Front gate at Restoration House, Rochester

Back in September, I paid a visit to Restoration House, a remarkable house and garden located in Rochester, Kent. Originally two buildings of medieval origin, these were combined in the late 16th or early 17th century to create a city mansion house. Restoration House takes its name from a visit King Charles II made on the eve of his restoration to the throne in May 1660. But this name also seems singularly appropriate to its current owners, Johnathan Wilmot and Robert Tucker, who’ve cared for the house since 1994 and restored it with sensitivity and meticulous attention to historical detail.

On the day we visited, we were greeted by an enthusiastic band of local volunteers who invigilate the rooms open to the public, and welcome guests. Moving through the house, a combination of plain waxed floorboards, wood panelling and limewashed walls produces a softness in the light, and a sense of calm, forming a perfect setting for the owners’ extensive collections of elegant period furniture, paintings and sculpture.

(As this house is also a home, it’s not usually permitted to take photographs, but for anyone curious to learn more about the story of Restoration House, and see images of its interiors, there are links to the website and to an excellent feature at the Bible of British Taste below).

Outside, the gardens are a continuation of the owners’ skill in choosing and arranging beautiful plants, objects and materials to create a series of contrasting spaces. Working with the considerable challenges of the site, with frequent changes of level and tall walls that enclose and divide the garden, some areas are relaxed and intimate, inviting one or two people to linger and enjoy a view, while others like the impressive box parterre and the Renaissance garden have a more formal atmosphere. Two gardeners maintain these gardens to an exceptionally high standard.

Front view, Restoration House, Rochester

Back view of Restoration House with lawn mown diagonally creating a diamond pattern

As well as historical planting, the garden full of brightly coloured salvias, enjoying the early autumn sunshine

The Renaissance garden which incorporates a section of Tudor wall

Passing through the garden, one of the delights is the tiny kitchen garden. Bordered by an open structure made of wooden poles and trellis supporting espaliered apple trees, the square space is divided by narrow brick paths. Asparagus is grown here, together with flowers for the house. On one corner, an antique iron gate adds to the rustic feel.

The kitchen garden is enclosed with an open structure made of wooden poles and trellis work

Inside the kitchen garden where fruit, vegetables and flowers are grown

Handmade wooden trellis

Espaliered apple with wooden ladder and tools. The trug is one of the few plastic items we saw in the garden

A fine ironwork gate in the kitchen garden

Two charming greenhouses, both constructed using salvaged glass and frames, contain collections of pelargoniums in terracotta pots and tropical plants as well as various galvanised watering cans.

Greenhouse made out of various salvaged materials

Leaded windows in another greenhouse

A variety of materials are used for paving and pathways in the garden from stone flags, to brick and granite setts. Some of the setts form mini stepping stones to prevent too much wear in areas of lawn which receive high volumes of traffic from visitors.

Herringbone brickwork pathway

Setts

Setts sunk into the lawn

Wooden structure supporting clematis and steps leading to another section of the garden

There’s an abundance of statuary in the garden, and one of my favourite pieces was this young man, placed amongst the cold frames and a collection of planted containers. Elsewhere, a kneeling ram on an ornate stone plinth is placed against the dark green backdrop of some yew topiary, and makes a pleasing contrast to the functional plainness of a garden bench nearby.

Statue of a young man with cold frames and pot arrangement

Sculpture of a kneeling ram with garden seat

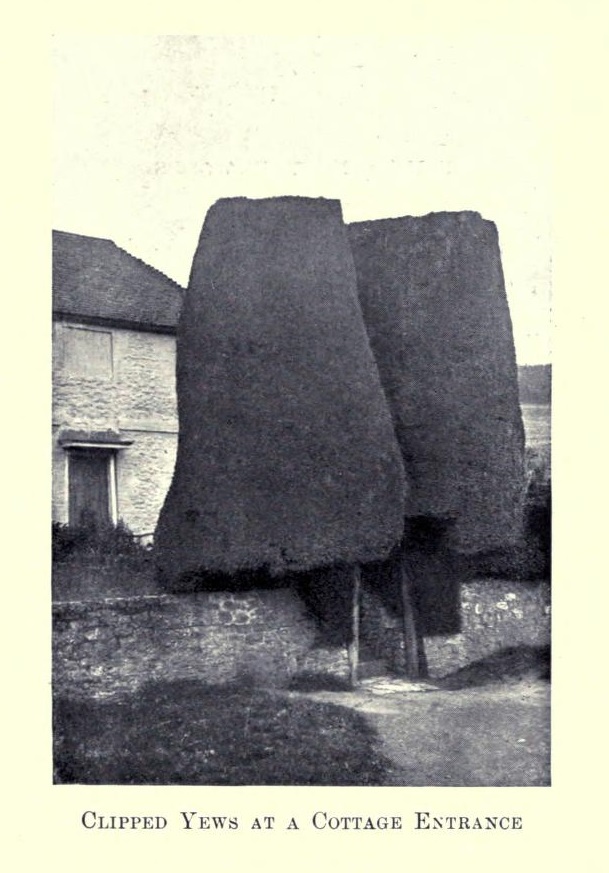

The garden is full of topiary, much of it carefully clipped into bottle shapes. These strong forms are a theme in the garden and help to create a sense of unity between the various spaces. Here, two matching trees frame the entrance to a lower part of the garden, their formal shapes contrasting with the spreading branches of an enormous quince tree. Topiary seems to possess the ability to look at home in every garden, whatever its size.

Yew topiary with quince tree beyond

Twin containers framing a doorway to the house

Many of the plants in the garden like box, lavender, sage, mulberry, quince, medlar and apple trees would have been familiar in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. When we visited, lavender and sweet woodruff were being used as strewing herbs in the toilets. This custom dates back to medieval times, where fragrant herbs were placed on floors so that people walking on them would release their sweet smelling fragrances. Although the concept of strewing herbs was familiar to me, this was the first time I’d experienced the actual effect, which brought this element of social history vividly to life.

The garden also includes plants that were introduced to England later, such as dahlias and salvias, which have become popular in recent years, valued for their intense colours and long flowering season. Inside, Restoration House is full of flowers cut from the garden.

A mulberry tree dominates this bed, close to the kitchen garden

Quince

Fruitful lemon tree in a terracotta container

Thanks to Johnathan Wilmot and Robert Tucker for sharing this special and atmospheric place. On their website, there’s much more about the history of the building and the battle to acquire the land on which the Renaissance garden now stands. Restoration House and Gardens are open on Thursdays and Fridays from June to September – see below for more details.

Further reading:

Restoration House website here

Views of the interiors of Restoration House from the Bible of British Taste here

Strewing herbs on Wikipedia here