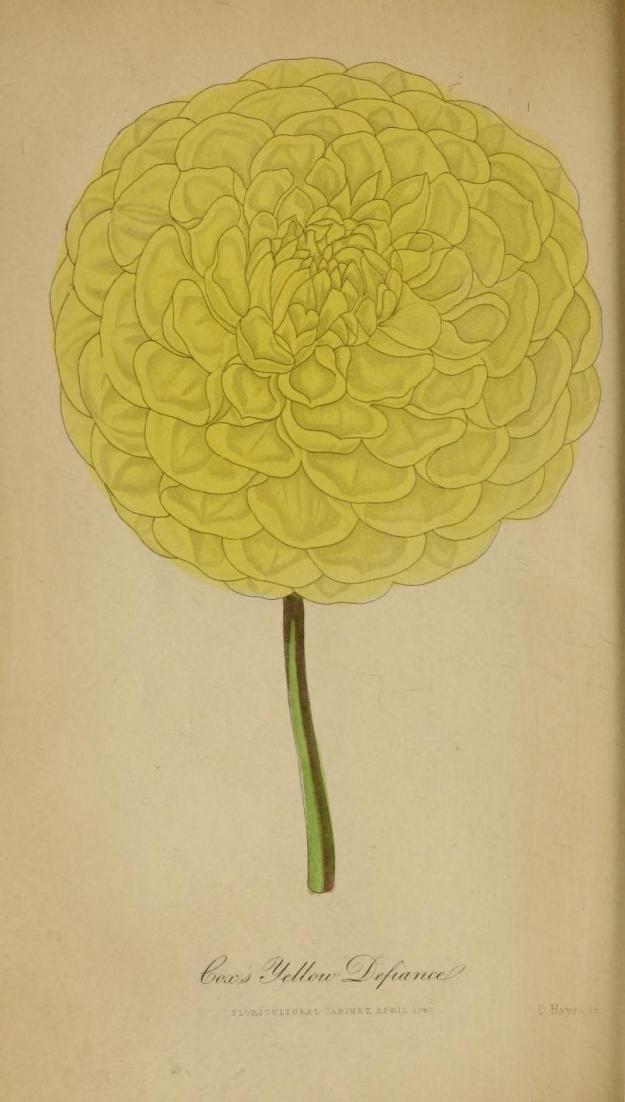

Cox’s Yellow Defiance

The Floricultural Cabinet

Pamplin’s Bloomsbury

The Floricultural Cabinet

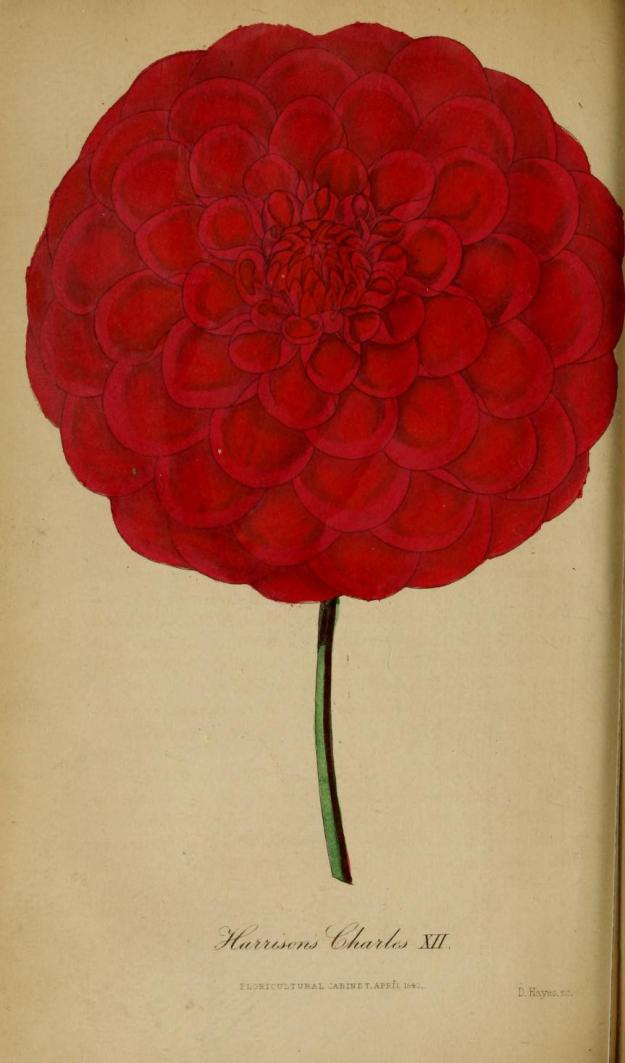

Harrison’s Charles XII

The Floricultural Cabinet

Further reading:

The Floricultural Cabinet and Florist’s Magazine

Vol 3 1835 from the Natural History Museum’s Collection here

Joseph Harrison Wikipedia here

There’s a chapter about florists and the passion for growing all types of flowers for show in The Gardens of the British Working Class by Margaret Willes published by Yale University Press here